Ki Tissa—Drash by Sid Goldstein

Shabbat Shalom

Exodus 4 :10

Moses said to the lord. “I have never been a man of words, either in times past or now. I am slow of speech and slow of tongue.”

And the Lord said to him “Who gives a man speech ?Who makes him dumb., deaf or blind? Is it not I the Lord?”

Moses said “Please, Lord, make someone else your agent.”

The Lord became angry with Moses “There is your brother Aaron the Levite. I know he speaks readily.”

Thus Aaron is introduced into the drama of the Exodus and its aftermath.

Curiosities abound here.

When Hashem sends Moses and Aaron to speak with Pharaoh, he tells Moses “See I place you in the role of a god to Pharaoh with your brother Aaron as your prophet. You shall report all that I command to you. Your brother shall speak to Pharaoh to let the Israelites depart. But I will harden Pharaoh’s heart that I may multiply my signs in the land of Egypt (Exodus 7: 2,3)

So here is the dynamic. Moses complains to Hashem that he is slow of speech. Hashem tells him that he can make him fast of speech but Moses refuses the “honor.” Hashem then puts Aaron in the spokesman’s role and tells Moses that he will harden Pharaoh’s heart.

So- here is a question to ponder: Why didn’t Hashem just make Moses more articulate AND willing to speak to Pharaoh?

If he was capable of hardening Pharaoh’s heart through plague after plague, he was certainly capable of making Moses both articulate and willing.

I believe that all of this was all necessary to get Aaron into the story.

But… Why does the story require Aaron?

Because…without Aaron, we have no Ki Tissa.

Ki Tissa tells the paramount story of the entire Torah.

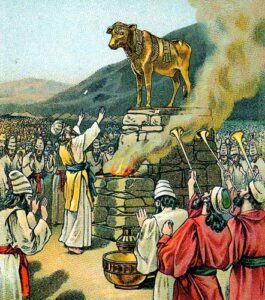

After one of the greatest epics in the history of western religion, Israel’s exodus from Egypt, replete with the parting of the Red Sea–the people demand that Aaron forge an idol.

The sin was so egregious that it caused Hashem to say to Moses “Now do not try to stop Me when I unleash My wrath against them to destroy them.” (Ex. 32:10).

So what do we make of Aaron, the ringleader of the gross act of idolatry?

Remember, Aaron was the de facto leader of the people in the absence of Moses. Thus, it was he whom the Israelites approached with their proposal:

“The people began to realize that Moses was taking a long time to come down from the mountain. They gathered around Aaron and said to him, ‘Make us a god [or an oracle] to lead us. We have no idea what happened to Moses, the man who brought us out of Egypt.’ (Exodus 32:1)

Aaron answered them, “Take off the gold earrings that your wives, your sons and your daughters are wearing, and bring them to me.” So all the people took off their earrings and brought them to Aaron. He took what they handed him, melted it down, cast it into a mold, fashioned it with a graving tool and made it into a calf.

Then the people said, “This, Israel, is your god, who brought you out of Egypt.”

When Aaron saw this, he built an altar in front of the Calf and announced, “Tomorrow there will be a festival to the Lord.” So the next day the people rose early and sacrificed burnt offerings and presented peace offerings. Afterward they sat down to eat and drink and indulge in revelry.” (Ex. 32:2-6)

Aaron is not an insignificant figure. He shared some of the burdens of leadership with Moses. He was about to be appointed High Priest. What then was in his mind while this drama was being enacted?

Let’s look at what the Sages say about Aaron and his role:

Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks documented what the sages say about Aaron:

Essentially there are three lines of defense in the Midrash, the Zohar and the medieval commentators.

According to the first, Aaron was playing for time. His actions were a series of delaying tactics. He told the people to take the gold earrings their wives, sons and daughters were wearing, reasoning to himself: “While they are quarrelling with their children and wives about the gold, there will be a delay and Moses will come” (Zohar).

The second defense is to be found in the Talmud and is based on the fact that when Moses departed to ascend the mountain he left not just Aaron but also Hur in charge of the people (Ex. 24:14). Yet Hur does not figure in the narrative of the Golden Calf. According to the Talmud, Hur had opposed the people, telling them that what they were about to do was wrong, and was then killed by them. Aaron saw this and decided that proceeding with the making of the Calf was the lesser of two evils:

Aaron saw Hur lying slain before him and said to himself: If I do not obey them, they will do to me what they did to Hur. “Shall the Priest [Aaron] and the Prophet [Hur] be slain in the Sanctuary of God?” (Lamentations 2:20). If that happens, they will never be forgiven. Instead, let them worship the Golden Calf, for which they may yet find forgiveness through repentance. (Sanhedrin 7a)

The third, argued by Rabb Abraham Ibn Ezra, the 12 century sage, is that the Calf was not an idol at all. What the Israelites did was, in Aaron’s view, permissible. Remember, their initial complaint was, “We have no idea what happened to Moses.” They did not want a god-substitute. They simply wanted a Moses-substitute, an oracle, something through which they could discern God’s instructions.

What Sacks shows us is nothing less than a systematic attempt in the history of interpretation to both mitigate and minimize Aaron’s culpability.

Yet, with all the generosity anyone can muster, it seems difficult to see Aaron as anything but weak, especially in the reply he gave to Moses when his brother finally appeared and demanded an explanation:

“Do not be angry, my lord,” Aaron answered. “You know how prone these people are to evil. They said to me, ‘Make us a god who will go before us. As for this fellow Moses who brought us up out of Egypt, we don’t know what has happened to him.’ So I told them, ‘Whoever has any gold jewelry, take it off.’ Then they gave me the gold, and I threw it into the fire, and out came this Calf!” (Ex. 32:22-24)

So blaming the people becomes a staple in the history of explaining away sin.

Think about the answer King Saul gave to Samuel, explaining why he did not carry out the Prophet’s instructions.” I saw the people scattering and leaving me. And You had not come at the appointed time.”

Like Aaron, Saul blames the people. He suggests he had no choice. He was passive. Things happened. He minimizes the significance of what has transpired.

In both cases we see weakness, not leadership.

What is really extraordinary, therefore, is the way later tradition made Aaron a hero, most famously in the words of Hillel:

Be like the disciples of Aaron, loving peace, pursuing peace, loving people and drawing them close to the Torah. (Avot 1:12)

There are famous haggadic traditions about Aaron and how he was able to turn enemies into friends and sinners into observers of the law. The Sifra says that Aaron never said to anyone, “You have sinned” – all the more remarkable since one of the tasks of the High Priest was, once a year on Yom Kippur, to atone for the sins of the nation.

So, as with all things Jewish, there is even disagreement about the culpability of Aaron’s involvement in the greatest sin committed in the Torah.

So I will now offer my thoughts, which are neither rabbinical nor of the sages and only carry the weight of minimal scholarship.

Leviticus 10:1

“And Aaron’s sons, Nadab and Abihu, each took his pan, put fire in them, and placed incense upon it, and they brought before the Lord foreign fire, which He had not commanded them. And fire went forth from before the Lord and consumed them, and they died before the Lord.”

When Moses recounted what the Lord told him, Aaron was silent.

Remember, this was supposed to be Aaron’s greatest day – the day when he officially assumed his role as the first High Priest of the Jewish people. He had even slaughtered a calf- of all things- and offered it as a sacrifice for the day.

Yet on that very day, Aaron received his judgement from Hashem. I believe that his two sons died before the Lord because the ‘foreign fire’ they brought was nothing less than a reminder of the fire that Aaron had used to fashion the Golden Calf.

But let me leave you with this thought: Aaron’s sin was necessary.

It was necessary to ensure that the people understood the sanctity of the law they were about to receive.

Remember- it was Hashem who deliberately placed Aaron in the position to speak the words that Moses could not.

With a highly Jewish sense of irony, the spokesman who looked eye-to-eye with and spoke directly to Pharaoh, could not convince his own people to simply be patient wait for Moses to return.

Ki Tissa, then, is at least partially the story of Aaron, the necessary man.

Like most of the necessary men in the Torah, Aaron takes actions for good and for evil.

And like all necessary men from Abraham on down, he both reaped the glory and paid the price.

Shabbat Shalom.