Jewish History

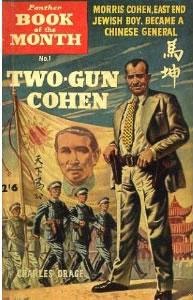

The Story of Moses “Two Gun” Cohen

By Sid Goldstein

Morris Abraham Cohen (1887–1970), better known by the nickname “Two-Gun” was a Polish-born British and Canadian adventurer who became aide-de-camp to Sun Yat-Sen and a General in the Chinese Revolutionary army. Cohen was born in Radzanów, Poland on 3 August 1887. His father was Josef Leib Mialczyn, a wheelwright, and his mother was Sheindel Lipshitz. In 1889 the family emigrated to England and settled in the East End of London, where Josef worked in a textile factory. They changed their family name to the easier-to-pronounce Cohen, and young Moishe became Morris. In April 1900, Morris was arrested as “a person suspected of attempting to pick pockets.” A magistrate sent him to the Hayes Industrial School, an institution set up to care for and train wayward Jewish lads. When he was released in 1905, Cohen’s parents shipped the young Morris off to western Canada with the hope that the new world would reform his ways.

Morris Abraham Cohen (1887–1970), better known by the nickname “Two-Gun” was a Polish-born British and Canadian adventurer who became aide-de-camp to Sun Yat-Sen and a General in the Chinese Revolutionary army. Cohen was born in Radzanów, Poland on 3 August 1887. His father was Josef Leib Mialczyn, a wheelwright, and his mother was Sheindel Lipshitz. In 1889 the family emigrated to England and settled in the East End of London, where Josef worked in a textile factory. They changed their family name to the easier-to-pronounce Cohen, and young Moishe became Morris. In April 1900, Morris was arrested as “a person suspected of attempting to pick pockets.” A magistrate sent him to the Hayes Industrial School, an institution set up to care for and train wayward Jewish lads. When he was released in 1905, Cohen’s parents shipped the young Morris off to western Canada with the hope that the new world would reform his ways.

Cohen initially worked on a farm near Whitewood, Saskatchewan. He tilled the land, tended the livestock and learned to shoot a gun and play cards. He did that for a year, and then started wandering through the Western provinces, making a living as a carnival barker, gambler, railroad worker and farm hand. Cohen also became friendly with some of the Chinese exiles who had come to work on the Canadian Pacific Railroad. In Saskatoon, he came to the aid of a Chinese restaurant owner who was being robbed. Cohen’s training in the alleyways of London came in handy. He knocked out the thief and tossed him out into the street. Such an act was unheard of at the time, as few white men ever came to the aid of the Chinese. The Chinese welcomed Cohen into their fold and eventually invited him to join the Tongmenghui, Sun Yat-Sen’s anti-Manchu dynasty secret society.

It was in pre-World War I Edmonton where Cohen commenced his long and varied military career by recruiting members of the Chinese community and training them in drill and musketry on behalf of Sun Yat-Sen’s organization in Canada. Cohen fought with Canadian Troops in Europe during World War I. He saw some fierce fighting at the Western Front, especially during the Third Battle of Ypres. After the war, he resettled in Canada. But the economy had declined, and he was scuffling.

In 1922 Cohen headed to China. After disembarking in Shanghai, he met with George Sokolsky, the New-York journalist who worked for Sun Tat-Sen’s English-language Shanghai Gazette. Sokolsky arranged an interview for him with Eugene Chen, Sun’s Secretary. Cohen was hired as a bodyguard and soon ensconced himself at Sun’s home in the city’s French Concession. In Shanghai, Cohen trained Sun’s small armed forces to box and shoot. He told people that he was an acting colonel in Sun Yat-Sen’s army. Fortunately for Cohen, his lack of proficiency in Chinese — he spoke a pidgin form of Cantonese at best — was not a problem since Sun, his wife Soong Ching-ling and many of their associates were western-educated and spoke English. Cohen’s colleagues started calling him Mā Kūn, and he soon became one of Sun’s main protectors, shadowing the Chinese leader to conferences and war zones.

After one battle where he was nicked by a bullet, Cohen started carrying a second gun. The western community was intrigued by Sun’s Canadian gun-toting protector and began calling him “Two-Gun Cohen.” The name stuck. Sun died of cancer in 1925, and Cohen went to work for a series of Southern Chinese Kuomintang leaders, including Sun’s brother-in-law, the banker T.V. Soong. He was also acquainted with Chiang Kai-shek, whom he knew from when Chiang was commandant of the Whampoa Military Academy. Cohen acted as security for many warlords and ran guns as well. Eventually he earned the rank of acting general in the Kuomintang Army, though he never led any troops. When the Japanese invaded China in 1937, Cohen eagerly joined the fight. He ran guns for the Chinese and did work for the British intelligence agency, Special Operations Executive (SOE), reporting on the positions of Japanese troops. Cohen was in Hong Kong when the Japanese attacked in December 1941. He placed Soong Ching-ling and her sister Ai-ling onto one of the last planes out of the British colony. Cohen stayed behind to fight, and when Hong Kong fell later that month, the Japanese imprisoned him at Stanley Prison Camp. The Japanese badly beat him and he languished in Stanley until he was part of a rare prisoner exchange in late 1943.

In 1947, Cohen sailed back to Canada, settled in Montreal and married Judith Clark, who ran a successful women’s boutique. He made regular visits back to China with the hope of establishing work or business ties. Mostly, though, Cohen saw old friends, sat in hotel lobbies and spun tales. It was his own myth making, together with the desire of others to fabricate yarns about him, that has resulted in much of the misinformation about Cohen, making him somewhat more heroic than he actually was. In 1947, when the newly formed United Nations began the debate on the UN Resolution on the partition of Palestine, following the UN Special Committee on Palestine recommendation, Morris Cohen flew to San Francisco and convinced the head of the Chinese delegation to abstain from voting when he learned they planned to oppose partition. After the 1949 Communist takeover, Cohen was one of the few people who was able to move between Taiwan and mainland China. His prolonged absences took a toll on his marriage, and he and Judith divorced in 1957.

Following his divorce, Cohen settled with his widowed sister, Leah Cooper, in Salford, England. There he was surrounded by siblings, nephews and nieces and became a beloved family patriarch. His standing as a loyal aide to Sun Yat-Sen helped him maintain good relations with both Kuomintang and Chinese Communist leaders, and he soon was able to arrange a consulting job with Rolls-Royce, where he helped procure engines for the Chinese government in Beijing. His last visit to China was in 1965 as an honored guest of Zhou Enlai, whom he had known since the 1920’s. Morris Cohen died in 1970 in Salford, England. He is buried in Blackley Jewish Cemetery in Manchester.

A Famous Jew You Never Knew

January 13, 2021

Waldemar Mordechai Haffkine

BBC via Dina Yoshimi

For those who are winding down for the semester, and those who just enjoy an interesting read:

Here’s a piece from the BBC about Waldemar Mordechai Haffkine, a Jew who made a huge difference in the world of saving lives by vaccine. A timely read in our pandemic times, and a reminder of how fortunate we are for the times we live in. Hats off to historic hero!

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-55050012?utm_source=pocket-newtab

We Are All Jews

November 3, 2020

From The Accidental Talmudist

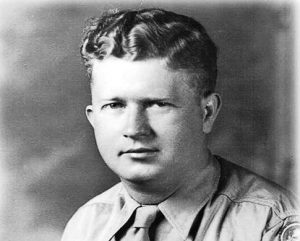

Roddie Edmonds was a U.S. Army Master Sergeant who put his life on the line in a German POW camp to protect the Jewish soldiers under his command. Roddie was a devout Christian from Tennessee who enlisted in the army in 1941 and was sent overseas. In 1944 he fought at the Battle of the Bulge, the last major German offensive campaign of the war. At that battle, Roddie and over a thousand of his men were captured and sent to a German POW camp, Stalag IX-A. In the camp, he was the senior non-commissioned officer and was responsible for 1275 American POWs. On their first day at Stalag IX-A, the German commandant told Roddie that the next morning, all the Jewish soldiers should assemble outside their barracks. Roddie had heard rumors that European Jews were being sent to death camps, and he was determined to protect the Jewish servicemen under his command. Instead of following the Nazi’s orders, Roddie issued his own: ALL 1275 American POWs would assemble outside the barracks in the morning.

The next day, when the Nazi officer saw that all the soldiers were outside, he angrily demanded that Roddie identify the Jews. Roddie told his men that they would not obey the order. Then he turned to the commander and said, “We are all Jews here.” Furious, the Nazi officer took out his pistol and threatened to shoot Roddie. “They cannot all be Jews!” he said, insisting again that Roddie identify the Jewish soldiers. Even with a gun to his head, Roddie did not back down. “WE ARE ALL JEWS,” he repeated. “If you shoot me, you’ll have to shoot all of us and after the war, you’ll be tried for war crimes.” The Nazi backed down and the 200 Jewish soldiers in the group remained with their comrades until they were liberated.

Incredibly, Roddie never told anybody about his wartime heroism. It wasn’t until long after Roddie’s death in 1985 that the story came out. His children, curious about their father’s wartime experiences, started reading the diary he’d kept in Stalag IX-A. Mostly it contained the names and addresses of the soldiers under his command. Roddie’s son Chris started searching the names online and found an old article about Lester Tanner, who became a prominent lawyer in New York. In the article, Tanner said that he and many other Jewish soldiers owed their lives to Sergeant Roddie Edmonds. Amazed, Chris contacted other soldiers from Roddie’s unit, and pieced together the story of his father’s stubborn heroism in Stalag IX-A. In 2015, Roddie Edmonds was honored by the Israeli Holocaust Memorial Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations. 26,000 non-Jews who saved Jews during the Holocaust have been so honored, but Sgt. Roddie Edmonds is the only U.S. serviceman on that list. For bravely defying the orders of a Nazi officer to protect the Jewish soldiers in his care, we honor Master Sergeant Roddie Edmonds as a Hero. (Visit www.accidentaltalmudist.org.)

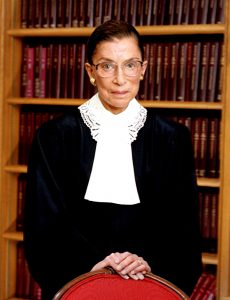

Ruth Bader Ginsburg: A Life Well Lived

October 2, 2020

By Sid Goldstein

RB_Ginsburg_1977_©Lynn_Gilbert

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg died on September 18, 2020. She was arguably, the most important Jewish supreme court justice since Felix Frankfurter. Judge Ginsberg lived an extraordinary life. In her roles as both a litigator and a judge, she left an indelible mark on the American legal system. She was born in Brooklyn, New York in 1933. She married Martin D. Ginsburg in 1954. She received her B.A. from Cornell University, attended Harvard Law School, and received her LL.B. from Columbia Law School where she graduated first in her class. Nonetheless, she received no offers from law firms upon her graduation from Columbia. She said “I had two strikes against me. I was a woman and I was a Jew.” So Ruth became a teacher instead. She worked at Rutgers, Columbia and Stanford. In 1971, she was instrumental in launching the Women’s Rights Project of the American Civil Liberties Union. This work resulted in her being hired as the General Council for the ACLU in 1973. During the early and mid-seventies, she litigated several highly publicized cases that helped reshape American jurisprudence. Reed v. Reed, for instance, dealt with an Idaho law that gave preference to a father over a mother in administering their late son’s estate. The case established women’s rights to manage the financial affairs of their own families. In some states, prior to this case, women were not even allowed to have independent checking accounts without their husband’s permission. Ginsburg advocated for Susan Struck (Struck v. Secretary of Defense), who had been told she needed to terminate her pregnancy if she wanted to stay in the Air Force–clearly an issue a man would never face.

The courts decided that such gender inequality in the military services was not sustainable. This was a landmark decision that opened the road to a far greater role for women in the US military services. In all, Ginsburg litigated six major cases before the US Supreme court and won five of them. In 1980, President Jimmy Carter selected her for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. Thirteen years later, with the retirement of Justice Byron White, President Bill Clinton had the opportunity to appoint a Supreme Court justice for the first time and selected Ginsburg. She was confirmed by the US Senate on a vote of 96-3. Ginsburg was only the second woman, after Sandra Day O’Connor, to serve on the Supreme Court. In her 27 years on the court, she was an unfailing advocate for human rights. She protected, as is called out in the Torah “the widow the orphan and the hungry.” In 1996, she wrote a strong majority opinion in the case of the Virginia Military Institute which had a male only admission policy. She wrote, “many women would not want to go to VMI, but many men would not, either. And as long as there are qualified women who want to go — and there are — they must be admitted.” Another landmark decision. In her later years, Justice Ginsburg became a cultural icon.

After the publication of the book The Notorious RBG, Ginsburg became a symbol of achievement and promise to young women all over the world. It was a remarkable testament to the life work of a small, shy Jewish lawyer, that she could become known as a symbol of human rights to so many. It will be some time before we see her like again.

After the publication of the book The Notorious RBG, Ginsburg became a symbol of achievement and promise to young women all over the world. It was a remarkable testament to the life work of a small, shy Jewish lawyer, that she could become known as a symbol of human rights to so many. It will be some time before we see her like again.

Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz Has Passed Away (Baruch Dayan Emet)

September 3, 2020

By Dina Yoshimi

Our people have lost a great scholar, and a man who made the Talmud accessible to many current generations. Here’s a link to the obituary in the Jerusalem Post:

https://www.jpost.com/breaking-news/noted-talmudic-scholar-rabbi-adin-steinsaltz-dies-aged-83-637828

A Tribute to Carl Reiner

August 19, 2020

By Sid Goldstein

Carl Reiner

One of the great paragons of American humor died on June 30. Carl Reiner was a prolific writer, director, producer, and actor. His career spanned almost 75 years in show business. Reiner once said of his career, “I taught gentiles a lot about Jewish humor.” He first came into prominence as a writer, and later as a cast member of Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows. Reiner began as a straight man for Caesar and his costar Imogene Coca. He was a part of what is now considered the greatest collection of comedy writers ever assembled. Sid Caesar hired Woody Allen, Neil Simon and Larry Gelbart as well as Reiner, Danny Simon, and Mel Brooks. Neil Simon’s play Laughter on the 23rd Floor is a tribute to this renowned staff of comedy geniuses.

After the Caesar show, Carl Reiner and Mel Brooks produced the smash comedy record album, The 2,000-Year-Old Man. The album was heavily reliant on Jewish humor, using a lot of Yiddish expressions and some very old Jewish jokes. (“I have 1500 children. They never write and they never call. You’d think at least one could afford long distance.”) Reiner struck comic gold on television when he created The Dick Van Dyke Show. He took his Sid Caesar experience and made Rob Petrie (Dick Van Dyke) the head writer of a TV comedy show. He later played the egotistical star of the Show, Alan Brady. Reiner is also credited with hiring a very young, and largely unknown Mary Tyler Moore for the role of Laura Petrie, Rob’s wife. The Van Dyke Show was a top-10 rated show for most of its six-year run. It is still considered one of the best and most beloved comedy TV shows ever produced.

Reiner kept working after the Van Dyke show. He wrote and directed Steve Martin’s debut film The Jerk. He teamed up with Martin again for a detective satire Dead Men Don’t Wear Plaid. Both films were box office successes and helped launch Steve Martin as a major star. Reiner directed several hit comedy films in the 1970s and 80s. These included: Where’s Poppa with George Segal, Oh God!, with George Burns, Summer Rental with John Candy and That Old Feeling with Bette Midler. In the 90’s Reiner did some TV guest shots. He had a recurring role on Mad About You and wrote and directed an episode of Frazier at the request of Kelsey Grammer. He even showed up on an Episode of Two and Half Men in the early 2000s. Reiner’s last great set of films were the George Clooney Oceans trio. Reiner appeared as con man Saul Bloom in all three of the films. His bits, particularly his “German Count’s” insistence on seeing the vault in Ocean’s Eleven, were considered some of the high points of the three films.

Carl Reiner lived to be 98 years old. He spent 65 years married to the same woman and raised a large family – including his well-known son Rob Reiner, who blazed his own show business trail. Carl Reiner brought joy to many and will be remembered as an all-time great in the long litany of Jewish-American comics.

Rob (left) and Carl (right) Reiner

Jews and Social Distancing

May 25, 2020

By Dr. Daniel Meckler, New York University

The email a few weeks ago that let me know that I was under a nine-day quarantine induced one of the deeper stomach-drops of my admittedly cushy life. It galled me that, of all the high schools in all the towns in all the world, the coronavirus walked into mine.

That I was seemingly spared from the virus itself; that not going into work didn’t threaten my ability to pay rent or put food on the table; that, as a young Manhattanite beneficiary of various axes of privilege, I am unprecedentedly, historically free even in quarantine: All those only made me slower to comprehend that I suddenly wasn’t allowed to do whatever I wanted. It was Purim, and what I wanted was mainly to celebrate a raucous holiday with friends. Instead, I found myself alone in my room, gamely dressed up as a frog, listening to the Megillah trip in electronically through my computer speakers. The next day, I ate a quiet festive meal with the roommates. All the while I felt a dull tug toward the ceremonies as I’d envisioned them in the anticipatory weeks before Purim, communal and crowded and in Technicolor.

But consolation wasn’t late in coming, I’m an aspiring student of modern Jewish philosophy, so much of which is cast as the happy breakthrough of the individual from the confines of community. Social isolation is a theme at the root of both our present coronavirus situation and the early birth pangs of Jewish modernity. Despite the deeply communal nature of Jewish religion, Jewish philosophers were forced by circumstance to engage with Judaism as an individualistic exercise. Within a strand of modern Jewish philosophy’s wide tapestry, we find lonely Jews thinking lonely thoughts.

While Jewish legal decisions throughout history had no choice but to root themselves in religious communities and depend on their consent, many modern Jewish philosophers did their thinking alone. Spinoza was a heretic cut off from his community. Less sympathetically, Salomon Maimon abandoned not only his hometown but a wife and children to chase philosophical truth. Nachman Krochmal taught secretly in the rural hills of Galicia before rushing (and failing) to complete his book before his death. The earliest ones to put modern philosophy in conversation with Jewish texts were largely self-taught and often socially isolated, beyond the bounds of normative Jewish communities.

In an earlier age, or even a different community today, my quarantine could have been a great chance to secretly read up on a Jewish Index of Forbidden Books. Regrettably, I’ve never needed to hide German philosophy under my pillow, or stash works of biblical criticism behind big books of classical commentary. My local Jewish community—my synagogue and the high school where I work—has wide intellectual horizons. There is no divide between the people I daven with and the people I talk to; they are the same collection of eccentric Jews. Cut off from these conversation partners, my quarantine is what was intellectually confining. On my better days, the video chats I got from caring friends helped tide me over and lessen the annoyance of quarantine. At other times, communicating virtually dropped into the uncanny valley of Jewish communal interaction. The effortful, flat nature of connecting over the computer made me more intensely miss the warm serendipity of the real thing. I’ve never felt suffocated by my community, as Spinoza may have been by his, but I was too many days into this quarantine, and I missed being swaddled.

Beyond the persona of the lone, heroic, modern Jewish philosopher, strands in modern Jewish thought itself have established individual experience as the basic unit of Jewish religiosity. This shift was inaugurated by Moses Mendelssohn in the 18th century. In the Protestant West, there was active pressure to downplay the communal nature of Judaism and express it in terms of personal faith, the better to assimilate into hostile Christian society. This strand stayed strong throughout the 20th century, whose existential turn again focused on personal religious faith. Joseph Soloveitchik, though firmly established in Jewish community, emphasized autonomy and individuality. He explored the possibilities of the unfettered modern man and spilled more ink on the religious tensions within the human psyche than on those between people in community. While Jewish modernity is an enduringly communal enterprise, it has so much individualism in its intellectual foundations.

And so, by the lights of some of Jewish modernity’s greatest thinkers, my quarantined Purim should have been a ladder to certain kinds of new spiritual heights, my isolation an opportunity for white-knuckled, religious existential encounter. It wasn’t. Religious experience, I strongly believe, is something that happens in a community. Instead, my quarantine saw me flit between Netflix and a novel, periodically munching the chocolate cookies my roommate was good enough to pick up for me. As I idled away the hours, I thought of Purim, the holiday that lives in the space between a reader and a listener of the Megillah, within the giving of gifts to the poor, amid the chatter of a packed festive feast. The lone Jew on Purim is left to serve a God who, as in the Book of Esther, is frustratingly obscured from view.

At the time, I was rare for having been in quarantine. Sadly, many more others soon joined me. Religious Jews have succeeded in creating robust communities in a modern-day America where community can be hard to come by. Judaism will survive this, too, as it has so much in the past. And our central concern moving forward should be with those for whom COVID-19 acutely threatens their health and livelihood. But in the doldrum hours of this quarantine, going a little stir-crazy, kept company by my own mind and by the Jewish philosophical canon arranged in messy piles, I bumped up against the stark limitations of being Jewish alone.

In her recent work The Obligated Self, Jewish philosopher Mara Benjamin reacts against the individualistic thrust of modern Jewish thought, instead positing a vision of Jewish freedom grounded in dependency, community, and physical interaction. She captures the constant, interdependent nature of Jewish ritual by analogizing it to a mother’s care for a child. We should be clear-eyed about the fact that if Judaism is so intensely social, a Judaism that must navigate the social distancing imposed by coronavirus will be intensely diminished.

The isolation of the first modern Jewish philosophers was born of communal scorn; our present isolation is a mark of communal care, even as it pushes us further apart. And amid this pandemic, by necessity more than by choice, I have been pushed to think through the enduring power of Jewish philosophical traditions that before I would have described as individualistic to a fault. Now is as good a time as ever to newly explore Jewish productivity and spirituality in isolation. To be sure, loneliness isn’t the only Jewish philosophical lens relevant right now. One could just as easily connect our situation to themes of care, family, and healing, among others. But there is undoubtedly loneliness ahead, and the isolationist trend within modern Jewish thought should be appropriated as a resource to get us through.