From My Jewish Learning

Reprinted with permission from My Jewish Learning

Jewish Humor

What Makes It So Popular?

March 2, 2022

The Torah tells us that Sarah, the matriarch of the Jewish people, laughed when told she’d give birth in her old age. Since that moment, it seems, Jews have continued laughing — at themselves and their predicaments, at each other, sometimes, even at God. And beneath that laughter, and the humor that sparked it, lies Jewish humor as a genre.

The Torah tells us that Sarah, the matriarch of the Jewish people, laughed when told she’d give birth in her old age. Since that moment, it seems, Jews have continued laughing — at themselves and their predicaments, at each other, sometimes, even at God. And beneath that laughter, and the humor that sparked it, lies Jewish humor as a genre.

The genre got its start in 18th-century Eastern Europe, where Yiddish folk tales found the humor in the often-difficult everyday life of the shtetl (village). The great Jewish novelists and playwrights–like Sholem Aleichem, whose stories were the basis for the musical hit Fiddler on the Roof — infused their writing with this humor, enshrining it for posterity and ensuring that humor would become one of the hallmarks of Yiddish literature.

With the steady growth of the American Jewish community and the Jews’ acceptance into mainstream American society in the 20th century, Jewish humor likewise found a welcoming home. Beginning with Yiddish publications and plays and gradually moving to English, Jewish comedians poked fun at the immigrant experience and the foibles and frustrations of Jewish-American life.

But a funny thing happened on the Jews’ way to acculturation in their new home: As the immigrant experience faded and the old jokes began losing their audience, Jewish humor expanded beyond the borders of the Jewish-American neighborhoods and Catskills hotels (known as the Borscht Belt) and was embraced by America at large.

Jewish humor in the second half of the 20th century became virtually synonymous with American humor in general. From Sid Caesar, Mel Brooks and Lenny Bruce to Jerry Seinfeld, Sarah Silverman and Jon Stewart, the great American comedians, comic actors, and humor writers were by and large Jewish. Naturally they often infused their humor with a decidedly Jewish sensibility.

Jewish humor in the second half of the 20th century became virtually synonymous with American humor in general. From Sid Caesar, Mel Brooks and Lenny Bruce to Jerry Seinfeld, Sarah Silverman and Jon Stewart, the great American comedians, comic actors, and humor writers were by and large Jewish. Naturally they often infused their humor with a decidedly Jewish sensibility.

So what makes humor Jewish? Defining it is no easy task, but there are some characteristics that stand out as common to much of Jewish humor. Jewish humor, for instance, laughs at authority and blurs boundaries, such as those between sacred and secular or Jew and non-Jew. It also displays a fascination with language and (often twisted) reasoning. And, not surprisingly, Jewish humor often played the role of coping mechanism. With the anti-Semitism, poverty, and political uncertainties Jews faced throughout so much of their history, there often seemed little to do but laugh at the absurdity of the situation.

So what makes humor Jewish? Defining it is no easy task, but there are some characteristics that stand out as common to much of Jewish humor. Jewish humor, for instance, laughs at authority and blurs boundaries, such as those between sacred and secular or Jew and non-Jew. It also displays a fascination with language and (often twisted) reasoning. And, not surprisingly, Jewish humor often played the role of coping mechanism. With the anti-Semitism, poverty, and political uncertainties Jews faced throughout so much of their history, there often seemed little to do but laugh at the absurdity of the situation.

So they did. And we are still reaping the benefits of the humor they produced. While there’s a lot to learn about Jewish humor, there’s even more to laugh about. Humor is one of those things you need to experience to truly understand. Of course, what’s funny to one person is not funny to the next person — though the world of Jewish humor, like Jewish argument-is broad enough to encompass virtually any taste or any opinion. So, smile and enjoy!

Sermons in the Synagogue

November 1, 2021

Like spiritual leaders in many religions, Jewish clergy normally deliver sermons during worship services. often during a synagogue’s main Shabbat service, usually on Saturday mornings. Sermon topics can vary widely, but often touch in some way in the weekly Torah portion. Rabbinic preaching is considered by some worshippers to be the centerpiece of the service. Anthologies of rabbinic sermons were routinely gathered into published volumes in the United States in the mid-20th century, while more recently they are often found on synagogue websites. The ability to deliver an inspiring sermon is considered to be a core function of the pulpit Rabbi, and many seminaries require students to take courses in preaching.

Like spiritual leaders in many religions, Jewish clergy normally deliver sermons during worship services. often during a synagogue’s main Shabbat service, usually on Saturday mornings. Sermon topics can vary widely, but often touch in some way in the weekly Torah portion. Rabbinic preaching is considered by some worshippers to be the centerpiece of the service. Anthologies of rabbinic sermons were routinely gathered into published volumes in the United States in the mid-20th century, while more recently they are often found on synagogue websites. The ability to deliver an inspiring sermon is considered to be a core function of the pulpit Rabbi, and many seminaries require students to take courses in preaching.

Rabbinic sermonizing has a long history in Judaism. The Talmud is replete with references to rabbinic lectures and hints that the tradition of the Sabbath sermon was known in ancient times. One passage in Brachot records the practice of rabbis running on the Sabbath to hear a lecture. Running is frowned upon on the Sabbath, but the Talmud seems to approve of the practice when its objective is hearing words of the Torah. The biblical commentator Rashi writes that the role of prophet is to rebuke the people. The Talmud established a distinction among rabbinic orators that would hold true for centuries—between speakers who focused largely on the law and those who were more akin to storytellers. The Talmud in Sotah tells a story of two rabbis: Rabbi Abbahu, who taught matters of aggadah (the non-legalistic Talmudic texts that include folklore and parables), and Rabbi Hiyya bar Abba, who taught matters of Jewish law. Rabbi Abbahu was the more popular of the two, which offended Rabbi Hiyya and prompted Rabbi Abbahu to seek to appease him.

These two types of preachers would come to be known as a darshan and a maggid. Darshan, from the Hebrew word for “demand” or “search,” referred to a scholarly teacher who focused on textual exegesis. The word is used in many biblical and rabbinic texts to refer to individuals who publicly taught Torah. The word Midrash itself is derived from the same root as darshan. In modern times, a synagogue sermon is sometimes called a “drash.” The other type, the maggid, takes its name from the Hebrew word for “to tell” or “to relate.” The maggid tradition reached its peak in Europe, where rabbis largely left sermonizing to these skilled raconteurs who were not necessarily rabbis themselves.

Maggidim were often itinerant preachers who traveled from to town to town telling stories that contained pearls of religious wisdom, though larger communities sometimes had a resident maggid. Among the best known is Dov Ber of Mezeritch, also known as the Maggid of Mezeritch, an 18th-century preacher who was a disciple of Rabbi Yisrael Baal Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidism. Today, preaching is a taught discipline in rabbinical seminaries, where it is known as homiletics. Training typically involves some combination of theory and practice, analyzing sermons considered to be models of the form alongside student attempts to craft and deliver sermons of their own. Both Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, the Reform movement seminary, and the Jewish Theological Seminary, the flagship Conservative seminary, have well-established traditions requiring students to deliver a so-called “senior sermon” prior to graduation.

Why Study Torah?

For a couple of millennia, studying Torah was just a given for male Jews. Of course you’d learn it — or at least read it in bite-sized chunks every Shabbat in synagogue, in a never-ending cycle where not only was the yearly reading finished and then immediately begun again on the Simchat Torah festival, but each week’s chunk was trailed on Shabbat afternoon with a little preview of the following week’s portion. But this is the 21st century, and just because something has been done for millennia by millions of our forebears isn’t reason enough for us to continue. So what might be the reasons now? We’ll need to do a bit of defining first. After all, there are two key words in this question which are not as obvious as they might look – Torah and study. The word Torah means a multiplicity of things, which in itself might be a cause to study it at least a bit. After all, even if you choose to reject Torah as an important part of your Jewishness, it makes sense to know what it is you are rejecting, if only in outline.

For a couple of millennia, studying Torah was just a given for male Jews. Of course you’d learn it — or at least read it in bite-sized chunks every Shabbat in synagogue, in a never-ending cycle where not only was the yearly reading finished and then immediately begun again on the Simchat Torah festival, but each week’s chunk was trailed on Shabbat afternoon with a little preview of the following week’s portion. But this is the 21st century, and just because something has been done for millennia by millions of our forebears isn’t reason enough for us to continue. So what might be the reasons now? We’ll need to do a bit of defining first. After all, there are two key words in this question which are not as obvious as they might look – Torah and study. The word Torah means a multiplicity of things, which in itself might be a cause to study it at least a bit. After all, even if you choose to reject Torah as an important part of your Jewishness, it makes sense to know what it is you are rejecting, if only in outline.

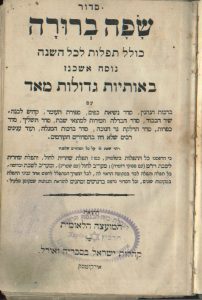

At its simplest, Torah is the text of the first five books of the (Jewish) Bible. But Torah for Jews always meant something more than that. Together with the plain text comes a wealth of tradition, extensions and challenges which are known as the Oral Torah and can be found in the great rabbinic texts – the Talmud, the Midrash and the still unfolding library of commentary and quest from a vast variety of viewpoints. Now, study. Many sincere Christians who read the Bible regularly simply sit and contemplate the text. Frequently, such Bible study involves clarification and the addition of information from the historical record that outline the customs of the time or set the narrative in context. In terms of the Jewish Bible, they will pick out those bits that seem most telling for them – a rich story or an important teaching.

But that’s not the Jewish way. Go into any synagogue and look at the Bibles that are used to follow the Torah reading during the service. Pretty well invariably, it will have the Hebrew text, translated into the vernacular as literally as possible, accompanied by a whole host of commentary. Every text of Torah is an invitation to wonder and argument. Torah is never simply obvious. The Jewish approach has always been, “If that’s what it says, then WHAT does it mean?” Each reading demands an explanation. This is what is meant by study. By all means, use your own intellectual resources. After all, the Torah belongs to every Jew. But let us also be honest about our own limitations. The thoughtful Jew, the humble scholar, can stand on the shoulders of giants and use their thinking too. So study in this sense involves exploration, challenge, questioning, entering into a conversation with our own past and our global present. In the end, that’s the how of Torah study. Now to the why.

It is not as a result of genetics that Jews have regularly shown themselves to be successful scholars. It’s nurture, not nature. A close study of Genesis will tell you everything you need to know about family dynamics and how to get them wrong. It stretches and challenges our understanding of human responsibility and the order of the world. It goes over and over how spouses might behave toward each other and how siblings, parents and children can mess up – and sometimes come right too. The remaining four books of the Torah are a close study in how to organize a society. The demand for Jews to care for the stranger – the most repeated injunction in the whole Torah — has not yet been fully grasped in all its implications by us, let alone the rest of humanity. The laws of inheritance, damages, social responsibility, warfare, property, inclusion, environmental care – you name it, it can be found in the Torah and the commentaries that arise therefrom.

The Torah asks us to consider miracles — what they are, if they exist, and how they work. It warns us not to trust miracle-makers, and yet 21st century folk are still easily misled. The good are sometimes Jewish and sometimes not. And certainly it offers a world where Jews are often backsliding and of poor quality. Yet, despite all of this it continues to play an optimistic and upbeat tune. This essay can only scratch the surface of what there is in Torah which might compel us to study it. But in the end, it boils down to this: Why would you choose to be an ignorant Jew? Surely you owe yourself – and the friends you can study it with – a better fate than that.

Jews and the Film Industry

August 2, 2021

Did you know that the Hollywood dream factories were formed by a small group of top-level Jewish-born movie moguls, or entrepreneurs? The group included industry leaders such as: Marcus Loew, Adolph Zukor, Sam Goldwyn, Carl Laemmle, the Selznicks, Jesse Lasky, William Fox, the Warner Brothers, Louis B. Mayer, B.P. Schulberg and Harry Cohn. Most of the moguls could be classified as second-generation American Jews, from poor or modest-income families. Many moguls came to the motion picture industry from retail trades, particularly the garment industry. Zukor and Loew began as furriers, Fox and Laemmle as clothing merchants, and Goldwyn as a glove salesman. Control was enterprisingly gained over theaters and, later, over studios, linking distribution and production. In both the clothing and motion picture industries, Jewish entrepreneurs, starting from a mass distribution base, created mass production industries for garments and entertainment.

Did you know that the Hollywood dream factories were formed by a small group of top-level Jewish-born movie moguls, or entrepreneurs? The group included industry leaders such as: Marcus Loew, Adolph Zukor, Sam Goldwyn, Carl Laemmle, the Selznicks, Jesse Lasky, William Fox, the Warner Brothers, Louis B. Mayer, B.P. Schulberg and Harry Cohn. Most of the moguls could be classified as second-generation American Jews, from poor or modest-income families. Many moguls came to the motion picture industry from retail trades, particularly the garment industry. Zukor and Loew began as furriers, Fox and Laemmle as clothing merchants, and Goldwyn as a glove salesman. Control was enterprisingly gained over theaters and, later, over studios, linking distribution and production. In both the clothing and motion picture industries, Jewish entrepreneurs, starting from a mass distribution base, created mass production industries for garments and entertainment.

By the 1930s, six of the eight major studios were Jewishly controlled and managed. In addition, persons of Jewish birth were prominent among the second and third level of business-oriented producers, managers, assistants, agents and lawyers. During this period, however, almost no films were made about specifically Jewish settings, experiences, or characters. This was because the moguls attempted to appeal to a wide audience and to create universal stories. Though most of the moguls came from observant Jewish homes and learned some Hebrew and/or had been bar mitzvahed, their Jewishness usually showed up in the use of some Yiddish words, temple membership but infrequent attendance, and support for Jewish philanthropy. Jewish Hollywood was somewhat socially separate in structure, making up its own social circles of Jewish friends and associates for job support, social support, and even marriage (Louis B. Mayer’s daughter married David Selznick). As immigrants becoming Americans, the moguls had a special sense of, or “instinct” for, what the movie-goer wanted and liked. This immigrant enthusiasm for American popular culture, and this understanding of mass American tastes, took different shapes and forms at the different Jewish-led studios. While MGM, for instance, under Mayer, turned out pictures that have been described as folksy, romantic, sentimental, glossy films for the middle class, the Warner Brothers, under Jack Lo Warner, produced crime stories, melodramas, biographies, and socially aware films for and about the working class. Both sets of films were variations on themes of American popular culture, as seen through historical immigrants’ lenses.

A History of Jewish Art

July 2, 2021

Reprinted with permission from My Jewish Learning

Jewish visual arts date back to the biblical Bezalel, commissioned by God to create the Tabernacle in the wilderness. Since then, Jewish visual arts have flourished, bearing the imprint of Jewish wanderings around the globe. Jewish art divides into categories of art: folk-art, such as paper cuts; ritual art–artistic renditions of ritual objects; and art by Jews, which encompasses a broad range of visual expression by Jewish artists, from painting to sculpture to avant-garde art.

Jewish visual arts date back to the biblical Bezalel, commissioned by God to create the Tabernacle in the wilderness. Since then, Jewish visual arts have flourished, bearing the imprint of Jewish wanderings around the globe. Jewish art divides into categories of art: folk-art, such as paper cuts; ritual art–artistic renditions of ritual objects; and art by Jews, which encompasses a broad range of visual expression by Jewish artists, from painting to sculpture to avant-garde art.

What Is Jewish Art?

Words and ideas have always been a focal point in Jewish life, but fine arts and handicrafts have played a prominent role as well. The Jewish attitude toward art has been influenced by two contradictory factors: The value of hiddur mitzvah (beautification of the commandments) encourages the creation of beautiful ritual items and sacred spaces, while some interpret the Second Commandment (forbidding “graven images”) as a prohibition against artistic creations, lest they be used for idolatry.

With the age of Enlightenment in Europe, Jewish artists left the ghetto to become prominent artists worldwide. In their visual arts, Jewish artists displayed varied relationships with their Jewish identities, and some Jewish artists did not incorporate their Jewishness into their artistic work at all. With the rise of such artists came the question of what constitutes “Jewish art,” a question still debated today. Some artists, such as Marc Chagall, clearly drew upon their Jewish heritage for their work. For others, such as Camille Pissaro, Judaism was tangential or even irrelevant to their work.

Regardless of how one might define “Jewish art,” Jewish artists — painters, sculptors, and others — have flourished in North America, Europe and Israel.

Jewish folk art has pervaded homes and synagogues for centuries. This has included the mizrach, an emblem placed on the eastern wall of the home to remind family members which way to direct their prayers; the shivitti, an adornment in the synagogue intended to focus attention; and the art of micrography, which uses sacred words and texts to create drawings. Artistic ritual art has included kiddush cups, mezuzot, candlesticks, and more. These art forms were once an expression of folk-piety by Jews who worked without the benefit of artistic training. Today Jewish folk art has grown in sophistication as trained artists focus their skills and sensibilities on these traditional crafts.

Israeli Art

From the beginning of the 20th century, visual arts in Israel were emblematic of the unique encounter between East and West in Israel. Artistic visual expression was enhanced in Israel in 1906 with the founding of the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Crafts in Jerusalem. The school aimed to create an “original Jewish art” by blending European artistic techniques with Middle Eastern influences. Artists from this school — along with other artists who were part of the burgeoning visual arts movement — created paintings of biblical scenes depicting romanticized perceptions of the past linked to utopian visions of the future. Examples of such artists include Shmuel Hirszenberg, Anna Ticho, Nachum Gutman, Mordecai Arden and Reuven Rubin.

As the State of Israel has matured, so too have its visual arts. Yaakov Agam has attracted international attention for his unique use of shape and dimension. As Israel has continued to attract Jewish immigrants from around the globe, they have brought with them their artistic training and sensitivities shaped by their host culture. Throughout Israeli history, the visual arts have been used to interpret and make meaning of the difficulties of Israeli and Jewish art.

The History of Jews in Ireland

Reprinted with permission from My Jewish Learning

Jews have made their home in Ireland for centuries, and many have risen to be successful and prominent figures in politics, business, and theology. Ireland produced Chaim Herzog, the sixth president of Israel, and Leopold Bloom, the hero of James Joyce’s “Ulysses,” a canonical Irish text, is a Jew. However, the Irish Jewish community can hardly be called thriving, and Jews have not always been welcomed in this predominantly Catholic country. During the Holocaust, Ireland denied refuge to Jews in search of escape from the Nazis, and anti-Semitism has been a minor but persistent problem.

Jews first came to Ireland in 1079, when a group of five merchants, probably from Normandy, petitioned for admission and were rejected, according to the “Annals of Inisfallen,” a chronicle of the medieval history of Ireland. There were some Jews in Ireland during the 12th and 13th centuries, but when Britain expelled all of its Jews in 1290, the Jews of Ireland, too, were forced to leave. A Jewish community wasn’t reinstated until late in the 15th century, as refugees from the Inquisition in Spain and Portugal sought a safe haven. There were only a handful of Jews living in Ireland for the next 300 years, most of whom immigrated due to persecution in other parts of Europe. For the most part Jews lived (and still live) in and around Dublin. There was a congregation in Cork from 1725 to 1796, and another that was established around 1860. These communities were mostly populated by people in the import business, specifically wine imports.

In 1822 a small group of Jews arrived from Germany, Poland, and England and began to actively build the Jewish community. The Jewish population grew from 453 in 1881 to almost 4,000 in 1901. Small communities emerged in Limerick, Waterford, Belfast and Londonderry. Although the Irish Jewish community never officially took sides regarding the Irish-British conflict, the community was generally known to be sympathetic to the Irish nationalist cause. The Easter rebellion of 1916 saw many Jewish homes sheltering rebels, and Robert Briscoe, Dublin’s first Jewish mayor (but not Ireland’s first Jewish mayor — that honor goes to William Annyas, elected in 1555), was himself a member of the Irish Republican Army. Former Chief Rabbi of Ireland, Dr. Isaac Herzog, was a friend of Taoiseach (Irish for prime minister) Eamon de Valera. Additionally, a Jewish lawyer, Michael Noyk, defended members of the Irish Republican Sinn Fein Party and was friends with Michael Collins, the Irish Republican nationalist. The Irish constitution of 1937 recognized Judaism as a minority faith, and Jews were assured freedom from discrimination.

The Jews of Ireland were involved in anti-Nazi activism as early as 1933, when Chief Rabbi Herzog organized protests against the Third Reich. Robert Briscoe, who at that time was a prominent and well-respected lawmaker with the Fianna Fáil party, continuously spoke out against anti-Semitism. But Herzog and Briscoe’s efforts were to no avail in 1938 at the international conference at Evian-Les-Bains. It was in Evian that world leaders came together to discuss the European refugee problem, and Ireland effectively closed its doors to all refugees. World War II was a troublesome time for Jews around the world, but the Irish Jewish community was relatively safe. Ireland was considered a neutral country, but some anti-British sympathy led to limited support of Germany, mostly in the spirit of “the enemy of my enemy is my friend.” Nazi records from the Wannsee Conference in 1942 mark 4,623 Irish Jews for death, under the assumption that Ireland would eventually fall under the control of the Third Reich. The Nazis were nowhere near successful in this venture. There is only one known Irish Jewish casualty of the Holocaust.

Once the war was over, Taoiseach Eamon de Valera allowed 175 Jewish orphans from Czechoslovakia to stay in Clonyn Castle in Delvin, Co. Westmeath for about 15 months before they emigrated to the United States and to Israel. The Irish Republican Army ran guns to the Hagenah in Palestine during the 1948 War of Independence. The Jewish Population in Ireland peaked in 1955 at about 5,400 people. When economic conditions sagged in the 1970s, many Irish Jews emigrated to Israel. Today, approximately 2,400 Jews live in Ireland, mostly in Dublin. The City sustains one Orthodox and one Reformed Congregation. There is also one small mixed Conservative and Reformed Congregation in Cork.

Jewish Custom and Jewish Law

Reprinted from My Jewish Learning

Jewish custom — known in Hebrew as a minhag — is a religious practice that, though sometimes very widely practiced, does not carry the force of Jewish law and is thus not considered mandatory by traditional Jews. Customs cover an extremely wide range of Jewish rituals, from variations in the order or language of particular prayers, to swinging a chicken over one’s head prior to Yom Kippur, to the nearly universal practice of smashing a glass at the conclusion of a wedding ceremony. Customs typically have folk origins, but there are instances in which they may have been imposed by religious authorities. Other customs were maintained for so long and adopted so widely that they have become enshrined as obligations in Jewish legal codes and are no longer, strictly speaking, customs at all. Still others may have been adapted from practices of the cultures in which Jews lived and were only later sanctioned by Jewish authorities.

Jewish custom — known in Hebrew as a minhag — is a religious practice that, though sometimes very widely practiced, does not carry the force of Jewish law and is thus not considered mandatory by traditional Jews. Customs cover an extremely wide range of Jewish rituals, from variations in the order or language of particular prayers, to swinging a chicken over one’s head prior to Yom Kippur, to the nearly universal practice of smashing a glass at the conclusion of a wedding ceremony. Customs typically have folk origins, but there are instances in which they may have been imposed by religious authorities. Other customs were maintained for so long and adopted so widely that they have become enshrined as obligations in Jewish legal codes and are no longer, strictly speaking, customs at all. Still others may have been adapted from practices of the cultures in which Jews lived and were only later sanctioned by Jewish authorities.

Halacha (Jewish Law) vs. Minhag (Custom)

Jewish law is called halacha (literally the path or the way) and is grounded in the Torah itself or later rabbinic rulings. In the former category are obligations that are explicit in the Bible, such as prohibitions on murder, idol worship and certain sexual behavior.

Rabbinic laws are of two types:

- A gezerah (literally “fence”) is a rabbinic rule imposed to serve as a guard against violating a more serious prohibition, such as the ban on touching objects used to perform forbidden actions on the Sabbath;

- A takkanah (literally remedy or fixing) is a piece of rabbinic legislation enacted for some other purpose, such as the celebration of the holiday of Hanukkah.

Customs are established practices that are not legally obligatory and do not derive from biblical or rabbinic mandates.They cover a very broad range of religious practices, including (but not limited to):

- The manner, order and liturgy of prayer;

- Certain wedding rituals;

- Styles of Torah chanting and of decorative Torah scroll coverings;

- Various holiday practices.

Many customs differ based on Jews’ ethnicities — Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews observe many different customs from one another. Among them is the custom that Ashkenazi men begin wearing a prayer shawl only once they are married, while Sephardic custom is generally from a boy’s bar mitzvah. There are many modern congregations where Jewish women also wear prayer shawls.) However, there are also a vast number of variations in customs even among Ashkenazi and Sephardic subgroups. The post-Passover celebration of Mimouna, for example, is a custom that originated among the Sephardic Jews of North Africa. The wearing of long curled payot is a custom practiced generally only by Hasidic Ashkenazi Jews.

Many customs differ based on Jews’ ethnicities — Ashkenazi and Sephardic Jews observe many different customs from one another. Among them is the custom that Ashkenazi men begin wearing a prayer shawl only once they are married, while Sephardic custom is generally from a boy’s bar mitzvah. There are many modern congregations where Jewish women also wear prayer shawls.) However, there are also a vast number of variations in customs even among Ashkenazi and Sephardic subgroups. The post-Passover celebration of Mimouna, for example, is a custom that originated among the Sephardic Jews of North Africa. The wearing of long curled payot is a custom practiced generally only by Hasidic Ashkenazi Jews.

Some practices that began as customs became so well established in Jewish life that they are now broadly considered obligatory. One example is the wearing of a kippah by men. (There are many modern congregations where Jewish women also wear Kippot). The practice was described in the Talmud as the pious habit of a particular rabbi and codified by later rabbinic authorities as required at particular times — for Maimonides, during prayer; for the Shulchan Aruch, when walking more than four cubits. (The Shulchan Aruch elsewhere records the view of some authorities that it is forbidden to recite God’s name when not wearing a head covering). In the 20th century, the American Orthodox authority Rabbi Moshe Feinstein issued a special dispensation for men to not wear a kippah at work if necessary — implying that the practice is generally obligatory. Another example is the Ashkenazi ban on eating rice, lentils and legumes — known as kitniyot — during Passover. Though the practice of avoiding rice on Passover is noted in the Talmud, it only came into force as a broad ban centuries later. The ban remains in force among most Ashkenazi Jews today, though the Conservative movement, in a 2015 decision, overturned it.

Over the centuries, rabbinic authorities have employed various formulations to describe the obligatory nature of longstanding customs. When discussing the practice of observing a second day of festivals outside of Israel — originally instituted to ensure the proper day of the holiday was observed in places where word of the new month took a long time to arrive — the Talmud asks why the practice persists even after the establishment of a fixed calendar made it unnecessary. The Talmud replies: “Take care to observe the customs of your fathers that you received.”

Some customs are practiced by only small minorities of Jews. German Jews, for example, ritually wash their hands before reciting the Kiddush prayer over wine at the Sabbath meal, while most other Jews wash their hands after drinking the wine. Some Jews stand for the Kiddush, others sit, and some stand for the first half and sit for the second half. Among the Jews of Gibraltar, sand is added to the charoset dish on Passover to enhance its symbolism of the bricks used in building by the Hebrew slaves in ancient Egypt. Another Passover custom, practiced by Persian Jews, is to whip seder participants with scallions in remembrance of the pain of bondage.

Some customs are practiced by only small minorities of Jews. German Jews, for example, ritually wash their hands before reciting the Kiddush prayer over wine at the Sabbath meal, while most other Jews wash their hands after drinking the wine. Some Jews stand for the Kiddush, others sit, and some stand for the first half and sit for the second half. Among the Jews of Gibraltar, sand is added to the charoset dish on Passover to enhance its symbolism of the bricks used in building by the Hebrew slaves in ancient Egypt. Another Passover custom, practiced by Persian Jews, is to whip seder participants with scallions in remembrance of the pain of bondage.

Where Did the Dreidel Game Come from?

January 10, 2021

Reprinted with permission from My Jewish Learning

The dreidel or sevivon is perhaps the most famous custom associated with Hanukkah. Indeed, various rabbis have tried to find an integral connection between the dreidel and the story of Hanukkah. The standard explanation is that the letters nun, gimmel, hey, shin, which appear on the dreidel in the Diaspora, stand for nes gadol haya sham, “a great miracle happened there,” while in Israel the dreidel says nun, gimmel, hey, pey, which means “a great miracle happened here.” One 19th-century rabbi maintained that Jews played with the dreidel in order to fool the Greeks if they were caught studying Torah, which had been outlawed. Others figured out an elaborate set of numerological explanations based on the fact that every Hebrew letter has a numerical equivalent and word plays for the letters nun, gimmel, hey, shin. For example, nun, gimmel, hey, shin in gematria equals 358, which is also the numerical equivalent of mashiach or Messiah! Finally, the letters nun, gimmel, hey, shin are supposed to represent the four kingdoms that tried to destroy us in ancient times: N = Nebuchadnetzar = Babylon; H = Haman = Persia = Madai; G = Gog = Greece; and S = Seir = Rome.

The dreidel or sevivon is perhaps the most famous custom associated with Hanukkah. Indeed, various rabbis have tried to find an integral connection between the dreidel and the story of Hanukkah. The standard explanation is that the letters nun, gimmel, hey, shin, which appear on the dreidel in the Diaspora, stand for nes gadol haya sham, “a great miracle happened there,” while in Israel the dreidel says nun, gimmel, hey, pey, which means “a great miracle happened here.” One 19th-century rabbi maintained that Jews played with the dreidel in order to fool the Greeks if they were caught studying Torah, which had been outlawed. Others figured out an elaborate set of numerological explanations based on the fact that every Hebrew letter has a numerical equivalent and word plays for the letters nun, gimmel, hey, shin. For example, nun, gimmel, hey, shin in gematria equals 358, which is also the numerical equivalent of mashiach or Messiah! Finally, the letters nun, gimmel, hey, shin are supposed to represent the four kingdoms that tried to destroy us in ancient times: N = Nebuchadnetzar = Babylon; H = Haman = Persia = Madai; G = Gog = Greece; and S = Seir = Rome.

As a matter of fact, all of these elaborate explanations were invented after the fact. The dreidel game originally had nothing to do with Hanukkah; it has been played by various people in various languages for many centuries. In England and Ireland there is a game called totum or teetotum that is especially popular at Christmastime. In English, this game is first mentioned as “totum” ca. 1500-1520. The name comes from the Latin “totum,” which means “all.” By 1720, the game was called T- totum or teetotum, and by 1801 the four letters already represented four words in English: T (Take all); H (Half); P (Put down); and N (Nothing). Our Eastern European game of dreidel (including the letters nun, gimmel, hey, shin) is directly based on the German equivalent of the totum game: N (Nichts = nothing); G (Ganz = all); H (Halb = half); and S (Stell ein = put in). In German, the spinning top was called a “torrel” or “trundl,” and in Yiddish it was called a “dreidel,” a “fargl,” a “varfl” (something thrown), “shtel ein” (put in), and “gor, gorin” (all).

As a matter of fact, all of these elaborate explanations were invented after the fact. The dreidel game originally had nothing to do with Hanukkah; it has been played by various people in various languages for many centuries. In England and Ireland there is a game called totum or teetotum that is especially popular at Christmastime. In English, this game is first mentioned as “totum” ca. 1500-1520. The name comes from the Latin “totum,” which means “all.” By 1720, the game was called T- totum or teetotum, and by 1801 the four letters already represented four words in English: T (Take all); H (Half); P (Put down); and N (Nothing). Our Eastern European game of dreidel (including the letters nun, gimmel, hey, shin) is directly based on the German equivalent of the totum game: N (Nichts = nothing); G (Ganz = all); H (Halb = half); and S (Stell ein = put in). In German, the spinning top was called a “torrel” or “trundl,” and in Yiddish it was called a “dreidel,” a “fargl,” a “varfl” (something thrown), “shtel ein” (put in), and “gor, gorin” (all).

When Hebrew was revived as a spoken language, the dreidel was called, among other names, a sevivon, which is the one that caught on. Thus the dreidel game represents an irony of Jewish history. In order to celebrate the holiday of Hanukkah, which celebrates our victory over cultural assimilation, we play the dreidel game, which is an excellent example of cultural assimilation! Of course, there is a world of difference between imitating non-Jewish games and worshiping idols, but the irony persists down through the ages.

The Shema: How Listening Leads to Oneness

November 29, 2020

From My Jewish Learning, reprinted with permission.

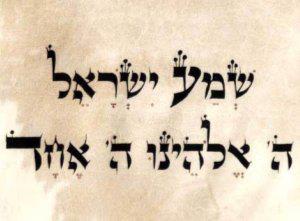

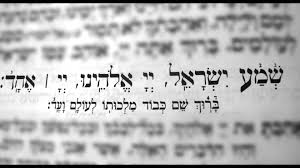

שמע ישראל ה’ אלהנו ה’ אחד

Shema Yisrael, Adonai Eloheinu, Adonai Echad

Hear O Israel, the Lord our God, the Lord is one.

These words, commonly known as the Shema, are traditionally recited by Jews as we begin and conclude each day. Bookending not just our days but our lives, the Shema is also commonly the first prayer we are taught as children and is the final prayer we utter on our deathbed as we pass from this world. The Shema is the mantra of Judaism, its message foundational to what it means to live as a Jew of faith in this world. The Shema begins with an imperative: Listen! Just that word alone is a powerful call. Listening is not an easy thing to do. More than the simple act of hearing, true listening requires us to open ourselves up to another’s experience so that heart touches heart and we are changed. It is — in philosopher Martin Buber’s framework — what allows us to develop an I-thou, rather than an I-it, relationship. Buber describes listening as “something we do with our full selves by sensing and feeling what another is trying to convey so that together we can remove the barrier between us.”

In Judaism, the act of listening is the key to unlocking bounty and blessing. In Deuteronomy, as the Israelites wind down their wandering in the wilderness and prepare to enter the land of Israel, Moses instructs them emphatically using this same word — shema. “If you listen, truly listen,” Moses says, all will be good. If not, curses will follow. On this verse, the Hasidic commentator the Sefat Emet references a line from the Midrash : “Happy is the one whose “Listenings are to Me.” Adding his own commentary, he writes: “‘Listenings’ means that one should always be prepared to receive and listen closely to the words of God. The voice of God’s word is in everything since all were created by God’s utterance.” Each of us, no matter how seemingly different we are from one another, is created by God. The Shema calls on us not merely to listen, but to remember that despite our differences, there is one force of connection and transformation in the universe that animates and unites us all. “The Lord, our God, the Lord is One,” the Shema continues.

In Judaism, the act of listening is the key to unlocking bounty and blessing. In Deuteronomy, as the Israelites wind down their wandering in the wilderness and prepare to enter the land of Israel, Moses instructs them emphatically using this same word — shema. “If you listen, truly listen,” Moses says, all will be good. If not, curses will follow. On this verse, the Hasidic commentator the Sefat Emet references a line from the Midrash : “Happy is the one whose “Listenings are to Me.” Adding his own commentary, he writes: “‘Listenings’ means that one should always be prepared to receive and listen closely to the words of God. The voice of God’s word is in everything since all were created by God’s utterance.” Each of us, no matter how seemingly different we are from one another, is created by God. The Shema calls on us not merely to listen, but to remember that despite our differences, there is one force of connection and transformation in the universe that animates and unites us all. “The Lord, our God, the Lord is One,” the Shema continues.

The force that we call Adonai, others call by other names. Each of us has our own particular path, but ultimately they lead to the same place. Beginning with listening and ending with oneness, the Shema invites us to deepen our capacity to listen — to ourselves, to the Divine, and to those around us, to develop an I-thou relationship with the rest of humanity. Its daily recitation reminds us to build bridges rather than barriers so that we may touch upon — even if only for brief moments at a time — that place in which we all are one.

The force that we call Adonai, others call by other names. Each of us has our own particular path, but ultimately they lead to the same place. Beginning with listening and ending with oneness, the Shema invites us to deepen our capacity to listen — to ourselves, to the Divine, and to those around us, to develop an I-thou relationship with the rest of humanity. Its daily recitation reminds us to build bridges rather than barriers so that we may touch upon — even if only for brief moments at a time — that place in which we all are one.

Atah Chonen: A Prayer for Wisdom

October 2, 2020

Reprinted with permission from My Jewish Learning

Prayer offers us a daily opportunity to embrace God with words while seeking — through the language of petition and supplication — a way to articulate our most profound needs. It is in the searching and wrestling that we gain clarity. This kind of penetrating lucidity comes in that rare moment – and almost always when we do not set out to achieve it – that we are gifted with an intellectual or emotional breakthrough. The Amidah is the spinal cord of the Jewish prayer experience; all prayer that precedes it is preparation to ask God to meet our needs with a combination of humility and spiritual audacity. In the very first of our requests, we ask for the wisdom to be God-like in the day ahead. In the blessing Atah Chonen we recite: “You grace humans with wisdom and teach humanity perception. Bestow upon us Your knowledge, insight and understanding. Blessed are you the grantor of wisdom.” In this prayer, we ask that God offer us a sliver of divine insight. We firm up our minds to problem-solve and manage life’s complexities. Intelligence involves the exquisite and often contradictory balance of curiosity, instinct, patience, caution and risk. What may be sensible in one situation is foolish in another. Thus, we pray for knowledge and introduce every other blessing that follows in the Amidah with this request. On Saturday night we acknowledge the onset of the new week with a special prayer tucked into Ata Chonen, because we need this insight for the whole week ahead.

The practice of havdalah, or separation (also the name for the ritual at the close of Shabbat), requires the perception to categorize and compartmentalize, to know the difference between the holy and the profane. The idea of apportioning wisdom appears in the Hebrew Bible on numerous occasions. In the building of the Tabernacle, God tells Moses to appoint Bezalel: “I have endowed him with a divine spirit of skill, ability and knowledge…” (Exodus 31:3). This is also extended to the craftsmen Bezalel employs: “…and I have also granted wisdom to all who are wise that they may make everything that I have commanded…” (Exodus 31: 6). This gift is far above skill and talent. The Hebrew uses the expression hakham lev, literally “heart-knowledge,” to describe the spirit imbued in each artisan. Apportioning wisdom is not only from God to humans. In Numbers 11, when Moses struggled mightily with a difficult flock, God apportioned 70 elders with the spirit of Moses’ wisdom: “…I will draw upon the spirit that is in you and put it on them” (Numbers 11:17). Moses needed many others who were like him to be allies in the work of community. Nothing requires more wisdom than managing people well. We open our litany of requests with the desire to know, to perceive, to understand, and to think because these capacities make us distinctly human. Yet our rational minds are in a constant tug-of-war with our irrational desires. We pray that wisdom wins the day.

What is Tisha B’Av

August 9, 2020

Reprinted with permission from My Jewish Learning

Tisha B’Av, the ninth day of the month of Av (which coincides with July and/or August), is the major day of communal mourning in the Jewish Calendar. Although many disasters are said to have befallen the Jews on this day, the major commemoration is of the destruction of the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem, in 586 B.C.E. and 70 C.E., respectively. Fasting is central to this day. Although the exact date of the destruction of each of the Temples, the ancient centers of Jewish life and practice, is unknown, tradition dates the events to Tisha B’Av. The rabbis of the Talmudic age claimed that God ordained this day as a day of disaster, as punishment for the lack of faith shown by the Israelites during their desert wanderings after the exodus from Egypt. Over the course of the centuries, multiple tragedies have clustered around this day, from the expulsions of the Jews from England and Spain to more localized disasters. Tisha B’Av is thus observed as a day of communal mourning, expressed by fasting and abstaining from pleasurable activities and diversions. A literature of dirges for this day of mourning has been created, beginning with the biblical Book of Lamentations on the destruction of the First Temple.

A three-week period of low-level mourning leads up to the holiday of Tisha B’Av; the three weeks commemorate the final siege of Jerusalem that led to the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 C.E. It is traditional to refrain from public celebrations, such as weddings, and to refrain from shaving, as is done during personal mourning. The last nine days of these weeks culminating in Tisha B’Av are a deeper period of mourning. It is appropriate to avoid eating meat; some who did not previously take on certain aspects of mourning, such as refraining from shaving, will assume these signs of mourning during these nine days. Tisha B’Av is a day of intense mourning, similar to Yom Kippur in many respects. It is a day of fasting, and a day to refrain from washing, sexual activity, using perfume and ointments, and wearing leather. The Book of Lamentations, Megillat Eicha, and other dirges, kinot, are read in the synagogue. Visits to places of mourning, such as cemeteries, reflect the mood of the day, which continues even at the break fast meal at the conclusion of Tisha B’Av, when neither meat nor wines are consumed.