Sof Drashes

Gut Yontif – Yom Kippur Drash

October 1, 2021

By Alex Golub

The High Holy Days are a time of teshuvah. Between the beginning of Rosh Hashanah and the end of Yom Kippur we hope to have improved. And yet, there is a puzzle: Why do the people we read about on this holiday seem to get worse, not better? On Rosh Hashanah, we read of Abraham’s sacrifice of Isaac. At the end of Yom Kippur we read Jonah. This placement suggests that Jonah is somehow an improvement on Abraham. But could it really be that Jonah is a better role model for us than Abraham? Let us examine the matter more closely.

At first, Jonah does not strike us as a model of spiritual growth. When God calls on Abraham, Abraham answers the call and prepares to make the ultimate sacrifice — the death of his son. When God calls Jonah, Jonah runs away! In Jonah, there are people who unthinkingly obey God’s commands in the same way that Abraham does — but they are the goyim, not Jonah! When Jonah’s ship is beset with storms, it is the sailors who are eager to placate God, not Jonah. And when Jonah reveals God’s prophecy to Nineveh, the king obeys faster, and more readily, than Jonah ever does. As one commenter points out, in Nineveh even the donkeys are better at teshuvah than Jonah!

The solution to the problem is this: The High Holy Days do take us on a journey of moral development. It is a journey from the moral simplicity to moral nuance. Abraham may bargain with God over lives at Sodom and Gomorah, but on Rosh Hashanah his faith is simple, unquestioning, and un-nuanced. The Jonah of Yom Kippur, on the other hand, is pious, complicated, and wily. He’s been around the block. His journey inside the fish has been extensively drashed by commenters.

Jonah helps the whale confront the apocalyptic beast it will meet at the end of time, as if he were Dr. Who. The fish takes him underground to the foundations of the temple of Jerusalem, where Korach’s family are davening. He is shown the path on the floor of the sea that Moses and the Israelites walked across. Just as Jonah goes on a journey in the fish’s belly, we too go on a journey on Yom Kippur. In fact, one side effect of Yom Kippur is that you feel as if you are inside a fish all day long. Like Jonah, we look forward to having a shower at the end of our spiritual journey.

Jonah helps the whale confront the apocalyptic beast it will meet at the end of time, as if he were Dr. Who. The fish takes him underground to the foundations of the temple of Jerusalem, where Korach’s family are davening. He is shown the path on the floor of the sea that Moses and the Israelites walked across. Just as Jonah goes on a journey in the fish’s belly, we too go on a journey on Yom Kippur. In fact, one side effect of Yom Kippur is that you feel as if you are inside a fish all day long. Like Jonah, we look forward to having a shower at the end of our spiritual journey.

On Rosh Hashanah, we are taught moral simplicity. It is a necessary lesson because, remarkably, we often know what the right thing to do is. We just don’t want to do it, because doing the right thing is often not easy or comfortable. On Yom Kippur, we are reminded of moral complexity. It is a necessary lesson because, remarkably, it’s often hard to know what the right thing to do is. We just tell ourselves we have an easy answer, because living with complexity is not easy or comfortable.

There is nothing easier than knowing that you are totally right, and other people are totally wrong. Just look at our politics today. There are right-wingers beating police on the head with flags (or, I should say, the flag poles) who claim to be patriots who believe Blue Lives Matter. There are left-wingers who believe Black lives matter but want the police defunded, as if that will make the lives in our neighborhood more secure! When someone beats a cop over the head with an American flag, does that mean that patriotism is criminal? When someone loots a store because they believe in human rights, does that mean human rights are wrong? No. It means simplicity is bad. The problem is not symbols or slogans. The problem is simplicity. We are not facing a battle between Democrats and Republicans, we are facing a battle between simplicity and nuance.

We need the moral clarity of Abraham. But let’s be honest, this clarity has the moral texture of a smoothie. Ok I shouldn’t have said that. I’m sure we could all use a smoothie right about now. We must grow from there to a place of moral complexity. We must learn the skills that Jonah has: We must learn to look around. To wonder what the other options are. To ask ourselves if there isn’t a better way. To ask what simplicity will cost us, and others. And we must never forget the one thing that Jonah knows from the beginning: his enemies, the Ninevites, have the capacity to change for the better, and they will do so when given the opportunity.

We need the moral clarity of Abraham. But let’s be honest, this clarity has the moral texture of a smoothie. Ok I shouldn’t have said that. I’m sure we could all use a smoothie right about now. We must grow from there to a place of moral complexity. We must learn the skills that Jonah has: We must learn to look around. To wonder what the other options are. To ask ourselves if there isn’t a better way. To ask what simplicity will cost us, and others. And we must never forget the one thing that Jonah knows from the beginning: his enemies, the Ninevites, have the capacity to change for the better, and they will do so when given the opportunity.

This Yom Kippur, Jonah chooses not to take the easy way out. Rather than doing what he is told, he choses a much longer and much riskier path. In 5782, may we be like him. Gmar chatimah tova.

Breathe: Yom Kippur 2021 Drash

September 29, 2021

By Alan Kosansky

On Yom Kippur, we read from the Machzor, “what we do this day can change our lives.” What we do from this moment until the shofar blows tomorrow night can change our lives.

This year, as last year, we are a Congregation. But we cannot congregate. The air we share may kill one of the dear friends amongst us. The simple and divine act of breathing has become a risk to our survival. It has created previously unimaginable obstacles to how we connect, how we congregate, and how we share each other’s lives. Our challenge in the coming year is how do we stay healthy and safe AND connected. How do we protect our lives and how do we imbue them with meaning through our connection to others? I believe we can answer this question if we take a few moments, both now and each day, to focus on our breath…both as the source of fears in these times of Covid, and even more so as the essence of our spiritual and physical connection to one another.

So let me share with you 5 thoughts on breath.

One, our breath connects us physically and spiritually to one another. Both in the moment, and across the centuries of time. A few years ago, in a Rosh Hashanah drash, Alex encouraged us to continue a centuries-long dialog amongst the generations of Jews that connects us to those who came before us and those who will follow us. This dialog has a physical component to it as well: Astrophysicist Ethan Siegel explains that in every breath we take, every inhale and word spoken, we breath in a portion of the exact same air that our ancestors breathed, and exhale atoms that our descendants will breathe for generations to come. Every single breath we take, connects us physically to our entire history, and our entire future. If we take a moment to notice this amazing scientific fact, then it connects us spiritually as well.

Two, we use our breath to inspire with word, song and sound. The shofar blast on Rosh Hashanah and the end of Yom Kippur is simply the sound of our breath, consolidated, stretched and transformed into sound, so that we can hear in our soul the miracle of our breathing. Story-telling is another powerful form for this dialog.

When the great Rabbi Israel Baal Shem-Tov

Saw misfortune threatening the Jews

It was his custom

To go into a certain part of the forest to meditate.

There he would light a fire,

Say a special prayer,

And the miracle would be accomplished,

the misfortune averted.

Later when his disciple,

The celebrated Magid of Mezritch,

Has occasion, for the same reason,

To intercede with heaven,

He would go to the same place in the forest

And say: “Master of the Universe, listen!

I do not know how to light the fire,

But I am still able to say the prayer.”

And again the miracle would be accomplished.

Still later,

Rabbi Moshe-Leib of Sasov,

Would go into the forest and say:

“I do not know how to light the fire,

I do not know the prayer,

But I know the place

And this must be sufficient.”

It was sufficient and the miracle was accomplished.

Then it fell to Rabbi Israel of Rizhyn

Sitting in his armchair, his head in his hands,

He spoke to God: “I am unable to light the fire

And I do not know the prayer;

I cannot even find the place in the forest.

All I can do is to tell the story,

And this must be sufficient.”

And it was sufficient.

Three, Kol ha’olam kulo

Gesher tzar me’od

Veha’ikar lo lifached k’lal.

The whole world

Is just a narrow bridge

and the main thing is to have no fear at all

I still remember vividly the first night of Aviva, my eldest daughter’s, life. We arrived home after a long day of Pam birthing Aviva. We lay Aviva down in a basinet next to our bed and Pam promptly fell asleep from the exhaustion of the birthing experience. I lay in the still of the night, listening to each and every breath of my new daughter, she still being less than 24 hours old. I was scared. I was scared that if I was not awake to confirm each breath, how could I be sure that she would still be breathing in the morning when we awoke. It was the most significant act of faith I have ever taken to allow myself to fall asleep, and trust that Aviva would continue to breathe through the night.

In these times of Covid, living cautiously but not in fear, sometimes takes an act of faith.

[Pause]

Our first breaths are at birth, our last breaths at death. In 2012 my dad had a stroke and then 3 days later a massive stroke that left him alive only because of the ventilator that enabled him to breathe. My sister and brother and I made the hard decision to remove him from the ventilator. The doctors informed us that he would then only breathe for 20 minutes or so. My first inclination was that I did not need to be present in the room for my Dad’s dying breath. However, on further reflection I remembered the ethos of my family and my Jewish community: life is about showing up, about being present for both the big and the small moments in each other’s lives. So my sister and brother and I sat with my father as each breath became thinner and more labored, and finally the last breath passed through his lips.

A Fourth reflection on breath: while we meditate on the miracle of breath, we would do well to also remember the too many in our country who have said “I cannot breathe” as their last living word before their death. For many in our country, this has been the story of the past two years as much as Covid. Hearing the personal stories of black parents coaching their teenage children how to be extra cautious during routine traffic stops has been eye-opening, if not heart-breaking. The parallelism between this story and the covid story is striking: there is a very thin line between that which sustains and protects us and that which threatens us.

If we are to transform our own lives, we can only succeed by doing our part to transform the society in which we live. Everyone’s breath is equally miraculous, every breath matters.

Lastly, five: you may consider starting each day with the following mediation from the morning blessings: Elohai neshamah shenatata bi tehorah hi. “My God, the soul, the breath, the neshamah that you have placed within me is pure”

Rabbi Zalman Schachter-Shalomi writes: “Our minds might insist that we go directly to the Infinite when we think of God, but the heart doesn’t want the Infinite; it wants a You it can confide in and take comfort in.” Amidst the jagged and often wrenching complexities of daily life, what a balm it can be to feel the Presence as close as my breath.

[Pause]

A hasidic tale tells of the disciple who asked his rabbi the meaning of community one evening when they were all sitting around a fireplace. The rabbi sat in silence while the fire died down to a pile of glowing coals. Then he got up and took one coal out from the pile and set it apart on the stone hearth. Its fire and warmth soon died out.

[Pause]

This day of Yom Kippur is a small replica of our life. We hunger for that which we deny ourselves. We think there is a well-planned script for what we are to do, but as the day passes, we realize we are improvising and working on intuition. The final closing of the gates at the end of Neilah seems very far away, yet it will be upon us and gone in what will seem like no more than a breath.

This past 18 months of a covid-19 world is yet another reminder that there is a very thin line between that which sustains us and that which threatens us.

May the next 24 hours, and the year ahead, be the beginning of a journey for you. A journey on which, in each breath, you experience more awe than fear, more connection than separation, and may you burn brightly and warmly with those near to you.

Gmar Hatima Tova.

Drash for Ki Tavo 5781

September 29, 2021

By Gregg Kinkley

Sometimes, being assigned a drash rather than waiting for one you intentionally select ends up being a boon rather than a burden. That was certainly the case here. I had two preconceptions about this important parashah that I found were both wrong upon closer examination:

- Beginning of the End. I considered Ki Tavo just another parashah in Devarim that was in no other way remarkable except for containing the infamous Tokhekha (the curses). Instead, I find that it is the important beginning of the end of Moses’ narrative to Am Yisrael, his final charge to the people as they enter the Promised Land.

- House Without a Ki. I had lumped Ki Tavo in with Ki Teitzei (which immediately precedes it) as just another parashah full of “ki’s”. I find instead that Ki Tavo is not like other “Ki’s”: whereas in Ki Teitzei many paragraphs begin with that multivalent conjunction “ki,” Ki Tavo importantly begins with V’hayah ki tavo; “and it will be WHEN (not IF) you come into the land that HaShem has given you…”. The conclusion that you will enter the Land is already implicit: it is rather time to prepare for what must be done now that the Land will be occupied.

Many a drash has focused on the unusual or unexpected use of motion verbs in Hebrew (e.g., just two parashiyot hence, Vayelekh Moshe stresses Moses’ distancing himself from the people; in Lekh Lkha, the concept of going from the known to the unknown is alluded to). Here in Ki Tavo, we may ask why a verb of motion indicating direction towards the speaker (“to come”) is used, when Moses is pointedly being left behind and will not join his Instructed People in the Land. The sense of the verb Tavo here is not just “come” but “enter to reside”; an intentional change of state on the part of the addressed, an immersion. The phrase Ki Tavo therefore is not describing action from the point of view of the speaker, but rather from the vantage and psychological state of the referent: the people.

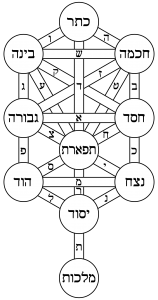

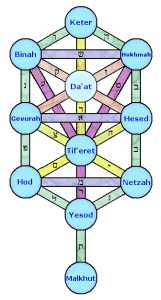

My approach to this discussion of Ki Tavo, in an attempt not only to elucidate but also to unify my remarks, will be to follow the old rabbinic method of exegesis known by the acronym PaRDeS (“paradise”): Pshat (surface meaning); Remez (metaphorical allusion); Drash (moralistic commentary); and Sod (deep or esoteric meaning).

Pshat: a list of what happens in this parashah

- Bikkurim: law of first fruits (with its verbal formula)

- Maaser: law of tithes (with its verbal formula)

- Exchange of vows (People to HaShem; HaShem to People)

- Torah chiseled on rock coated with plaster

- Chorus of Warnings with Stereo Amens from Gerizim and Eival

- List of Blessings (Good Results)

- List of Curses (Bad Results)

- Summary

On the Pshat level we are only looking at themes, at actions, at the continuity of the text/story. Although some interesting things are happening, they do not all appear extrinsically related. For those connections we need to search further, deeper.

Remez: the wedding

Given the rather cut-and-dried ordering of the contents of this entire parashah, the individual elements, both in their substance and their order, may at first appear arbitrary and rambling. On deeper reflection, one can begin to discern a familiar pattern – a remez or allusion to a sanctification, a kiddushin: a wedding between HaShem and His People.

1: Bikkurim, or the law of first fruits, is about humanity recognizing what HaShem has given us: that which we planted was given to us by Him, and not earned from our own efforts alone. The ceremonial verbal formula accompanying the bikkurim offering stresses our humble beginnings (“my father was a wandering Aramean”) and how we were snatched from this bootless, itinerant fate to become land-owning, crop-cultivating stewards of the Land through His mercy. This then is what the Groom brings to the marriage: the bride price, expressed as an obligation between God and Man.

2: Maaser, or the law of the tithe, is set forth to remind us of the duties between and among the people: not only to the priestly class, but also to the widow and orphan. It too is accompanied by a verbal formula, an affidavit of sorts, making the declarer swear that he has kept HaShem’s laws and not forgotten to give what must be given, do what must be done. Since this is of fiscal benefit to the people and society as a whole, this is an allusion to the money the bride brings with her into the union with HaShem – the dowery.

- The exchange of vows found in Devarim 26:17 – 18:

[17] You have avouched ( (האמרתthe Lord this day to be your God, and that you would walk in His ways, and keep His statutes, and His commandments, and His ordinances, and hearken to His voice. [18] And the Lord has avouched you ( (האמירךthis day to be His own treasure, as He has promised you, and that you should keep all His commandments.

How very much like the exchange of vows at a wedding this reads: “I take thee, HaShem, to be my God; and I take thee, Israel, to my treasured people.” Here the partition between the pshat narrative and the remez seems to fade away, the meaning of the words being so striking and fraught.

- When the text moves immediately on to describe a rock coated with plaster upon which the Torah is to be engraved, it seems that the conversation has indeed shifted dramatically – but in the world of remez this is but the next logical step: the lithic Torah stands as an eternal ketubah given by HaShem to his people, the seal of the sanctification. The laws and duties expressed therein protect the people and offer an eternal blessing.

- The chorus of warnings (“arur”) enunciated by the Levi’im, accompanied by the rest of Israel intoning a choral “amen,” reminds one of a typical wedding scenario where the officiant charges the couple with the rules and expectations of the parties in that holy estate, while the crowd of well-wishers, onlookers, and family all participate in praise and approval. And even though the text involved here is a selection of very negative things, the subject matter is relevant to marriage: laws of authority within the estate (man/God, parent/child, therefore man-wife – forgive the unintentional sexism implicit here); laws of sexual purity and taboos; laws of respect for property not one’s own (as two enter from an individual existence into a true partnership).

- The list of blessings that occur right after the “arurs” represents the Sheva’ Berachot of the wedding ceremony – quite a few more than seven to be sure, but the allusion is palpable.

Seen as an allusion to a holy union with HaShem, the topics and ordering of this parashah now fall into place.

Drash: Sotah 35b

In this delightful sugya in the Talmud, R. Yehudah and R. Shimon, perennial opponents when it comes to arguing dikduk from Torah, consider the purport and consequences of the exact words of the Torah where it is commanded that the people engrave the words of Torah on the rock covered with plaster:

ת״ר כיצד כתבו ישראל את התורה רבי יהודה אומר על גבי אבנים כתבוה שנאמר וכתבת על האבנים את כל דברי התורה הזאת וגו׳ ואחר כך סדו אותן בסיד אמר לו רבי שמעון לדבריך היאך למדו אומות של אותו הזמן תורה אמר לו בינה יתירה נתן בהם הקב״ה ושיגרו נוטירין שלהן וקילפו את הסיד והשיאוה

“The Rabbis taught in a baraisa: How did Israel inscribe the Torah? Rabbi Yehudah says they inscribed it on the stones, as it is stated: and you shall inscribe on the stones all the words of this Torah, and afterwards they coated them with plaster. Rabbi Shimon said to him: according to your words, how did the nations of that time learn Torah? (the inscription was covered up by the plaster according to R. Yehudah) Rabbi Yehudah replied: The Holy One Blessed be He endowed them with an extra measure of insight and they sent their scribes who peeled off the plaster and carried it away (i.e., a plaster cast copy in reverse of the inscription).”

From just these few verses of Torah, the Rabbis picked a fight over what seemed to them a contradiction in the literal reading of the process for incising the Torah on the rocks: is the chiseling to be done on the rocks directly, so that the plaster would be applied over the rock after the chiseling, obscuring the words of Torah, or do we cover the rock first with plaster and then chisel through the plaster?

The exegetical significance of this little extract centers around what it means to publish the Torah, to whom it is published, and by what means. Do we hide the Torah from the Nations, or are we commanded to spread it? And if we are to spread it, how? Rabbi Yehudah’s clever solution to Rabbi Shimon’s query (which, note, implies that he already expects it to be the duty of Jews to teach (or at least publish) Torah to the Nations, as he is concerned how that will happen if the words are plastered over) is that the Nations peel off the plaster, leaving in their hands what amounts to a reverse carbon copy, a plaster cast, of the Torah which they can “carry away” (assumedly to study). On an exegetical level, we then see that the Torah is to be given to the Nations, but separated from the Rock (i.e., HaShem, its direct Source) and given indirectly (printing from reverse image). The people Israel, on the other hand, have the original and the relationship with the Author: we have what is revealed and what is hidden!

Sod: the deeper structure of the parashah

Dichotomous revelation. We have seen at the beginning of this parashah that the laws of bikkurim are given, followed by an oral formula. The laws of maaser are then given, also with a corresponding oral formula.

The dichotomies here are salient:

- dues owed to HaShem (bikkurim) versus dues owed to Man (maaser to the priestly class, and alms to the poor on the third year of maaser).

- the need for an oral component (the formula) to the written requirement for both taxes.

- the dichotomy of the written law (Torah in plaster) and the oral expression of it (the Amen chorus on the Mounts).

This appears to be using staged elements to represent the trademark Jewish approach to divine law: a Written Law as explained and implemented by an Oral law. The template for the system that would be laid down in the Mishnah and Gemara are hinted at right here in the structure of the enunciation of the laws of Ki Tavo.

The Chorus of Arurs. When the Levites announced the specialized Arurs to the people arrayed on Mounts Gerizim and Eival, (along with the people’s amen), they were phrased as curses, but they were substantively nothing less than lo taasehs or negative commandments. This reminds us of the giving of the Ten Commandments at Sinai (another marriage metaphor for the Jewish people), but this time, in this telling, there are twelve commandments (the number of the tribes represented on the Mounts) rather than ten; they are told by the priestly class (God’s sheliach or agent on Earth) rather than HaShem Himself; and they are all negative commandments, rather than only half of them so.

Below is a list summarizing the general content of each of the twelve arurs into five categories, with the corresponding or relevant number of the Ten Commandments after each:

The Arurim:

- Authority: man to God, children to parent (#2, #5)

- Justice system for haves and have nots (#3, #9)

- Sex taboos (#7, #10)

- Two types of murder: secret and for hire (#6, #8)

- The seal: follow this law and be bound by it (#1)

| 1 | I am the Lord thy God |

| 2 | Thou shalt have no other gods before me |

| 2 | Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image |

| 3 | Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain |

| 4 | Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy |

| 5 | Honour thy father and thy mother |

| 6 | Thou shalt not murder |

| 7 | Thou shalt not commit adultery |

| 8 | Thou shalt not steal (understood as kidnapping) |

| 9 | Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour |

| 10 | Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s house |

| 10 | Thou shalt not covet thy neighbour’s wife |

| 10 | or his slaves, or his animals, or anything of thy neighbour |

The Blessings and the Curses. It is important to note that these blessings and curses read like consequences, not like laws (unlike the arurs on the Mounts that precede them). “If you follow all these commandments, then… (the blessings); but if you do not follow these commandments, then… (the curses).”

This manner of pronouncement reveals HaShem’s Laws not as criminal and civil laws of Man (“don’t do that;” “do that”) but rather as acts and their consequences as Laws of Nature (imagine the Law of Gravity being stated as Don’t float rather than If you let go of an object then it will fall).

Why so much repetition here? Why must every consequence be stated twice and in a positive/negative format? This is responsive to the halakhic requirement for the administration of the legal system on the people: no one can be held liable for the commission of an act that is the subject of a negative commandment unless he or she is (1) made to realize at that moment that the contemplated behavior is proscribed and (2) made aware of what the punishment will be should he or she commit the act. Having now fulfilled this requirement through the blessings and curses, the Law is now made binding on all the people through this form of mass publication.

The vows. The He’amars (“caused or made to say”: “spoken for”; “avouched”) Note the curious syntax of the two verses where the exchange of vows between HaShem and the People is made:

Et Adonai he’emarta hayom You avow the Lord today …

V’adonai he’emirkha hayom And the Lord avows you today…

The first vow, made by the people, has a syntax one would expect to find only in Klingon (!): Object, Verb, Subject; while the vow HaShem makes to the people has the expected order, at least by English standards, of Subject, Verb, Object. While Biblical Hebrew is often analyzed as “verb initial,” and without getting into secular scientific arguments of Chomskyan underlying structure, I think it fair to say that the first vow stands out as unusual, inasmuch as it begins with the grammatical particle signaling a definite direct object – not one’s first choice for beginning a sentence, irrespective of matters of stress. On the level of Sod, this could stand as a reminder that HaShem is always first, even when we perceive ourselves as the actor: He is always the Prime Cause.

And let us say, Amein.

בס״ד

Drasha Ki Teitzei

September 1, 2021

By R Daniel Lev

Like a number of rabbinically-inspired parshiot, this one will take a circuitous route from the first pasuk / sentence through a number of apparently unrelated ideas until it finally lands right back to the pasuk itself and provides a new meaning for it. And on top of that, we may end with a theme from the coming High Holidays.

Like a number of rabbinically-inspired parshiot, this one will take a circuitous route from the first pasuk / sentence through a number of apparently unrelated ideas until it finally lands right back to the pasuk itself and provides a new meaning for it. And on top of that, we may end with a theme from the coming High Holidays.

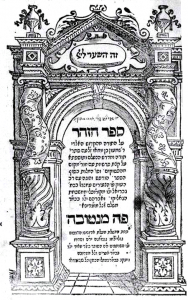

The teaching I want to share with you today comes from Rabbi Kalonymos Kalmish Shapira who lived in early 20th century Poland and died on November 3, 1943 in the Trawniki concentration camp. Some say he was the last new Rebbe in eastern Europe. He is best known as the Piazetsna Rebbe, named after the Warsaw suburb where he lived and provided care for children and other community members. Before he was taken to the concentration camp, he was able to have his writings buried in a large milk canister which was found after the war.

The Rebbe commented on the first pasuk of the Torah portion in Deuteronomy 21:10 that says: “When you go out to war against your enemies, and HASHEM delivers them into your hands, and you take them captive…”

כִּי-תֵצֵא לַמִּלְחָמָה, עַל-אֹיְבֶיךָ; וּנְתָנוֹ יְיָ אֱלֹהֶיךָ, בְּיָדֶךָ–וְשָׁבִיתָ שִׁבְיוֹ

Ignoring in this sentence the themes of war and triumph, the Piazetsna Rebbe brings up the idea of Chesed meaning Infinite Love. He offers a teaching from the second-generation Chassidic leader, Reb Dov Ber, the Maggid of Mezrich, who quoted Psalm 110:4 that says, “You are a priest forever” – Ata Kohein Le-Olam.

The Maggid taught that the word for priest, Kohein, is the attribute of Chesed, Infinite Love. This notion probably comes from a midrash describing Aaron the Priest as a loving guy who served the community from the depths of his heart. In light of this, the Maggid re-translates the verse as saying, “You are Infinite Love forever.” From this we can understand why the Men of the Great Assembly, a semi-legendary body of priests, prophets, scholars and other leaders constructed many of the prayers we have today to include the formula: Baruch Atah… ”Blessed are You…”

The Maggid taught that the word for priest, Kohein, is the attribute of Chesed, Infinite Love. This notion probably comes from a midrash describing Aaron the Priest as a loving guy who served the community from the depths of his heart. In light of this, the Maggid re-translates the verse as saying, “You are Infinite Love forever.” From this we can understand why the Men of the Great Assembly, a semi-legendary body of priests, prophets, scholars and other leaders constructed many of the prayers we have today to include the formula: Baruch Atah… ”Blessed are You…”

These leaders offered this in order to bring us closer to the “You” who is Infinite Love. What is this “love?” Or, for that matter, what does it mean to “love G-d” or that “G-d is Infinite Love?” On the most intimate level it means connection. I’m sure you don’t feel connected to your loved ones because they look a certain way, are rich or give you things. What love is for most of us is a connection with our beloveds. Similarly, the Men of the Great Assembly wanted us to feel closely connected to HaShem – so they invited us to address the Divine as “You.”

In doing this they shifted us away from the third person relationship we had with the Biblical-period G-d, such as, “He is Loving and Jealous.” Now, the closer relationship we have allows us to experience the Chesed / Infinite Love of the Divine Presence. As Rabbi Kalonymos Kalmish of Piazetsna said: “When we utter the blessing, ‘Blessed are you HaShem our G-d…,’ surely G-d is truly facing us.”

In doing this they shifted us away from the third person relationship we had with the Biblical-period G-d, such as, “He is Loving and Jealous.” Now, the closer relationship we have allows us to experience the Chesed / Infinite Love of the Divine Presence. As Rabbi Kalonymos Kalmish of Piazetsna said: “When we utter the blessing, ‘Blessed are you HaShem our G-d…,’ surely G-d is truly facing us.”

The Rebbe further differentiates our relationship with the Holy One by labeling the third person approach as Nistar, or hidden. We can also understand the more personal second person, “You,” relationship as meaning Nigla, or revealed. The Piazetsner said that at Mount Sinai, HaShem gave all of us the Torah as a community; it was Nistar, in the third person. However, the Torah teaching that is specific to each of us individually is hidden within the whole Torah given to the community. Though I received the general Torah like everybody else, my personal piece of Torah is usually inaccessible. However, when I am in more direct relationship with HaShem – by addressing Her as “You” (in the second person) – then the Nigla happens, my individual Torah is revealed.

The Piazetsna Rebbe expresses this by saying: “Although HaShem Teaches Torah to the entire Jewish people, this is not a teaching that is personal and individual to each person…so it is up to each of us to work to achieve that level where the (Infinite Presence) speaks to you individually.”

So how do we do that? The rabbi’s answer is simple: “through Prayer. By saying ‘You’ to HaShem a person achieves a revelation of G-d…He speaks directly to you…teaching you your individual Torah, directly and immediately. G-d says ‘you’ to the individual in return. When this happens, you can see and comprehend a part of the Torah that is uniquely yours…

I’d add that this can also occur at times when we are not formally praying. We do it when we bring the consciousness and awareness that imbues our prayers into other moments of the day.

OK – now for the moment we’ve all been waiting for: The Rebbe is about to directly comment on our Torah verse. Here it is again: “When you go out to war against your enemies, and HASHEM delivers them into your hands, וְשָׁבִיתָ שִׁבְיוֹ – and you take them captive…”

First of all, there is a long rabbinic tradition of re-imagining the “enemies” spoken of in this pasuk, and in the Torah in general, as representing our own inner struggles with harmful habits, destructive emotions or confusing thoughts. This has been further developed by Jews in the Musar ethical movement and those who hold Chassidic mystical perspectives. This pasuk invites us to do what we can to defeat these inner enemies.

Next, the Piazetsner Rebbe comments on the end of the pasuk that says: “…so that you will take captives.” – וְשָׁבִיתָ שִׁבְיוֹ – Literally, you could read that Hebrew phrase as “You’ll captivate the captives.” But the Rebbe doesn’t read the meaning as coming from the Hebrew root-word, SHAVA – to capture. Instead, he reads it as SHUV – to return or restore – they both have somewhat similar letters. The Hebrew root word for return is related to TESHUVA – which can be translated as “turning your life around” from the misguided directions that do not serve us well. It is a foundational practice that we engage in during the High Holidays and beyond.

Next, the Piazetsner Rebbe comments on the end of the pasuk that says: “…so that you will take captives.” – וְשָׁבִיתָ שִׁבְיוֹ – Literally, you could read that Hebrew phrase as “You’ll captivate the captives.” But the Rebbe doesn’t read the meaning as coming from the Hebrew root-word, SHAVA – to capture. Instead, he reads it as SHUV – to return or restore – they both have somewhat similar letters. The Hebrew root word for return is related to TESHUVA – which can be translated as “turning your life around” from the misguided directions that do not serve us well. It is a foundational practice that we engage in during the High Holidays and beyond.

The Rebbe underscores this by translating the captives phrase into: “You will restore his restoration…’ He then goes on to cite other supportive Torahs: “And in the book of Aycha / Lamentations (5:21), the Jewish people say, ‘Restore us to You, and we will be restored’ – or “Return us to you and we will be restored” –

הֲשִׁיבֵנוּ יְיָ אֵלֶיךָ וְנָשׁוּבָה

The Rebbe continues: “And HaShem answers in Malachi 3:7 with ’Return to Me and I will return to you.” And apropos of Martin Buber’s philosophy of “I and Thou,” when we address HaShem as “You,” from a personal, heart-felt place during prayer, or at any moment, we can experience a return to the Source who will draw us back to Him even more closely.

I’d like to bless you, and please bless me back, that as we approach this coming Rosh HaShanah we should all receive our own, personal Torahs by taking a moment to talk with the Holy Presence. And that each of us, in our own way, will return to a higher level of who we are on the inside – to return to a better version of ourselves. Shabbat Shalom.

Drash for ʻEikev

By Sandra Z Armstrong

August 27, 2021

I once had a dream that my 90 year old friend, Mr. David Goodman was teaching me that living a Jewish life meant choosing from a whole array of desserts like the Viennese table of scrumptious options to satisfy all your cravings. I looked over to see the table of delicious options and Mr. Goodman said choose any of these options, each one will be wonderful and go do them. Mr. Goodman was a Torah scholar who read for our synagogue Temple Israel in NJ every Shabbat.

When he came down from the bimah after Torah reading, he often had tears in his eyes from the passion and emotion of the Torah. He reminded me a lot of Rabbi Morris Goldfarb.

I sat with Mr. Goodman every week and every Shabbat he taught me how to be Jewish by just observing him. Then there was Ziggy (he and Betty were both Holocaust survivors), Harry Grant very British with a bowler hat each week, Gerald Schraub, Marvin Amsterdam, Howard Schreiber, Steve Ehrlich and Lou Messulam. It was a small Shabbat minyan that I loved very much and I knew it wouldn’t last much longer as they would eventually move far away to retirement places or pass on. I took on the membership campaign as a mitzvah because I saw that we would be losing something more precious than gold. We would be losing our steady minyan to read Torah. At the very end of Mr. Goodman’s life, I visited him in his assisted living apartment. He showed me the items of the most importance to him. The framed picture of his Temple Israel Tribute for the many, many passionate years that he read Torah, showed us the way to mitzvot and lived a Jewish life. Included in his prized possessions were his tefillin and weathered prayer book.

We all have models set before us of Yiddishkeit of people who taught us how to be good Jews. ʻEikev is the quintessential love song of a leader, Moses knowing that he would not make it to the promised land but forever until his last breath loving God and Torah. The Israelites were new people with a slave mentality and needed a tremendous amount of help and guidance in knowing HaShem’s ways.

We all have models set before us of Yiddishkeit of people who taught us how to be good Jews. ʻEikev is the quintessential love song of a leader, Moses knowing that he would not make it to the promised land but forever until his last breath loving God and Torah. The Israelites were new people with a slave mentality and needed a tremendous amount of help and guidance in knowing HaShem’s ways.

In our adult lifetimes, I am sure that each of us, even if we were not raised with all our mitzvot to follow, we had strong Jewish models of the direction to follow. We had guidance on how to keep what we find sacred to God and ourselves. And that my friends is the meaning of Congregation Sof Ma’arav. For we have faced many challenges in the last 18 months to keep Shabbat, to keep reading Torah, to honor our tradition and to do good under the eyes of HaShem. Our initial struggles with Zoom and not seeing each other in person were overcome for the love of this community. In the last 2 months when we went to a hybrid and in person service we took every possible care to follow the commandment of making Shabbat a holy experience for those faraway and also those of us here in this room today. Many hours, many ideas, thoughts, passion and feelings went into all these preparations.

Yet our rewards were great, we celebrated Shabbat with an incredible almost surprising amount of joy, whether we were just on Zoom or in a combined Zoom in person service. We never, ever will take for granted the ability to come together in a physical space and take out a Torah to read from the bimah. We have clung to the commandments in the best of possible ways. So I ask you, would Moshe Rebeinu, the greatest of our leaders, would Moshe be proud of us?

In ʻEikev and the book of Devarim, Moshe takes the creation story of a people and explains it to us in simple language. If you look at the reading for ʻEikev in the Torah, it is basic, simple, complete, like an arrow, his words come directly to our hearts. Other parashot in the Torah have new words, hidden values, and we search out the meanings. Not so for ʻEikev, as Moshe uses simple understandable repetitive words to recount the story of the birth of the Israelites into a strong people of faith. As HaShem created and gave birth to the world, so too does Moshe continue this creation story. He was born and designated to create the nation of Israel.

Our tradition teaches us to look back and to look forward almost simultaneously. Our own Biblical Hebrew language is who we are. For what other language other than Hebrew, in the very structure of their verbs of action “asa,” to do, to make, can flip back and forth between past and future within each action. We at Sof Ma’arav look back to keep and find joy in our beautiful community. The word for they kept is “shamru” they guarded Sof in the past. V’shamru they will guard Sof into the future. The “vav” consecutive links our Biblical past into our future days.

Moshe taught us HaShem’s words that man cannot live by bread alone. With food and being satiated, you go from one meal to the next. Trying to fill up on that enjoyment of the moment. When in reality, with community, mitzvot and love of Torah you are “full up” all the time and especially when celebrating Shabbat together.

Moshe taught us HaShem’s words that man cannot live by bread alone. With food and being satiated, you go from one meal to the next. Trying to fill up on that enjoyment of the moment. When in reality, with community, mitzvot and love of Torah you are “full up” all the time and especially when celebrating Shabbat together.

God warns us to never become complacent through Moshe’s words. When we prosper and are living a “good life” then we need to remember how we were created and why. To live a full life, a good life on earth reflected in heaven is to do “asa” mitzvot and never forget that we are humans, sometimes a little higher than animals. Our wants, needs and desires must be directed like an arrow toward heaven at all times.

Drash on Va-Etchanan

August 27, 2021

By Don Armstrong

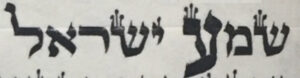

Devarim, the fifth and last moshianic book of the Pentetuch, lays the foundation for the monotheism of modern Judaism by highlighting the supremacy of Adonai. In the preface to Devarim on page 980 of Etz Hayim, Jeffrey Tigay notes that today’s parsha is, ”the most clear advocate of monotheism and the ardent, exclusive loyalty that Hashem’s chosen people owe to their loving, just and transcendent God.”

Commentators on today’s parsha, “Va-Etchanan,” emphasize that, despite its small size, Israel has an obligation to be a light unto all the nations of Hashem’s world. Moshe stresses Hashem’s covenant with the patriarchs that was affirmed at Mt. Sinai, Mt. Horeb and in Israel’s travels in the wilderness and which is reaffirmed when Israel enters the promised land.

The book of Devarim anticipates Israel’s enjoyment of Hashem’s bounty in the promised land, but this bounty and Israel’s welfare are conditioned upon maintaining a society that is governed by Hashem’s social and religious laws. These laws are Hashem’s gift to Israel; their observance secures the mutual closeness and love between them. The Torah’s humanitarianism is most developed in Devarim by emphasizing the ideas of social justice and Tikun Olam, with concern for the welfare of the poor and our duty to repair and maintain Hashem’s creation.

Devarim urges every Israelite to study and understand Hashem’s laws. It explains the meaning of events and the purpose of Hashem’s laws to obtain Israel’s willing, informed consent. Devarim also has strongly influenced later Jewish tradition. The core of Jewish practice is the daily recitation of the Sh’ma and the public reading of the Torah. Also based on Devarim are the duties to bless Hashem after meals, say Kiddush on Shabbat, affix mezuzot to door posts, wear tefillin and tzitzit, perform acts of charity for the poor and much more. Devarim’s impact on Jewish life cannot be overstated. No idea has shaped Jewish history more than monotheism, and no verse has shaped Jewish theology, consciousness, and identity more than the Sh’ma.

In researching my drash, I studied the “Va-Etchanan” drashes prepared over the last decade by Rabbi Jonathan Sacks, of blessed memory. So what is the Sh’ma? Rabbi Sacks said that it is the supreme testimony of Jewish faith. He noted that two ancient civilizations that shaped Western culture were very different in their respective world views: the ancient Greeks were masters of the visual arts (art, sculpture, architecture and theater), a sight-based culture of the eye. Ancient Jews, as a profound religious principle, were not.

Hashem, the focus of ancient Jewish culture and worship, is invisible. Hashem could be heard, but not seen. Thus, ancient Jewish culture was an oral culture of the ear. Despite the fact that Torah, the law of the Jewish people, has 613 commandments, Rabbi Sacks noted the astonishing fact that Biblical Hebrew had no verb for to obey. This affects our entire understanding of Judaism because it shows that despite our focus on the divine commandments, ours is not a faith that values blind, unthinking obedience. Instead, Hashem wants us to understand why the commandments were made so that we can develop a moral conscience. What Hashem wants us to do is not irrational or arbitrary; it is for each Jew’s welfare, the Jewish people’s welfare, and ultimately the welfare of all humanity.

Rabbi Sacks also focused on a brief passage buried amidst the epic portions of today’s parsha that has large implications for our moral life in Judaism: “You shall diligently keep the commandments of the Lord your God, and his testimonies and his statutes, which he has commanded you. And you shall do what is right and good in the sight of the Lord, that it may go well with you…”. What is meant by the right and the good that is not already covered in the preceding verse? Rashi says it means that one should not adhere strictly to the letter of the law because the moral life may require one to compromise his rights or go beyond his duties under the law to produce a just result. Ramban agreed with Rashi but he went further saying that, “even where Hashem has commanded you, do what is good and right in his eyes, for Hashem loves the good and the right.”

Rabbi Sacks also focused on a brief passage buried amidst the epic portions of today’s parsha that has large implications for our moral life in Judaism: “You shall diligently keep the commandments of the Lord your God, and his testimonies and his statutes, which he has commanded you. And you shall do what is right and good in the sight of the Lord, that it may go well with you…”. What is meant by the right and the good that is not already covered in the preceding verse? Rashi says it means that one should not adhere strictly to the letter of the law because the moral life may require one to compromise his rights or go beyond his duties under the law to produce a just result. Ramban agreed with Rashi but he went further saying that, “even where Hashem has commanded you, do what is good and right in his eyes, for Hashem loves the good and the right.”

Ultimately this reflects the tension between the two great principles of Judaic ethics: justice and love. Justice is universal. It treats all people alike, rich and poor, the powerful and the powerless, making no distinctions based on color or class. But love is particular. A man loves his wife and parents love their children for what makes each of them unique. The moral life combines both aspects and this is why moral decisions cannot be reduced solely to universal laws. This is why the Torah speaks of the “right and the good” over and above its commandments, statutes and testimonies.

I conclude my drash with a paraphrase of the beautiful words of Rabbi Sacks in his Covenant and Conversation written in 2007:

In the silence of the desert the Israelites were able to hear the word of Hashem. And one trained in the art of listening can hear not only the voice of Hashem but also the silent cries of the lonely, the distressed, the afflicted, the poor, the needy, the neglected and the unheard. For speech is the most important of all gestures, and listening is the most human and divine of all gifts. Hashem listens and asks us to listen. That is why the greatest of all commands, the one we read in today’s services, the first Jewish words we teach our children, the last words of Jewish martyrs as they went to their deaths, are the words of the Sh’ma. It is Moshe’s command to Israel to listen and learn from Hashem and teach this wisdom to our children.

As we did earlier in our service today when we recited the Sh’ma, we covered our eyes to shut out the world of sight so that we could more fully enter the spiritual world of sound, not the world of Hashem’s creation but Hashem’s spiritual world of revelation. But if we create an open, attentive silence in our soul, we can hear Hashem’s still, small voice of love and revelation.

I pray that in today’s troubled and disquieting times, each of us takes the time each day to listen to Hashem’s voice and find comfort and solace in his direction and love.

Shabbat Shalom

Parashah Pinchas – Zelophehad’s Daughters

August 1, 2021

Drash by Robert Littman

The Torah is the sacred story of the Jewish people for a period of our first 500-600 years, from our origins with Abraham to the death of Moses. It is a sacred story because it relates the interaction of God and history. The Torah contains a narrative, and woven into the narrative a law code, ranging from basic, almost universal laws of civilization, that is the Ten Commandments received by Moses on Mount Sinai, to mundane regulations such as separation of mixed fibers, and inheritance laws.

The Torah is the sacred story of the Jewish people for a period of our first 500-600 years, from our origins with Abraham to the death of Moses. It is a sacred story because it relates the interaction of God and history. The Torah contains a narrative, and woven into the narrative a law code, ranging from basic, almost universal laws of civilization, that is the Ten Commandments received by Moses on Mount Sinai, to mundane regulations such as separation of mixed fibers, and inheritance laws.

The fundamentalist view of the Torah is “Torah from Sinai,” which sees the Torah as a document dictated to God on Sinai: “This is the Torah that Moses put before the people of Israel, from the mouth of God by the hand of Moses” (Numbers 9:23).

Modern analysis of the text has shown that the Torah contains material from many periods and the text we now have reached its present form by the end of the 7th century BCE, though smaller additions and changes continued on until the text was finalized in the last centuries of the first millennium BCE. Minor changes continued until the complete fixation of the text in the 6th – 10th century CE by the Masoretes. For example, Goliath in the Hebrew texts of the Dead Sea Scrolls and Septuagint (Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible) was 4 ½ cubits (6 ft. 9 in.), versus 6 ½ cubits (9 ft. 9 in.) of the Masoretes.

The story of Zelophehad’s Daughters relates to inheritance, particularly of land. While semi-Nomadic tribes like the B’nei Yisrael had inheritance of moveable property and wealth (as is the case among modern Bedouins), the description of inheritance seems to relate to land ownership and a period when the Israelites had settled in Israel. The laws set up for Zelophehad’s daughters represent inheritance of a settled land. The story in the Torah acts as the theological justification for the legal rights of inheritance that were practiced in ancient Israel.

The story of Zelophehad’s Daughters relates to inheritance, particularly of land. While semi-Nomadic tribes like the B’nei Yisrael had inheritance of moveable property and wealth (as is the case among modern Bedouins), the description of inheritance seems to relate to land ownership and a period when the Israelites had settled in Israel. The laws set up for Zelophehad’s daughters represent inheritance of a settled land. The story in the Torah acts as the theological justification for the legal rights of inheritance that were practiced in ancient Israel.

Many commentators throughout the ages have held Zelophehad’s daughters and their inheritance rights as some extraordinarily modern recognition of women’s rights. In fact, nothing could be further from the reality. The ancient Israelites organized their society as a patrilineal, patrilocal kinship group. Membership was assigned based on descent from a common male ancestor.

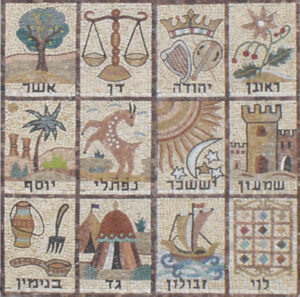

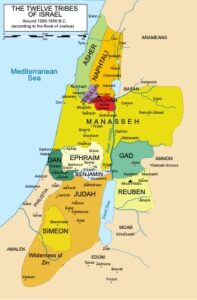

The Israelites were formed into 12 tribes. These tribes were a kinship based group, where membership was conferred on those who descended from one of the children of Jacob. This kinship group, called the shevet or matteh, meaning tribe, had smaller patrilineal kinship groups, the mishpachah (extended family) and beth-av (immediate family).

One of the overriding principles of the kinship group was the maintenance of the land within the family, and a strong prohibition against alienation of the land from the kinship group. A man would bequeath his land to his sons. However, what happens if he dies without sons, only daughters or no heirs. In the case of no heirs, the land would pass to his nearest patrilineal relative – father, brothers – or their patrilineal descendants. In the case of daughters, the daughters were married off to their nearest patrilineal relative, usually patrilineal first cousins.

The land would then pass to the husband of the daughter, and thus remain in the patrilineal lineage of the beth-av. This also was a means of providing assurance that daughters would share in the benefits of their father’s property. This system of inheritance was almost identical to that practiced by other ancient patrilineal societies, such as the Greeks and the Romans. It was not unique to ancient Israel.

The land would then pass to the husband of the daughter, and thus remain in the patrilineal lineage of the beth-av. This also was a means of providing assurance that daughters would share in the benefits of their father’s property. This system of inheritance was almost identical to that practiced by other ancient patrilineal societies, such as the Greeks and the Romans. It was not unique to ancient Israel.

Sacred narratives thus are used to reinforce societal practices. How then do we react to the societal practices in the Torah that differ from our own? Today, in most of the world, women can inherit in the own right, and we follow this practice even in modern Israel. The Torah tells us to stone homosexuals. We no longer do this, nor many other laws of Numbers and Leviticus. How do we pick and choose what laws we do follow? That is a issue that Jews have struggled with for the last 1500 years. The answers are not simple, and the debate will continue as long as there are Jews.

Balak-Balʻaam Drash

August 1, 2021

By Marlene Booth

I’ve been thinking about storytelling a lot lately, about why we tell the stories we do, about who tells those stories, and about what we can learn by shifting the point of view of the storyteller. And the parshah of Balak is a perfect place to begin. Why, for starters, is there a story about a talking donkey? Why does this story appear here in Ba’midbar in the midst of the Israelites still wandering in the desert and kvetching to Moshe for more food, more water, and, with Korah and his followers, more power? Who is telling the story in Balak? What difference does that make?

A donkey showing his teeth and braying.

Just to refresh your memory, in this week’s parsha, Balak, King of Moab, is afraid that the Israelites will attack his nation. He asks help from the pagan prophet, Balʻaam, to come to his nation and curse Israel. God does not allow Balʻaam to go but then he lets him go as long as Balʻaam prophesies only what God commands. So Balʻaam goes with Balak’s emissaries, riding on his trusted donkey. But 3 times en route, the donkey sees an angel with a drawn sword blocking the way and the donkey prevents Balʻaam from moving forward. Each time, Balʻaam beats his donkey. After the third time, the donkey speaks to Balʻaam, protesting his beatings and pleading her case as an always loyal donkey. In that moment, the angel the donkey has seen finally appears to Balʻaam and makes clear to him that if the donkey had not stopped moving, the angel would have killed Balʻaam. Nonetheless the angel allows Balʻaam to go to Balak but only to say words that God puts in his mouth. So Balʻaam goes to to do Balak’s bidding but all of Balʻaam’s curses toward Israel turn to blessings, including the famous poem we read at shachait, “ma tova ohalecha yaacov,” “how beautiful are your tents Jacob, your dwellings Israel. Blessed are they who bless you.” Balʻaam goes so far as to promise that the Israelites will triumph over their enemies, including Moab.

So, in this parshah, we have a talking, sensible donkey who sees more than her master can see, a pagan prophet who, though a pagan, blesses Israel and predicts the triumph of the Israelites—what’s going on here? Why is this story included in Ba’midbar, sandwiched between parshat chukat that deals with Moses’ sister Miriam dying, Moses’ brother Aaron dying, and Moses being punished for his anger in striking a rock by not being allowed to enter the Promised Land, and next week’s parshat Pinchas in which a census is taken, the daughters of Zelophechad plead for and gain their rights of inheritance, and Moses’ successor, Joshua, is named? Those parshiot seem on one level at least to deal with the founding generation passing on, a new person assuming leadership, rights of inheritance established, and the story set to continue in the Promised Land with a new generation. Parshat Balak proceeds as if untouched by the story of the wandering Israelites.

So, in this parshah, we have a talking, sensible donkey who sees more than her master can see, a pagan prophet who, though a pagan, blesses Israel and predicts the triumph of the Israelites—what’s going on here? Why is this story included in Ba’midbar, sandwiched between parshat chukat that deals with Moses’ sister Miriam dying, Moses’ brother Aaron dying, and Moses being punished for his anger in striking a rock by not being allowed to enter the Promised Land, and next week’s parshat Pinchas in which a census is taken, the daughters of Zelophechad plead for and gain their rights of inheritance, and Moses’ successor, Joshua, is named? Those parshiot seem on one level at least to deal with the founding generation passing on, a new person assuming leadership, rights of inheritance established, and the story set to continue in the Promised Land with a new generation. Parshat Balak proceeds as if untouched by the story of the wandering Israelites.

One possible explanation for Parshat Balak comes from storytelling. Who is telling the story? Whose perspective are we hearing? In Balak, we move away from the Israelites being the central characters and we see one part of the story of their wanderings not from their POV (or the omniscient narrator’s POV with the Israelites being the central actors) but from the POV of their enemies. What are they thinking about the Israelites? The scene of the action shifts, we leave the Israelites behind for a moment, and we see how others, in this case Balak, king of Moab, perceive them. Outsiders are beginning to fear the power of the God who protects the Israelites. Even a pagan prophet like Balʻaam listens to God and his angel and succumbs to God’s intervention. No less a scholar than Nechama Leibowitz argues that the pagan Balʻaam ultimately “gives himself up to the divine prophetic urge.”

Parshat Balak seems to be in BaMidbar not to move along our narrative but to interrupt it. Perhaps in the midst of establishing succession in Israel and showing repeated complaints and rebellions among the Israelites, the Torah wants us to take a breath, stop the action, and consider the scope of God’s influence, specifically from the point of view of outsiders. It is as if the Torah is saying, “nu, stop kvetching for a moment and look at what even our enemies say about God.” If God can turn curses into blessings, maybe we will make it to the Promised Land despite ourselves. Maybe Balʻaam and our talking donkey have much to teach us about seeing what’s in the road ahead and about listening, even when complaining is much more fun.

Shabbat Parashat Matot-Masei 5781

July 29, 2021

By Dina Yoshimi

Rosh Chodesh Menachem Av

Parashat Matot opens (BaMidbar 30:3) with God’s commandments regarding the making of vows to H”S (אִישׁ֩ כִּֽי־יִדֹּ֨ר נֶ֜דֶר לַֽיהֹוָ֗ה) and the taking of oaths imposing an obligation on oneself (אֽוֹ־הִשָּׁ֤בַע שְׁבֻעָה֙ לֶאְסֹ֤ר אִסָּר֙ עַל־נַפְשׁ֔וֹ).

BaMidbar, Chapter 30, verse 3 begins: אִישׁ֩ כִּֽי֨ a man who (makes a vow, etc.)…

BaMidbar, Chapter 30, verse 4 begins: וְאִשָּׁ֕ה כִּֽי and a woman who (makes a vow, etc.)…

Verse 3 addresses all concerns regarding a man who undertakes a vow or an oath; all matters regarding a man are accounted for in a single verse.

As for a woman, the matter begins in verse 4, and continues on until verse 16 (BaMidbar 30:4-16), addressing the various circumstances that may apply in the case of אִשָּׁ֕ה כִּֽי, a woman who makes a vow, etc.

What can I say? Women are complicated!

The text addresses when a woman’s vow or oath stands, and when it may be annulled; and, while the very fact that a woman’s vow or oath may – under certain circumstances – be annulled by her father or by her husband may send readers down the path of condemning “the traditional patriarchal society” or protesting “the treatment of women as property”, both of these purported “readings” of the text completely ignore what is actually written, to wit, that there are different laws regarding the taking of a vow or the swearing of an oath for men and women:

אִישׁ֩ כִּֽי֨ a man who (makes a vow, etc.)…

אִשָּׁ֕ה כִּֽי a woman who (makes a vow, etc.)…

NOT אִישׁ֩ כִּֽי֨ where the laws are only for men and there are NO laws for women because women cannot make vows to H”S or swear sacred oaths; and

NOT אִישׁ֩ כִּֽי֨ and we have to wait for the Rabbis to explain whether אִישׁ here only refers to men, or whether it refers to men and women alike.

No, it’s as clear as day: The Torah is telling us that there can be different laws for men and women, and, most importantly, that women can make vows and swear oaths.

Perhaps the most well-known example of a woman making a vow to H”S comes from the very opening of I Shmuel; the story comprises the haftarah we read on the first day of Rosh HaShanah, the story of Hannah. The story relates how Hannah, married to Elkanah, was childless while his second wife, Peninah, had given birth to his children. While on their annual pilgrimage to Shiloh to make an offering to H”S, Hannah is overcome with מָ֣רַת נָ֑פֶשׁ (marat nefesh ‘bitterness of heart/soul’) – she is inconsolable, even after her husband assures her of his unconditional love, whether she bears him children or not.

In the depths of her despair, pouring out prayers to H”S through her tears, she makes a vow (I Shmuel 1:11, וַתִּדֹּ֨ר נֶ֜דֶר): If H”S will grant her a son, she will dedicate him as a nazir to the service of H”S.

A married woman, in emotional turmoil, bordering on existential distress, vows to dedicate a child – the offspring of a mother and a father – and a male child, no less — the potential inheritor of the family name and inheritance –, without consulting the husband and father-to-be. If ever there was a vow to be annulled by a husband, this would be it.

And yet, when Hannah finally gets around to sharing this vow with her husband, after the child already has been born and named, her husband’s response is unpaternalistic, unpatriarchal, and unauthoritative. He says, עֲשִׂ֧י הַטּ֣וֹב בְּעֵינַ֗יִךְ “Do what is good in your eyes.” (I Shmuel 1:23) – not quite the image of woman as a downtrodden, dominated, powerless piece of property that some would read in the plain sense of the text.

This pushback against ascribing a male dominant, patriarchal system to ancient Israel resonates with the work of Dr. Carol Myers, Professor Emerita of Religious Studies at Duke University. Myers, in her 2013 Presidential Address to the Society of Biblical Literature (‘Was Ancient Israel a Patriarchal Society?’, Journal of Biblical Literature, 133(1), 2014) provides archaeological and textual evidence to argue that, “In the aggregate, [tasks undertaken by women in Ancient Israel] likely required more technological skill than did [those undertaken by men].” (p. 21) She cites anthropologist Jack Goody’s comment that, “…because women could transform the raw into the cooked and produce other essential commodities, they were seen as having the ability to ‘work … wonders.’” (p. 21).

Annul my vow at your peril, o spouse of mine!

But seriously – the point Myers aims to make is that, rather than seeing Biblical text as presenting us with a male-dominating-female society that has no place for women’s independence or voice, we would do better to conceptualize a society where “female–male relationships are marked by interdependence or mutual dependence” such that “…for many—but not all—household processes in ancient Israel, the marital union would have been a partnership.” (pp 21-22, emphasis added)

Aaah, the marital union…this phrase from Myers resonates with the closing verse of the section on vows in our parashah (BaMidbar 30:17):

אֵ֣לֶּה הַֽחֻקִּ֗ים אֲשֶׁ֨ר צִוָּ֤ה יְהֹוָה֙ אֶת־מֹשֶׁ֔ה בֵּ֥ין אִ֖ישׁ לְאִשְׁתּ֑וֹ בֵּֽין־אָ֣ב לְבִתּ֔וֹ בִּנְעֻרֶ֖יהָ בֵּ֥ית אָבִֽיהָ׃

These are the chukim (the decrees) that H”S commanded Moses, between a man and his wife, and between a father and his daughter in her youth, in her father’s house.

The mitzvot of Torah are often identified as falling into two categories: bein adam l’Makom (between a person and H”S) and bein adam l’chavero (between a person and his/her fellow); but here, this closing verse teaches us to see that there are other sacred relationships that must be recognized, valued and protected — relationships that form the very fabric of our family units, relationships that are as old as Creation itself.

The first and primary relationship is that between husband and wife. Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz reminds us (Biblical Images: Men and Women of the Book, p. 5) of the Talmudic teaching that “Adam and Eve came into being as a single creature with two faces or sides – the one, male; the other, female…woman was created from Adam’s tsela [a word that can mean “rib” or “side”] because she was to begin with a tsela, or a side or aspect of [adam ha-rishon] primordial man, who thus came to be two distinct persons.” R. Steinsaltz continues, “The upshot is that the relationship between men and women…has the character of the quest for something lost…male and female are essentially parts of a single whole, originally created as one being…”

As for the relationship of parent to child, Steinsaltz (ibid., p. 6) argues that procreation “is a secondary function [of the male-female relationship]…the birth of a child is a kind of bonus, a new creation…wondrously brought into being by the very act of reunification.”

These sacred relationships then are primordial and mysterious, they are the stuff of ongoing acts of creation – leaving (the house of one’s father) and cleaving (to one’s spouse). Perhaps it is no surprise that the laws regarding these relationships בֵּ֥ין אִ֖ישׁ לְאִשְׁתּ֑וֹ בֵּֽין־אָ֣ב לְבִתּ֔וֹ (bein ish l’ishto, bein av l’vito, between a man and his wife, and between a father and his daughter) are presented as חֻקִּ֗ים (chukim, decrees), that is, those decrees that transcend rational reason, that we are not meant to fully understand.

Thus, even as the Torah sets out with an appeal to our rational sensibilities – what could be more natural than differentiating rules for men from those for women? – this closing verse אֵ֣לֶּה הַֽחֻקִּ֗ים אֲשֶׁ֨ר צִוָּ֤ה יְהֹוָה֙ אֶת־מֹשֶׁ֔ה (eileh hachukim asher tzivah H”S et Moshe…) teaches us to challenge our expectations and question our assumptions; and, rather than accepting division and dominance, push ourselves to see, to learn, and to understand that we are inevitably bound up in relationships of oneness, of reconnecting with something lost, a wholeness we can only regain by seeing ourselves as tzela, as sides that seek to reconnect with each other.

Shabbat Shalom!

Drash—Shabbat Hazon

July 28, 2021

Special Guest Drash by Rabbi Natan Margalit, son of Fran Margulies

ציון במשפט תפדה ושביה בצדקה Zion shall be redeemed with judgement and those that return to her with righteousness.

Why the repeat? If Zion is redeemed, don’t we already know that those that return to her will also be redeemed?

So asks the Piaseczner Rebbe, Rabbi Kalonymous Kalman Shapiro. He is most famous for being the Hasidic Rebbe of the Warsaw Ghetto. His sermons from the time of the war are preserved in a book called Esh Koshesh, the Holy Fire. It was buried in a metal canister and hidden when he knew that he, too, would be taken out of the ghetto. He was brought to a the Trawniki work camp where he was part of a group of Jews, both secular and religious, who formed a mutual aid pact with one another. He swore that he would not accept a path to freedom without the whole group being free. And indeed, the underground came in a tunnel and offered, begged him to escape with them to freedom and life. But he had made a bond and an oath to the whole group. He was killed in the massacre of all the Jews in the Trawniki camp on November 3, 1943.

It wasn’t only his sermons from the ghetto that were buried in that metal canister. It was his whole life’s work. He had one published book that had come out before the war—on education of younger children, Chovot HaTalmidim—and it had established his reputation as a leader in progressive religious education at the time. But the rest of his life’s work including the book that I am citing now, Derekh HaMelekh, was buried in that canister.

So, coming back to our Haftorah, what exactly was the rebuke that Isaiah was giving Israel? They were doing all the rituals but it made God sick. It wasn’t just that they were hypocrites—they didn’t believe what they were saying in their prayers—but it was their actions which spoke louder than words. Violence, lies and theft were the actions of these supposedly pious worshippers.

The destruction has to do with their actions, and if we are to learn from this Haftorah, our actions as well. But looking deeper—what was it about those actions that were so wrong? They were self-centered. They ignored the good of others for their own gain; they trod on the dignity of the poor, they cheated the orphan and the widow, they profited from violence and lies. They put themselves at the center.

In his commentary on Shabbat Hazon, the Piaseczner writes about the importance of our actions, and how actions and thoughts are intertwined.

He is writing this commentary in 1936. As the leader of his Hasidic community, he feels the need to help his followers keep their faith strong even as they see very little evidence of God’s justice and mercy. Quite the opposite, they see evidence all around of evil seeming to be rewarded and the good being punished. He describes how even in people who want to believe that God is just and loving, thoughts of doubt can come into their minds. Even though they want to keep their faith strong, eventually these thoughts will wear it down, just as dripping water will eventually wear down a stone.

He asks: How can one avoid this almost inevitable weakening of faith through stray thoughts?

He answers: It depends on how much we put ourselves, even our thoughts, at the center?

He says if we put ourselves at the center in our day-to-day actions: when we want to sleep, we sleep, when we want something, we take it—then we’ll also be at the mercy of our own wandering thoughts because in our actions we’ve put ourselves at the center of our lives. The only way to not be at the mercy of our stray thoughts, and to keep ourselves solid in trust, he says, is to get in the habit of acting for others, giving of ourselves to serve others will reorient our sense of self and help us from putting ourselves at the center.

It reminds me of the Buddhist meditation bumper sticker I’ve seen: “Don’t believe everything you think.” When we center our sense of Being beyond our personal selves, we gain perspective and strength to not listen to all our stray thoughts.

When we do Tzedakah, he says, we give of ourselves. Not only do we help others, but we also reorient our own being, decentering ourselves and putting our energies into the larger whole.

So, he comes back to our verse from Isaiah: ציון במשפט תפדה ושביה בצדקה “Zion will be redeemed with justice, those that return to her with Tzedakah.” But שביה, “those that return to her,” can also be translated, “those that have gone backwards”. So, he interprets the second half of the verse to say, “Even after they are redeemed, they could backslide into their old habits of self-centered behavior… but, through Tzeddakah, that backsliding can be avoided and they can be redeemed.” Giving of ourselves for others changes us, makes us solid and keeps us on the path to redemption.

As we prepare for T’isha B’Av on this Shabbat Hazon, we reflect on the way that disaster comes into the world through habits of putting ourselves first, isolating ourselves from community, from those in need, from the earth and all its inhabitants. The way out of this is to reorient ourselves to the whole, toward giving of ourselves for the good of all. This shift in focus from isolated self to connected relationship is the key to going from the destruction of T’sha B’Av, and the destruction we see coming upon our world today, toward healing and building a thriving, flourishing world.

Shlach L’Chah

July 2, 2021

Drash by Alex Golub

Shabbat shalom. Today we exist at the intersection of two remarkable events.

First, the remarkable story we have just heard: Moses sends twelve spies to scout out the holy land, only to find that all of the spies but Joshua and Caleb believe the local people are too strong and an invasion will fail. The Israelites believe them and complain bitterly that Moses should have left them in Egypt. God decrees that the Israelites will wander for 40 more years in the desert and all the haters will die, so that only Caleb and Joshua will get to enter the promised land.

First, the remarkable story we have just heard: Moses sends twelve spies to scout out the holy land, only to find that all of the spies but Joshua and Caleb believe the local people are too strong and an invasion will fail. The Israelites believe them and complain bitterly that Moses should have left them in Egypt. God decrees that the Israelites will wander for 40 more years in the desert and all the haters will die, so that only Caleb and Joshua will get to enter the promised land.

The second remarkable event taking place this week is, of course, the reopening of our shul with a full service and an in-person minyan. It has been a long process and I want to thank all the other people in this room with me today for making it happen — especially Sandy (who I’ll come back to in a bit). I’d also like to thank everyone watching, and everyone who kept up our observances virtually during this past COVID season, observances which, I’ll be the first to admit, I totally didn’t observe.

The theme that connects these two events is doubt. The Talmud compares the spies’ doubts to a man who worries his wife is a sotah: a woman suspected of adultery. The spies think of God like a partner who you suspect of infidelity. Did they, or didn’t they? Will they, or won’t they? On the one hand, it seems amazing that even now — after the ten plagues, after crossing the Red Sea, after receiving the ten commandments, and after eating manna from heaven — even now after all of the that, the Israelites are unsure of whether or not they can trust God. On the other hand, I imagine that after all that, my baseline sense of reality would be totally destroyed as well. When you live in unusual times, it’s hard to tell what’s normal and what’s not.

God, on the other hand, believes the spies doubt themselves rather than God. The spies say that they are too weak to defeat the Canaanites. “They are giants,” they say. “They looked on us as if we were grasshoppers.” A story in Numbers Rabbah has God replying to the spies, “How do you know what you appeared like to them? Maybe they thought you looked like angels compared to them!” In this drash, the spies’ greatest error is not that they do not trust God, but that they do not trust themselves: they project their own self-doubt onto others, assuming that other people have as low an opinion of them as they do. On this account, the spies’ lack of self-confidence is self-defeating. As Rabbi Sacks observes, “Those who say, “We cannot do it” are probably right.” Or, as Wayne Gretzky puts it: you miss 100% of the shots you don’t take.