Sof Drashes 2024

From Folk Tales, History

January 2024

Parasha Miketz Drash by Robert J. Littman

The Torah is a sacred history of the Jewish people from the patriarch Abraham down through the death of Moses. It is a family history of the descendants of Abraham that recounts the encounter of the children of Israel with the divine during this period. It is the story of a patrilineal kinship group, that is a descent of all members from a common ancestor, Abraham, either through birth or adoption. As such, it follows a similar pattern of sacred histories of many cultures over many eras and geographical locations. The sacred history continues down another 1200 years in the Prophets, and Writings. Sacred history is true, but not always factual. When we get to the later periods of Jewish history, such as the story of the Maccabees, we can often see the seams where sacred history developed. One example is the “miracle” of Hanukkah. The Maccabees led a revolt against the Greek monarch, Antiochus Epiphanes, ruler of the Seleucid kingdom. In 164 BCE Judah Maccabee reconquered Jerusalem and purified the Temple. The Talmud and the Megillah of Antiochus, written at least 500 years after the event, tell us that the Maccabees found pure oil which would only last for one day, but miraculously, the oil lasted for eight days. However, when we read the Book of Maccabees, likely written by a Maccabean court historian in the late 2nd century BCE, we find the story of the purification of the Temple, but no mention of the story of the oil lasting eight days. The “miracle” of 8 days of oil was made up hundreds of years later to give a religious interpretation to the festival of Hanukkah, which had hitherto been a celebration of the independence day of the Maccabees. For the Maccabees the real miracle of Hanukkah was that a small rebel force had defeated a mighty empire and established an independent kingdom. For Talmudic Judaism a military victory was not the miracle, but the miracle was a new story, that the purified oil lasted eight days. So, if we look at the story of Joseph, was Joseph a real figure, and if so, are the stories about him based in fact or folklore? There have been many attempts to place Joseph in Egyptian history. But in fact, there is no mention of Joseph, nothing in Egyptian sources that indicate he ever lived. Many of the elements of the story are drawn from folk tales that are found in many ages and places. The story of the wife trying to seduce someone in the household, and then rejected, is found in many cultures. We find almost the same story in Greek myth. Phaedra, the wife of King Theseus, tried to seduce her stepson, Hippolytus, but was rebuffed. In fear of discovery, she wrongly accused Hippolytus of trying to seduce her. Likewise, in ancient Egyptian folklore, the wife of Anpu tries to seduce Anpu’s brother, Bata, and when rebuffed, accuses Bata of trying to seduce her. The story of the Seven Year famine may be based on a historical occurrence of famine. A stone stele, inscribed on Sehel island in the Nile near Aswan, Egypt, describes a seven year drought and famine in the reign of the pharaoh Djoser around 2650 BCE because the Nile failed to flood. Djoser asks the priest, Imhotep, for help in solving the famine. Imhotep travels to Hermopolis to consult the god Khnum. Imhotep falls asleep and is advised in a dream by the god Khnum. Imhotep reports this visitation of the god to Djoser, who restores the temple of Khnum, and Djoser grants the temple of Khnum power over the region around Aswan, and a share of all imports from Nubia. Imhotep rises to be one of the most important people in Egypt after Djoser. The story of Joseph is also a connective device to explain the double origins of the Israelites, one branch the descendants of Abraham, and the other the Israelites living in Egypt with Moses. Joseph’s story tells how the Israelites came to Egypt, and how Moses was really a descendant of Abraham. Many elements of the Joseph story reflect actual Egyptian material: accounts of mummification of Jacob, mummification of Joseph, marriage with Egyptian women. Various attempts have been made to identify Joseph with historical Egyptians. One, is that he is really Yuya, a probable Semite, who was the grandfather of Tutankamun. While this identification is improbable, we do know of a Semite, named Aper-El who rose to become an official of the pharaoh Amenhotep III (1400-1353 BCE). The mummy and tomb of Aper-El, whose name probably means, “servant of El,” survive. If the story of Joseph simply is a folk-tale, how do we treat it in the context of sacred history? It does not matter whether the story of Joseph, or the other stories are true. The stories explain who the Jewish people are and their encounter with the divine. The Jewish people existed in the late 2nd millennium BCE, and we are members of their kinship group, whether by descent or adoption. What is important is the message of that encounter, the basis of our laws and our history. Think of the events like a painting- the artist completes the painting which is his vision of events. By its very nature it is an interpretation of reality. Subsequent viewers participate in the artist’s vision of reality but can bring their own biases and life experiences to draw out of the picture their own meaning. That is why every generation interprets the sacred text and history in line with their own societal biases and structures. It is a divine revelation through our interpretation of it and the ability of each age to find the divine in the narrative. The artist’s original interpretation is superseded by that of every viewer.

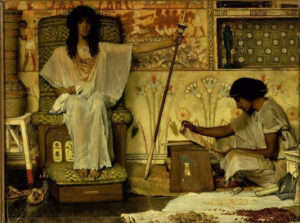

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema Joseph, Overseer of Pharaoh’s Granaries (1874)

Forgiving Our Brothers

January 2024

Vayehi Drash by Stan Satz

Va-y’hi: Gen. (47:28-50:26) In Chapter 50, after Jacob, the last of the Patriarchs, dies, Joseph’s brothers are terrified that Joseph will now severely punish them for conspiring to vengefully and treacherously entomb him in a desert pit to either rot away or be enslaved. “What if Joseph still bears a grudge against us and pays us back for all the wrong that we did him?” Initially afraid to face Joseph directly, the brothers (perhaps waiting nearby) either have someone else deliver a last-minute message from Jacob to Joseph, or they do so themselves as they cautiously approach him: “before his death, your father left this instruction. ’Forgive, I urge you, the offense and the guilt of your brothers who have treated you so harshly. Therefore, please forgive the offense of the servants of the God of your father.’ And Joseph was in tears.” The brothers, awed by his apparent breakdown, now tentatively come even closer to Joseph while he is still weeping. (verses 15-18) Many ancient and modern biblical scholars have pointed out the abundant ambiguity in these verses. Textually, there is no indication that Jacob pleaded with or commanded his sons to tell Joseph that he should be merciful towards them. Should we believe the brothers, or did they manufacture this self-serving smokescreen to ingratiate themselves with Joseph, who now that Jacob has died, might well be planning to execute his brothers for their loathsome betrayal? Nor do we know if Joseph fully believes Jacob’s alleged deathbed testament. In fact, Joseph might be weeping because he laments that his brothers have concocted such a scenario, a scam that exploits their father and insults Joseph’s intelligence. On the other hand, Joseph may have spontaneously sobbed because he was so relieved that Jacob devoutly wanted to erase any residual enmity that Joseph had for his brothers. In any case, whether or not Joseph believes their account, the brothers go one step further by displaying their devotion to Joseph: “They flung themselves before him and said, ‘We are prepared to be your slaves’” (verse 18). If the brothers had any doubts about Joseph’s stance, verses 19 to 21 indicate that they no longer have to anxiously anticipate Joseph’s justified wrath. Joseph will always protect them (if not cherish them), even though they once sought to dispose of him. “Although you intended me harm, God intended it for good, so as to bring about the present result—the survival of many people. And so, fear not. I will sustain you and your children. Thus he reassured them, speaking kindly to them.” Even if the brothers concocted a story about their father’s wanting Joseph to spare them, the result is a blessing, according to this legendary Talmudic commentary: “Great is peace, for even the tribal ancestors resorted to a fabrication in order to make peace between Joseph and themselves” (Midrash 59). The revenge and reconciliation motif reminds me of my relationship with my younger brother. I was living in New Bern, North Carolina, when my aging and ailing parents moved nearby. My brother was sequestered in Albuquerque. Up to that time, my brother and I were always gracious to each other. Within a few months, my father developed a slew of afflictions: Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, dementia, emasculating prostate cancer and bone cancer. My health worsened as well: I was beset with liver abnormalities, an ulcer, and intermittent back spasms. When I told my brother about the anxieties that I had with our father’s deepening deterioration and my own physical problems, he didn’t offer me any support. His indifference infuriated me. I solely had the burden of caring for my father and watching him degenerate. Maybe my brother felt that I deserved the misery enveloping me. After all, for years, my father favored me more than he did my brother. Nonetheless, I stewed in my resentment. Soon, I got my revenge. My brother’s son was to have his bar-mitzvah in a few months. My parents and I were invited. Of course, my father, who was now in a nursing home, was too ill to attend. My mother implored me to fly with her to Albuquerque for the ceremony. I, ensconced in my hurt feelings, steadfastly refused to go. My partly valid excuse was that I couldn’t leave my father in his godforsaken decline. Actually, I stayed home so that I wouldn’t have to confront my disloyal, heartless brother. When my mother died soon afterward, my brother came to the funeral. I was apprehensive about our ensuing encounter, fearing that I might or he might become combative; but things went pretty smoothly: We politely exchanged commiserations. I suppressed my animosity towards my brother, and if he had any against me, he didn’t reveal it. When our father died a few months later, my brother did not come to the funeral. What an affront to me and my deceased dad! Was my brother paying me back for not attending his son’s bar-mitzvah? Was this his revenge? I was devastated. He didn’t even send a sympathy card. However, two weeks after the funeral, my brother phoned me. He seemed contrite, but I had no use for his belated concern. I scorned his reaching out to me. How could he make up for those years of ignoring the agony that our father and I had to endure? With my wife’s encouragement, I frequently saw a counselor to help me contend with my anger towards my brother. At the last session, as I began to relate how close my brother and I once were when we were kids, I started to cry. And when I further recounted that when my brother got a bit older, he thwarted my affection, never mind my attention, I wept some more. I was surprised that I got so emotional. I guess I missed my brother more than I’d like to admit. Then I reflected on how self-righteously critical of him I have been ever since he distanced himself from our father and from me. Perhaps I was responsible for poisoning our relationship. Then I began to dredge up all the instances in which I gave my brother such a hard time: for driving barefoot, or for preferring dissonant modern classical composers to the melodies of the romantic titans, or for hanging out with our sketchy iconoclastic cousin, who my father and I felt was a bad influence. How petty I was. That last counseling session was quite an epiphany. No longer enraged against my brother, I regularly phoned him about my incredibly enriching life in Honolulu, and he warmly shared his delight in Albuquerque. We began to be truly engaged with each other. A few years ago, we consolidated our camaraderie: I went to my brother’s grandson’s bar-mitzvah in Albuquerque. At first, shaking each other’s hands was the extent of the developing trust between my brother and me. A couple of days after the affair, just as I was getting into the rental car to leave for the airport, my brother bounded out of his house, evidently to wish me a safe trip. Instead, he embraced me for the first time during our visit. Overwhelmed by his unexpected and much appreciated gesture, I gladly reciprocated. Recently, I again visited my brother in Albuquerque. This time, there were hugs galore, and he even fixed my favorite dish, slabs of salmon. Now that’s true affection. As with Joseph and his brothers, there are many threads in the saga between my brother and me; but the most life-enhancing ones transform bitter revenge into sweet reconciliation. As we approach 2024 in a couple of days, let us look forward towards forgiving people (especially family and friends) who we feel have slighted or demeaned us in the past. Such a reassessment (however painful) would be a blessing. Amen.

Star Wars Edition

May 2024

Acharei Mot Drash by Jake Honigman

With Pesach now over, it’s time to talk about . . . Yom Kippur! That’s right, this parshah we just read, Acharei Mot – in addition to giving us the rules on incest, some controversial stuff about men lying, and some additional kashrut rules, talks a lot about Yom Kippur. The portion of Acharei Mot regarding Yom Kippur – which is actually also the Torah reading on Yom Kippur (during morning service) – is the place in the Torah where Hashem defines Yom Kippur, and commands us to observe it. So I want to talk a little bit about Yom Kippur. First I’m going to talk about how we observe Yom Kippur, about our modern understanding of what Yom Kippur is about. Then I’m going to talk about what Acharei Mot actually says about Yom Kippur. And then, I’m going to talk about Star Wars. (Today being May the 4th . . ). We all know that Yom Kippur is about atoning for our sins, so that we may be sealed in the Book of Life. But atoning how? Our modern understanding is based largely on T’shuvah. Returning. Repentance. Recognizing our sins, our misdeeds. Confessing them. Apologizing for them. Committing to doing differently, and better. Starting in the month of Elul, we repent. We say selichot. We blow the shofar. We ask for forgiveness. Then, as Tishrei begins and we pass Rosh Hashanah, we enter the Aseret y’may t’shuvah. The 10 days of t’shuvah. The shabbat during the Aseret y’may t’shuvah – the shabbat before Yom Kippur – is Shabbat Shuvah. Shabbat of return! In the haftarah for Shabbat Shuvah (my bar mitzvah haftarah), we read from Hoshea: שׁוּבָה יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל עַ֖ד יְהֹוָ֣ה אֱלֹהֶ֑יךָ כִּ֥י כָשַׁ֖לְתָּ בַּֽעֲוֹנֶֽךָ “Return, O Israel, to the Lord your God, for you have stumbled in your iniquity. Return to the Lord. Say: ‘You shall forgive all iniquity and teach us the good way’” Maimonides, the Rambam, wrote a book called Hilchot Teshuvah – the laws of t’shuvah (part of the Mishneh Torah). He said: “Everyone is obligated to repent and confess on Yom Kippur. The mitzvah of the confession of Yom Kippur begins on the day’s eve, before one eats [the pre-Yom Kippur meal. And] even though a person confessed before eating, [he must] confess again in the evening service, Yom Kippur night, and repeat the confession in the morning, Musaf, afternoon, and Ne’ilah services.” Rabbi Heschel – in a 1965 essay called “Remarks on Yom Kippur” – wrote: “We are all failures. At least one day a year we should recognize it.” And of course, our Yom Kippur services do indeed feature a ton of confessing, discussing our wrongdoings, and asking forgiveness – al chet, vidui, again and again, and more. So now let’s take a look at the Torah portion. Now I want you all to listen carefully, and I’m going to read directly from the Torah – from the English translation – and I want you to see how much you hear about recognizing sins, talking about them, apologizing for them. OK, ready?

- With this shall Aaron enter the Holy: with a young bull for a sin offering and a ram for a burnt offering.

- He shall wear a holy linen shirt and linen pants shall be upon his flesh, and he shall gird himself with a linen sash and wear a linen cap these are holy garments, [and therefore,] he shall immerse himself in water and don them.

- And from the community of the children of Israel, he shall take two he goats as a sin offering, and one ram as a burnt offering.

- And Aaron shall bring his sin offering bull, and initiate atonement for himself and for his household.

- And he shall take the two he goats, and place them before the Lord at the entrance to the Tent of Meeting.

- And Aaron shall place lots upon the two he goats: one lot “For the Lord,” and the other lot, “For Azazel.”

- And Aaron shall bring the he goat upon which the lot, “For the Lord,” came up, and designate it as a sin offering.

- And the he goat upon which the lot “For Azazel” came up, shall be placed while still alive, before the Lord, to [initiate] atonement upon it, and to send it away to Azazel, into the desert.

- And Aaron shall bring his sin offering bull, and shall [initiate] atonement for himself and for his household, and he shall [then] slaughter his sin offering bull.

- And he shall take a pan full of burning coals from upon the altar, from before the Lord, and both hands’ full of fine incense, and bring [it] within the dividing curtain.

- And he shall place the incense upon the fire, before the Lord, so that the cloud of the incense shall envelope the ark cover that is over the [tablets of] Testimony, so that he shall not die.

- And he shall take some of the bull’s blood and sprinkle [it] with his index finger on top of the ark cover on the eastern side; and before the ark cover, he shall sprinkle seven times from the blood, with his index finger.

- He shall then slaughter the he goat of the people’s sin offering and bring its blood within the dividing curtain, and he shall do with its blood as he had done with the bull’s blood, and he shall sprinkle it upon the ark cover and before the ark cover.

I’m going to skip two p’sukim here. By the way, if you’re thinking I’m trying to sneak in some extra Torah reading, my response would be: “So?”

- And he shall then go out to the altar that is before the Lord and effect atonement upon it: He shall take some of the bull’s blood and some of the he goat’s blood, and place it on the horns of the altar, around.

- He shall then sprinkle some of the blood upon it with his index finger seven times, and he shall cleanse it and sanctify it of the defilements of the children of Israel.

- And he shall finish effecting atonement for the Holy, the Tent of Meeting, and the altar, and then he shall bring the live he goat.

- And Aaron shall lean both of his hands [forcefully] upon the live he goat’s head and confess upon it all the willful transgressions of the children of Israel, all their rebellions, and all their unintentional sins, and he shall place them on the he goat’s head, and send it off to the desert with a timely man.

So we just heard mention of confessing – I will talk about that in a minute. Let’s continue:

- The he goat shall thus carry upon itself all their sins to a precipitous land, and he shall send off the he goat into the desert.

- And Aaron shall enter the Tent of Meeting and remove the linen garments that he had worn when he came into the Holy, and there, he shall store them away.

- And he shall immerse his flesh in a holy place and don his garments. He shall then go out and sacrifice his burnt offering and the people’s burnt offering, and he shall effect atonement for himself and for the people.

- And he shall cause the fat of the sin offering to go up in smoke upon the altar.

- And the person who sent off the he goat to Azazel, shall immerse his garments and immerse his flesh in water. And after this, he may come into the camp.

- And the sin offering bull and he goat of the sin offering, [both of] whose blood was brought to effect atonement in the Holy, he shall take outside the camp, and they shall burn in fire their hides, their flesh, and their waste.

- And the person who burns them shall immerse his garments and immerse his flesh in water. And after this, he may come into the camp.

- And [all this] shall be as an eternal statute for you; in the seventh month, on the tenth of the month, you shall afflict yourselves, and you shall not do any work neither the native nor the stranger who dwells among you.

So all we get is one mention of “confessing” – and it’s Aharon “confessing” all the sins of all of B’nai Yisrael. To a goat. Aharon doesn’t know, obviously, the sins that each person has committed. He’s not engaging in any kind of sincere apology, to this goat. Sounds to me more like a symbolic transference. There’s nothing requiring each individual Israelite to confess, or discuss, or apologize for his or her sins, or even suggesting that they do so. Nothing remotely close to what we would recognize as t’shuvah. The focus of what the Torah says about Yom Kippur is not on any of that stuff at all. It’s on purification. On cleansing. The focus of what the Torah says about Yom Kippur is not on talking about sins and apologizing for them. It’s about getting cleansed of them – and through symbolism as much as anything else. Ritual and symbolism. And, of course, there still is a strong tradition and culture of cleansing ourselves of sins in a symbolic manner. We conduct the Tashlikh ritual. We cast off bread, and we say: “He will show us compassion, suppress our iniquities, and cast all sins into the depths of the sea.” וְתַשְׁלִיךְ בִמְצֻלוֹת יָם כָּל־חַטֹּאתָם Some Jews, conduct the Kaparot ritual. Rather than really describe it, I’ll just quote the prayer that is said while doing Kaparot: “This is my substitute. This chicken shall go to its death and I will go on to a good long life and to peace.” And actually, speaking of animals going to their death, I should also circle back to what I read a minute ago in the Torah portion about the two goats. You heard me say that the goat to whom Aharon told B’nai Yisrael’s sins (the “Azazel” goat) would be sent off into the desert. But that has been interpreted to involve a fate far more dramatic than simply being sent into the desert, to wander around there. The Mishnah (Yoma Chapter 6) says that the person in charge of sending the goat into the desert actually would “push the goat backward, and it would roll and descend. And before it was even halfway down the mountain, it would be torn limb from limb.” So as part of our Yom Kippur ritual – according to the Mishnah, and accepted widely in Jewish lore – we’re pushing this goat, this scapegoat, off a cliff. We’re having it fall violently to its demise. So now we’ve talked about t’shuva, repentance, recognizing and apologizing for our sins. And we’ve talked about the Torah’s treatment of Yom Kippur, and cleansing ourselves of our sins, symbolically casting them off. I said we were going to talk about Star Wars, so let’s go ahead and do that now. I’m going to keep it old school Star Wars, just the original trilogy. In the first Star Wars movie (Episode IV), the bad guy is Darth Vader. He is ruthless, taking Princess Leia prisoner, destroying her home planet while she watches, killing Obi-Wan Kenobi. The embodiment of evil. Before Obi-Wan dies he tells us a little bit about Darth Vader’s origin, that he used to be good, that he was a young Jedi and a pupil of Obi-Wan’s – who was seduced by the Dark Side, and turned to evil. At the end of the first movie, the rebels (the good guys) manage to destroy the Death Star, but the villain Lord Vader very much lives on just as he is. In the second Star Wars movie, the Empire Strikes Back (Episode V), Darth Vader is still the primary bad guy, but we now meet “the Emperor” – briefly – when we see his holographic, disfigured face talking to Darth Vader. It is he who tells Darth Vader that Luke is Darth Vader’s son, and the two of them discuss turning Luke to the Dark Side. The Emperor is clearly the true source of evil. But Darth Vader is still very much on the evil path, telling the Emperor that Luke “will join us, or die, Master.” Near the end of the movie Darth Vader and Luke engage in extended combat, with Darth Vader using his command of the Dark Side to overpower Luke, enabling him to slice off one of Luke’s hands. Darth Vader then makes an impassioned plea for Luke to join him on the Dark Side, during which he tells Luke he is Luke’s father. Luke, of course, refuses to join the Dark Side, but escapes, and at the end of this movie the stage is set for another showdown. Which brings us to the third and final movie of the original Star Wars trilogy, the Return of the Jedi (Episode VI). At the beginning of this movie, we see Darth Vader arrive on the new Death Star they’re building, and get into a heated exchange with his underlings about the pace of construction. But in this exchange, Darth Vader focuses on the Emperor, and what the Emperor will do to them if they underperform. He ends with telling a commander: “The Emperor is not as forgiving as I am.” A few scenes later, when the Emperor shows up – in person, for the first time – he lays out his plan to turn Luke to the Dark Side, with an evil cackle, while Darth Vader merely says: “As you wish.” Meanwhile, right after Yoda dies, Obi-Wan Kenobi’s spirit comes to talk to Luke. As they start to talk about Darth Vader, Luke tells Obi-Wan (over Obi-Wan’s doubt): “There is still good in him.” Then, when Luke tells Leia that she’s his sister (and also Darth Vader’s daughter), he tells her (over her doubt) that he must confront Darth Vader because “there is good in him. He won’t turn me over to the Emperor. I can save him. I can turn him back to the good side.” By the end of the movie, near the end of the movie, Darth Vader is indeed redeemed. But redeemed how? Darth Vader captures Luke and brings him before the Emperor. Luke defiantly tells the Emperor that he is mistaken about Luke being open to join the Dark Side. The Emperor replies: “You will find that it is you who are mistaken . . . about a great many things.” The exchange continues for a while, with the Emperor epitomizing evil, telling Luke about how Luke’s rebel friends will be unable to save him. We hear the Emperor’s underlings say he “has something special planned” and we watch the Emperor order vicious attacks on the rebel forces, while Luke watches. The Emperor teases and taunts Luke, inviting him: “Strike me down with all of your hatred, and your journey toward the Dark Side will be complete.” Luke and Darth Vader start fighting, while the Emperor sits there, cackling, taunting, as father and son fight viciously. In a lull in the fighting, Luke says to Darth Vader: “I feel the good in you.” So how does it end? Does Darth Vader suddenly declare the evil of his ways, and do t’shuvah? Does he confess, and repent, and apologize? No! The sparring, verbal and physical, continues, as vicious as ever, until Luke slices off one of Darth Vader’s hands! And that moment the Emperor comes down from his perch, laughing of course, and it is the two of them – good is embodied by Luke, and evil is embodied by Emperor Palpatine. When the Emperor’s attempt to get Luke to finish Darth Vader off – to kill him – fails, and Luke declares he will never turn to the Dark Side, the Emperor reveals a new weapon we have never seen before. “If you will not be turned, you will be destroyed.” He starts shooting lightning at Luke, as Luke lies there defenseless. He does so again and again as he taunts Luke, who can do nothing but scream in pain, and beg for Darth Vader’s help. “Now, Young Skywalker, you will die.” More lightning, more horrible screams. Until we hear Darth Vader say: “No. No!” Darth Vader comes up behind the Emperor, and he picks the Emperor up, as lightning pulsates through both of their bodies – to the point that we can even see Darth Vader’s skeleton through his armor and mask. Darth Vader then throws the Emperor down the reactor shaft. We hear the Emperor now screaming, as he pulsates with his own lightning, and when he hits the bottom we see a fantastic explosion. Darth Vader has caused the Emperor, the symbol of evil, to fall violently to his demise. In the final scene between Luke and Darth Vader, his father, Darth Vader lies nearly lifeless, and asks Luke to take off his mask, as he can’t even do so himself. He tells Luke he is going to die. We see Darth Vader’s face, and he tells Luke to leave him and go fight. Luke says: “No, I’ve got to save you.” Unmasked Darth Vader replies: “You already have.” And as he dies, there is doubt that Darth Vader – Anakin – has, indeed, truly been redeemed. And yet he has never confessed, repented for, or apologized for, a single one of his sins. Shabbat shalom, and May the 4th be with you!

Becoming a Sanctuary

March 2024

Pekudei Drash by Rabbi Daniel Lev

In Pekudei, the parsha this week, we learn that Moshe, Oholiav the architect and others finished building the Mishkan – the Moble Temple, also called the Mikdash, the Holy Place, and the Tent of Meeting. Some of you know that Mishkan comes from the Hebrew root Shachan which means “to dwell.” It is the Dwelling Place of HaShem on the earth (at least for the Biblical Yiddin).And now, immediately after it was built, the Presence of the Never Ending One entered and filled it. Before we look at that and its implications for our very lives….let’s look fifteen chapters earlier at the work-order that G-d presented to Moshe for the construction of the Mishkan … In Exodus 25: 8-9 Hashem tasks Moshe in this way: וְעָ֥שׂוּ לִ֖י מִקְדָּ֑שׁ וְשָׁכַנְתִּ֖י בְּתוֹכָֽם׃ כְּכֹ֗ל אֲשֶׁ֤ר אֲנִי֙ מַרְאֶ֣ה אוֹתְךָ֔ אֵ֚ת תַּבְנִ֣ית הַמִּשְׁכָּ֔ן וְאֵ֖ת תַּבְנִ֣ית כׇּל־כֵּלָ֑יו וְכֵ֖ן תַּעֲשֽׂוּ׃ And let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them. Exactly as I show you — the pattern of the Sanctuary and the pattern of all its furnishings—so shall you make it. Over the next fifteen chapters Moshe and his builders focus on building the Mishkan, its sacred furniture and accessories, and even Priestly clothing. How can we possibly apply this piece of Torah to our 21-st Century Jewish lives? I mean, really 🡪 building and using a ritual sanctuary complete with sacrificial alters and incense burning? What Jews are doing this today? Aside from a few extremists in Jerusalem who want to raise up a third Temple, no one is talking about making this stuff anymore….let alone using it. Some of you know that one Jewish approach invented by the Talmudic and later rabbis was to interpret what they read in the Torah in order to create practices parallel to many Biblical observances such as Temple sacrifices. A different relationship to this ritual was articulated by the first of the minor Prophets, Hoshea, who said in Chapter 14: 2-3

- שׁ֚וּבָה יִשְׂרָאֵ֔ל עַ֖ד יְ-הֹ-וָ-֣ה אֱלֹהֶ֑יךָ כִּ֥י כָשַׁ֖לְתָּ בַּעֲוֺנֶֽךָ׃

Return, O Israel, to the Endless One your God, For you have fallen because of your sin. קְח֤וּ עִמָּכֶם֙ דְּבָרִ֔ים וְשׁ֖וּבוּ אֶל־ יְ-הֹ-וָ-֣ה אִמְר֣וּ אֵלָ֗יו כׇּל־תִּשָּׂ֤א עָוֺן֙ וְקַח־ט֔וֹב וּֽנְשַׁלְּמָ֥ה פָרִ֖ים שְׂפָתֵֽינוּ׃ Take words with you, And return to GOD. Say: “Forgive all guilt And accept what is good; Instead of bulls we will make an offering from our lips.” The rabbis of old drew on Hoshea and simply translated much of the Temple ritual into the that fill our siddurim, our prayerbooks. So today we offer the words of our lips instead of animal sacrifice. It might be useful here to consider how the rabbis transformed the burning of bulls in an ornate Temple into our davvening out of prayerbooks the nice little shul that is Sof. One way to understand this comes from a number of contemporary philosophers and psychologists who suggest that we can differentiate between “content and process.” Content tends to remain rigidly set, as we will read in Leviticus regarding the specifics of how to offer animal sacrifices – such as where to dash the blood on the alter. The process describes the deep intention of the practices. Thus, the rabbis could echo Hoshea by telling us: “Don’t get stuck on burning bulls!” Instead, we can engage in the inner purpose of the practice. This kind of process comprises two things: First, offering up something that we can direct towards HaShem, that is our words of prayer. Second, we send these up, not with the Olah sacrifice wood-fire on a Temple alter, but with the passionate fire of our Kavvanah, our intention and attention to connect ourselves to the Source of the Universe, But how can we offer those words with the same intensity that Biblical Jews carried out the Temple worship?” One way to do this is to consider a different way to understand the beginning of G-d’s Exodus 25 “work-order.” וְעָ֥שׂוּ לִ֖י מִקְדָּ֑שׁ וְשָׁכַנְתִּ֖י בְּתוֹכָֽם׃ Rabbi Dov Ber of Meseritch, the great rebbe-master of the Chasidic movement provided a different way to translate this. Usually it reads, “And let them make Me a sanctuary that I may dwell among them” The Maggid, makes alternate usages of the Hebrew and translated it as if G-d were saying: “And let them make ME into a sanctuary that I may dwell within them.” So, in a sense, HaShem was telling Moshe and the Jewish people that after the Golden Calf incident, “When you separated from Me, I want to get closer to you so that you will know that sometimes “a cigar….ah, a golden calf is just a golden calf – its not G-d.” By imagining that I am a sanctuary within you, you can get close and remain in a deep relationship with me.” The 19th century Russian Rabbi, the Malbim, in his work Remazei Hamiskan, offered another understanding of the sanctuary. He said that it wasn’t that HaShem needed a physical Mishkan on earth, but that each one of us should turn ourselves into a sanctuary so the Divine Presence can reside in our hearts. Much of our practice as spiritual beings is to prepare or own inner Mikdash so that we may experience HaShem. When we consider G-d (or nature or Life or Love or whatever name you wish to give the unifying reality that you believe in), we can use our imaginations to either feel Her surrounding and filling us as a Sanctuary where we can take shelter or imagine ourselves as that Sanctuary that welcomes in the Divine Presence. Now, let me conclude by turning fifteen chapters later to the end of our parsha today and we can see that Moshe and his designated architects finished building the Mishkan according to G-d’s specifications. And part of Exodus 40:33 and 34 says: וַיְכַ֥ל מֹשֶׁ֖ה אֶת־הַמְּלָאכָֽה׃ וַיְכַ֥ס הֶעָנָ֖ן אֶת־אֹ֣הֶל מוֹעֵ֑ד וּכְב֣וֹד יְהֹוָ֔ה מָלֵ֖א אֶת־הַמִּשְׁכָּֽן׃ When Moses had finished the work, the cloud covered the Tent of Meeting, and the Presence of YHVH filled the Mishkan.…. What does HaShem settling into the Mishkan have to do with us? The medieval commentor Abravanel commented on this verse by saying, “As soon as the Mishkan was erected and all its furnishings put in their proper place, the cloud of HaShem immediately covered and filled the Tent of Meeting from all sides. In other words, as soon as they carefully set things up just right, then the Mishkan could become a sanctuary that will receive the Presence of the Creator. Returning to the idea of process and not just the Biblical content 🡪 Abarbanel is telling us that as soon as its builders completed their great effort and intention in constructing a meeting place for them and G-d, then the Holy One descended upon the Mishkan. So too, we can use the words and songs of the prayerbook, infusing it with our Kavvanah, our deep, spiritual intention, and as soon as we do that, immediately we can receive into our hearts the numenous, Divine Presence. This can happen today, even right now. Whether we are praying, studying Torah, serving those in need on the community or engaging in any other mitzvot. Let me end with the words of one, great Jewish soul, Leah Dineh – my mother – who used to say, “How do you know you have really been at shul service? You’ll know when you leave feeling more connected inside than you were before you entered.” Shabbat Shalom

Hateful Speech (Tazria: Lev. 12.1-13.59)

April 2024

Drash by Stan Satz

The Torah portion for this Shabbat deals with ritual purification, including leprosy, perhaps misnamed for a similar ravaging Biblical infection. Leprosy, according to myriads of rabbinical sources, is the result of hateful speech. The high priests are the ones who determine if someone has developed leprosy. “ When a man has on the skin of his body a swelling or a scab or a bright spot, and it becomes an infection of leprosy on the skin of his body, then he shall be brought to Aaron the priest or to one of his sons the priest. The priest shall look at the mark on the skin of the body, and if the hair in the infection has turned white and the infection appears to be deeper than the skin of his body, it is an infection of leprosy; when the priest has looked at him, he shall pronounce him unclean (Leviticus 13: 2-3). In an article at Torah.org, “Lessons on Leprosy,” April 23, 2020, Rabbi Yisroel Ciner depicts the three kinds of insidious leprous eruptions under the rubric tsaraat: The Hebrew words at Se’eth, Sa-pah-chat, and Ba-he-ret. “SE’ETH means to rise, to be exalted, to be elevated. It’s a form of skin disease reserved for a person who would speak against others to raise his or her own stature. SAPPAHCHAT refers to scabs adhering to persons who would not normally gossip, but if they were to join a group of evil doers, they would fit right in. BAHERET is a bright spot afflicting anyone who has spoken against another person and then tries to justify his or her behavior and exonerate themselves with rationalizations like I misremembered, I miscalculated, I inadvertently misrepresented, I misspoke, I was misquoted, I misheard, I was misled. But the truth is simple: that person missed the mark and simply lied for his or her own aggrandizement: whether it be to accumulate material gain or to offset insecurities based on the fear of ever-increasing minorities.” This is the punishment for someone developing leprous afflictions: “His clothes shall be rent, his head should be left bare, and he shall cover his upper lip; and he shall call out ‘Impure, impure.’ He should be impure as long as the disease is on him. Being impure, he shall dwell apart; his dwelling shall be outside the camp” (Chapter 13, verses 45-47). According to medieval rabbinic scholars, God (Chapter 12 in the Book of Numbers) afflicted Miriam with leprous sores because she disapproved of Moses’ marrying a Cushite woman (most likely a black Ethiopian). In fact, Miriam’s motive is to downgrade Moses so that she and Aaron can share power with him. Or as Conservative Rabbi Bradley Artson puts it, Miriam is guilty of “corrosive bigotry.” The Torah explicitly condemns hateful speech: As so many Talmudic sages have opined, “A loose tongue is like an arrow. Once it is shot, there is no holding back; “one who utters evil reports is considered in violation of the entire five books of the Torah.” In fact, leprosy is linked to the six traits that God abhors, enumerated in Proverbs chapter 6 verse 16: haughty eyes, a lying tongue, a heart hat devises wicked thoughts, feet that run eagerly toward evil, a false witness, and one who sows discord among people.” Libeling another person betrays our Judaic ethical tradition that enshrines fair play and integrity. Such negative speech is called lashon hara (literally, “an evil tongue). Lashon hara is the practice of lying about other people, rather than sincerely confronting them. It involves transforming a living, complex human being into a caricature of evil. Judged by the spiteful, hateful, falsified speech that we are bombarded with from the media, leprosy would be an appropriate punishment today. Witness our politically poisoned culture that thrives on defamation, libel, demonization, slander, denigration, gutter sniping, dehumanization, alternative facts and alternative truth, or a non-exclusive relationship to the truth. The following examples contain typically pernicious lies facilitated by the social media: Foreign-born Obama is the anti-Christ; Michelle Obama is a transsexual; Lock-her-up Hillary Clinton operated a sex slave outlet from a pizza parlor; Pres. Trump is a Russian agent and a stooge for Israel; Latin American immigrants are bloodthirsty mongrels; Medicare-for-all is a communist plot; Climate change advocates are part of an extremist left-wing cabal manipulated by George Soros, the bloodcurdling and bloodsucking Jewish guru who that wants to eradicate fossil fuels. Jews (those perennial treacherous elders of Zion) are financial bloodsuckers, fabricators of the holocaust (it’s a hoax for sure), and are the chief choreographers of the deep state as they conspire to rule the world. In all of this vicious propaganda, scurrility has replaced civility, and common decency is the casualty in the delusional, conspiratorial hate fests that proliferate on social, or should I say anti-social, even sociopathic media platforms. At the end of my teaching and administrative tenure at a community college in backwater, Bible-belt Eastern North Carolina, my immediate supervisor, a supposedly enlightened, open-minded woman whom I had always respected, uncharacteristically slandered a minority. My boss was horrified when I hired a female part-time English instructor who allegedly was gay. Didn’t I know that when the prospective instructor said she was to meet her partner after the interview, she was obviously referring to her lesbian lover? I assumed that she meant a business partner; but even if I had known that the woman was gay, I still would have hired her: she was the most qualified candidate. My boss reared back her head and huffed: “We don’t want her kind teaching here—so take care of it!” I refused to do anything at all about my treacherous faux pas. Well, it turned out that the woman a week later reneged on her contract. Had my biased boss intervened? I don’t know, and I never consulted with the viper again. I was scheduled to retire the next year. I did so with no regrets. I wouldn’t be surprised if my boss developed severe leprous outbreaks. You never know what unseemly stuff you’ll find if you scratch a bigot. But my most distressing confrontation with a slander monger occurred soon after my mother died years ago. A woman who had attended Hadassah with my mother slithered up to me at a Hanukkah party. With a conspiratorial smirk, she told me that we all knew that my mother was a difficult person whom nobody really liked. I was taken aback. Instead of verbally lashing out at this spiteful woman, or perhaps being tempted to slap her, I hurriedly left the room. But I did send her a heartfelt letter that she never responded to. Nor did I ever see her again. This is what I wrote: “Not wanting to disrupt the Chanukah party last night, I did not confront you about your disrespectful remarks regarding my recently deceased mother. Your comments were inappropriate and insensitive at best, and crude and vicious at worst. You demeaned my mother’s memory—even if what you said were true. Well, I do know that she had no use for you because you always snubbed her at Hadassah sisterhood meetings. And your vengeful comments about my mother show that she was a good judge of character. You are a disgrace to the Jewish community and to any community that values decency and respect for the dead.” At other times, I have anonymously publicized my outrage against the hateful drivel found, for example, on the AARP on-line forum, especially the inflammatory rhetoric of right-wing and left-wing extremists, people whom I have vilified as venomous toads. After a while, I realized that in my fierce rebuttals, I too had succumbed to backbiting and backstabbing, a Torah taboo. I now refrain from posting incendiary comments on any websites. The first verses of Chapter 12 in Tazria refer to male circumcision. To follow the teachings of the Torah, all of us are obligated to circumcise our hearts against smear tactics, no matter how righteously we attempt to justify our contempt. Otherwise, we might well become infected with the scales, scabs, and scum of the leprosy of the spirit. Within our Temple community, I am inspired to see so many instances in which we support and nourish, not criticize and demean one another. May our fellowship continue to flourish throughout the years! Amen.

Naso Drash

July 2024

by Daniel Koster

When I was growing up in the shtetl of Anatevka, Florida, the Rabbi used to go everywhere by bike. One day he came to me and cried, “Daniel, my bike has been stolen!” I said, “but Rabbi, you go everywhere by bike,” and he said “we know that, you just told us. I’ve got to find out who took it.” And I said “Rabbi, that’s easy. This week is Shavuot, when you will read the Ten Commandments, pause at the commandment thou shalt not steal and look at the people, and whoever acts all nervous and uncomfortable, that’s your thief.” He said, I understand, that’s what I’ll do. So come Shavuot he’s reading the commandments, and when he gets to the one about stealing, he breezes right through. So after I told him, you didn’t understand, you were supposed to pause after thou shalt not steal. And he said, “I understood fine. See, I was reading the commandments, and when I got to the commandment thou shalt not commit adultery, wouldn’t you know, I remembered where I left my bike.” Speaking of bikes, this week’s parsha deals with the transportation of the materials to build the tabernacle. Moses is charged with taking a census of the Levites to ensure there are enough people to carry the poles, sockets, and dolphins skins. Even in the desert, the practice of our faith involved a lot of people. Judaism is not about sitting alone under the Bodhi Tree, nor walking on the beach and leaving one set of footprints. If you embark on this journey, you’re going to need a minyan, and your whole family, and a board of directors apparently. The requirement for enough people has been build in from the beginning. If God didn’t want us to practice as a big community, he would have ordered a smaller tabernacle. And while carrying poles and dolphin skins may sound like menial labor, these men had to build a walled compound with an altar and holy tent on a foundation of sand to exact divine specifications, using only the tools they could carry. The Kohathites, Gershonites, and Merarites had to be strong and smart, and organized enough to accomplish this construction project every time the Israelites stopped. From then, through the Temple times, to the age of synagogues today, our practice has depended on the contributions of motivated, educated, and dependable people. And the world is full of obstacles to raising a person with these needed characteristics. As a lot of us know firsthand, everything our parents don’t do to set us up for success is work we have to do ourselves before we can contribute much to the community. All that is to say that for thousands of years, everything that matters to us as Jews has depended on parents doing a good job raising their children. After Moses assigns responsibility for building the Tabernacle, he receives instructions on the ritual of the Sotah. This is where a man who suspects his wife of adultery brings her to the tabernacle, where the priest will write down curses and scrape the ink into a mix of dust and water. If she is guilty, this water of bitterness will cause her thigh will sag and she will become infertile. If there’s one thing women hate, it’s saggy thighs. They’re always saying, does this dress make my thighs look saggy, and, did you see Becky’s thighs? She should be nominated for the SAG award. If she is not guilty, she will not be harmed, and the husband will be free of guilt. Speaking of Bitterness, everyone is quick to condemn this unconventional ritual, saying it shows how the men held all the power in that time, and I don’t suppose the women could give their husbands cursed water if they were suspected of hanging around the well a little too much. God must be a sexist, because he gave all the power to the men and left women to suffer this humiliation, whether or not they did anything wrong. Therefore are free to dismiss this whole section and figure out our own way to deal with the problem… Or… maybe God is going somewhere with this. While it’s true that this ritual does give a man the power to make his wife into “the wife who had to drink the water of bitterness,” he also makes himself “the husband who made his wife drink the water of bitterness,” and it’s not obvious that’s any better. Nobody wants to be in this situation, so my estimation is that for everyone who underwent the ritual, there were many more who did whatever it took to avoid it. The reality is that this is more than a story about how people back then dealt with their suspicions. This is a description of what will happen to you if the trust breaks down. In the desert god made the water sweet; if you and your spouse lose each other’s trust, the water in your home will become bitter. Your mind will run away, seeing everything your partner does as evidence of their vileness, proof that you should have never sacrificed your freedom for such a liar. If the partners don’t trust each other enough to work it out, small suspicion can grow into a spiky wall of spears between them. And before you assure yourself that you or your spouse would never commit adultery, remember that there are many ways to betray your partner. You can spend all the money, or neglect your part in maintaining the house, or spread bitter rumors in your community. If both parties are not carrying their tentpoles and carefully laying their dolphin skins, they are in danger of descending so deep into hell that dragging the problem before the priest seems like a good idea. By the way, this is not about me standing in judgement of anyone else, but we don’t need to get into the reasons for that right now. When bitterness flows in a house, everyone drinks it, especially the children. And when children grow up in bitterness, they do not leave the house ready to serve the community. When enough children are not ready to serve their community, the tabernacle gets built wrong, and the desert winds topples the holy of holies. That is why thou shalt not commit adultery belongs in the Ten Commandments. Just like murder and steading and false witness, adultery is enough to ruin everything. As for how to maintain a good marriage at least long enough to raise some good kids, I don’t have any answers for you. A lot of couples in this community seem to be doing great, so I’m sure to listen for any hints they can offer. I also hold onto the faith that the answers are woven into the Torah, even the strange parts. I have drunk enough bitter water in my time, and I believe God can make any concoction sweet again, as long as I know where my bicycle is.

Beha’alot’cha Drash

by Donald Armstrong and Stan Satz

July 2024 I planned to start preparing today’s drash on Beha’alot’cha last Sunday, with the goal of completing it before Shabbat on Friday evening. I did my research on Sunday, organized my thoughts on Monday, prepared an outline on Tuesday and began drafting my drash on Wednesday. Sandy said it was too bad that Stan Satz wouldn’t be able to give his drash on Becha’alotcha because of his hospitalization in the ICU. Thursday morning I had gotten no further than developing some bad puns for the opening of my drash: 1. Oh woe is no meat and only mana to eat. 2. Eat meat today and mana manana. 3. New news: blue Jews wanna eat sweet meat treats of iguana, not ohana mana Sandy gave me the look and shook her head; my anxiety was rising as my drash deadline was receding. Then, Baruch Hashem, the miracle happened. On Thursday, Stan’s wife Marie called Sandy to say that Stan had finished his drash on Becha’alotcha. Since he was still in the hospital, would someone be so kind as to deliver his drash on Shabat? I was delighted to do this mitzva for Stan, especially since I could now avoid the work and stress that would be necessary for me to create a whole drash of my own from scratch. Please note that I have edited Stan’s drash to make it shorter; however, Stan’s original, unedited drash is also available on request. Take it away Stan! Let’s get right to the meat of my drash. After schlepping in the wilderness for many years the disgruntled, grumbling Israelites demanded a better diet than the boring, bland mana that they had consumed for so long. The wailing rabble whined, “If only we had meat to eat! We remember the fish we ate in Egypt. Now we have lost our appetite on this monotonous diet of mana. Moses heard their pitiful cries. The Lord became exceedingly angry and Moses was distraught. Moses asked the Lord, “Why have you brought this trouble on your servant? What have I done to displease you that you put the burden of all these people on me? Where can I get meat in the wilderness for all these discontented people? I am alone and helpless. If this is how you are going to treat me, put me to death right now—but if I have found favor in your eyes– do not let me face my own ruin. The Lord directed Moses “Tell the people: Consecrate yourselves in preparation for tomorrow, when you will eat meat. The Lord heard you when you wailed, “If only we had meat to eat! We were better off in Egypt!” Now the Lord will give you meat and you will eat it. You will not eat it for just one day, or two days, or five, ten or twenty days, but for a whole month– until it comes out of your nostrils and you loathe it– because you have rejected the Lord who is among you and you rebelled saying, “Why did we ever leave Egypt?” But Moses said, “Here I am among six hundred thousand men on foot and you say, “I will give them meat to eat for a whole month!” The Lord answered Moses, “Is the Lord’s arm too short? You will now see whether or not what I say will come true for you.” A wind went out from the Lord and drove quail in from the sea…All that day and night and all the next day the people went out and gathered quail. They spread the quail out all around the camp. But while the meat was still between their teeth and before it could be consumed, the anger of the Lord burned against the most selfish, greedy people and he struck them with a plague at a place called Kibroth–Hattaavath, which means “the graves of the craving ones”. The Lord taught the ingrates a lesson by offering them so much quail that they gorged themselves and went belly up. On a gut level, there is a feast of wisdom for all of us in this drash: when we discount our blessings and abandon what nurtures us now for what we once craved, we get our comeuppance. We must never take our blessings for granted. Many midrashim contend that the meat the rabble rousers desired signifies all the voracious pleasures of the flesh: unbridled self indulgence, sexual promiscuity, gluttony, greed, envy, indolence and indifference or violence against those who are most vulnerable in society. Just as the malcontents’ stomachs burst from eating quail, so do our souls become emaciated by our self-absorption and our indifference to our fellow humans beings. In contrast to flesh, mana is a blessing from the Lord that nourished the children of Israel, thereby instilling within them not only trust in and loyalty to the Lord, but also the seeds of righteousness so that caring for others becomes more natural than caring only for one’s self. Moreover, the mana, which is eaten communally, reminds all of us that we should share our bounty and blessings with others. May we all appreciate and delight in how the Lord’s providence has sustained us to value our relationships with ourselves, with others and with Hashem. No matter what our circumstances, we should all recognize, appreciate and delight in all the blessings that Hashem has bestowed upon us. This Hebrew prayer, Shehecheyanu, thanks Hashem for giving us the gift of life. I pray that we will say this prayer daily and not just on holy days or special occasions. Please join me in this prayer: Baruch atah Adonai Eloheinu Melech haolam, shehecheyanu, v’kiy’manu, v’higianu laz’man hazeh. Amen and Shabat Shalom. Don Armstrong and Stan Satz

Parshah Hukkat Drash

July 2024 Drash given by David Haymer on July 13, 2024 Parshah Hukkat The name for this Parshah is often translated as “laws” or “decrees”. According to Richard Friedman’s commentary on the Torah, this Parshah can be viewed as an elaboration of the laws given at Sinai. However, Friedman also says that this Parshah might be called “transitions”, referring to the fact that it includes several major changes in our story. The first transition can be seen in how God to speaks to us to impart information. Previously, when God says: “Instruct the Israelite people…”, he speaks only to Moses. וַיְדַבֵּ֣ר יְהֹוָ֔ה אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֥ה In this Parshah, we hear in the very 1 st line (for the first time in the Tanach): God spoke to Moses and Aaron וַיְדַבֵּ֣ר יְהֹוָ֔ה אֶל־מֹשֶׁ֥ה וְאֶֽל־אַהֲרֹ֖ן לֵאמֹֽר God said: This is the ritual law that the Lord has commanded: “Instruct the Israelite people to bring you a red cow without blemish, in which there is no defect and on which no yoke has been laid. You shall give it Eleazer, the Priest to be taken out to be slaughtered…” Eleazer is, of course, Aaron’s son, and the red cow is the infamous “red heifer”. I will come back to the red heifer later, but for now the inclusion of both Aaron and Eleazer in these direct instructions presages that Moses is no longer the sole central figure in the life of the Israelites. They will have to begin the transition to other leaders. Later in this Parshah, we have another major transition of leadership occurring because of the deaths of both Miriam and Aaron. Furthermore, it is also here that we learn that Moses is told here that he will die before entering the promised land. There is a lot we might say her about the different treatments given to the deaths of both Aaron and Miriam. The death of Aaron extends over several versus, but the death of Miriam gets only one simple verse with no elaboration. Given the importance of Miriam in our history, this hardly seems fair. After all, most recently, Miriam led the singing and dancing when the Israelites successfully crossed the Red Sea without drowning, and this was the last time we saw the Israelites happy about the whole escape from Egypt. After that, we hear nothing but complaining from them about how bad conditions are. But, to go back to the idea of transitions in this Parshah, I would like to look at why God decides at this point to tell Moses about his future – meaning that he would not be allowed to enter the promised land. It all starts with – surprise, surprise, the Israelites complaining again about their conditions living in the desert – specifically about having no water. It is noteworthy to mention that their complaints are now directed to both Moses and Aaron. In response, they are both told by God to take a rod and order the rock to yield water for them and their beasts. But instead, Moses loses his cool and strikes the rock twice with the rod, and out comes copious amounts of water. Apparently, this was enough for God to say that because Moses did not trust him enough to directly follow his instructions, God would not let him enter the promised land. I think this was a setup, though, because the entire community had been told previously that no one of the generation that left Egypt would enter the land. Moses, as important as he was, was also clearly part of this cohort. And, try to imagine what would have happened if Moses had been allowed to enter the promised land – how different our history might have been! Moses might have been made into something like a deity – and this would not have been a good thing. No, the time was ripe for the Israelites to find their own way with new leadership. Anyhow, for now let’s get back to the Red Heifer. This concept of having a cow without blemish has been the source of hundreds of commentaries in our literature. Much of this controversy stems from defining exactly what “without blemish” means. If you look closely enough, you might find one white hair amongst all the red ones. Does this mean it is unacceptable? No! But, if you find two white hairs in close proximity, the cow is not acceptable. Other controversies have to do with why this cow and the ritual treatment of it is so special. It is here that our own Etz Hayim book describes a Midrash where King Solomon says: “I have labored long to understand the word of God, and have understood it all, except for the ritual of the red cow”. This of course reflects a deeper quandary as to what we are supposed to do when we read a section like this in the Tanach, including of course the rules for the laws of Kashrut. Do we try to justify following them for some health related or other reason, or do we follow the dictate: These are laws and decrees from God, and we have no right to question them (or even worry about trying to understand them)? Of course, as Jews, we tend to enjoy routinely violating this rule by endlessly discussing and debating the meaning and rationale for such passages. So, in this spirit I will offer my own perspective here on the ritual of the red cow as it relates to the general practice of animal sacrifice. First, it is widely believed that one of the great values of the Biblical emphasis on animal sacrifice was to offer it as an alternative to human sacrifice. And archeological research has shown that during Biblical times, human sacrifice was widely practiced groups in many different parts of the world. The intention of human sacrifice was, of course, to offer something of value to the “Gods” to placate them. New evidence shows that many times children, and especially twins, were used for sacrifice precisely because they were deemed to hold the greatest value in many societies. I believe this relates directly to why so much attention is paid to the red heifer. This heifer is an incredibly rare and valuable animal, and as such it is given special treatment. Other sacrifices were divided up to provide food for the Levites and the broader community, but here the entire body of the red heifer is completely burnt – its hide, flesh and blood – and its dung included, as part of the ritual. Between the rarity of this animal and the special treatment it was given was specifically intended to elevate the value of the sacrifice of the red heifer to a point where it could be used to replace the great perceived value of child sacrifice. Finally, one last element of this Parshah I find fascinating is found in 21:6 where God sends out snakes to bite people that had again been complaining too much. Moses again intercedes with God on their behalf, and God tells Moses to mount a copper snake on a standard, and anyone bitten by a snake could look at it and be cured. This, of course later became the Caduceus, the universal symbol of the medical profession as healers. But, I am bothered by the magical powers conferred to this symbol by God, as it seems to bring it dangerously close to a form of idolatry. I am bothered because we all know this is something we are supposed to avoid. For now, however, we will have to leave this as another discussion for another time. Shabbat Shalom!

Rosh Chodesh Av Drash

August 2024

by Megan Moore I would like to preface by honoring two people today. First, let me thank Alice Lachman, who went to great lengths to give me resources for the themes of the month of Av. Second, I would like to acknowledge and honor the brother of Margie Walkover, Andy Walkover, who helped make the US law that protects minors from receiving the penalty now reserved only for adult offenders. This week is his yahrtzeit. When I was first reading these two parshiyot, my eyes started to glaze over. It felt so plodding and monotonous that I could hardly focus. Perhaps that was the point. Losing Aaron, the High Priest, seems to have sucked all the drama out of the Israelites. Their burdens weigh so heavily, all they can do is robotically shuffle forward. Rosh Chodesh always takes place on a new moon, not a full one. This new beginning happens when the night is darkest. We cannot see our path ahead. The month of Tammuz, which we are now exiting, is associated with the sense of sight. Now, we are now entering the month of Av, which is associated with the ears and hearing. It is a the time to ask ourselves if we are actually listening clearly. What have we been deaf to? I know it is unorthodox, but I want to read aloud a timeless American picture book, which most of you will recognize. Perhaps some of you think children’s books are just for children– at least until you actually sit and read one as an adult. Please humor me. BOOK: Horton Hears a Who by Dr. Seuss. I had originally omitted this next part of my drash, but I had a conversation at services last night that made me feel compared to share. Sometimes, it takes the right person with the right platform to make a change in the world, like Dr. Seuss. Other times, it is just one extra voice saying a single word: Yah! Why? We say to ourselves: Why me? Why us? Why again? When we are weary, feeling small, we cannot remain in a mindset of defeat. If we believe progress is impossible, that defeat is inevitable, then we are trapped in our own echo chamber of victimhood. We as a people have a reputation for kvetching and wailing. Why us, every generation!, we always cry out. Have we stopped to listen to G-d’s reply? This picture book might sound familiar to your own family history, or perhaps how you feel right now. Sometimes it feels like we are screaming out and no one hears us. It seems absolutely futile at times. Like we don’t even matter. Dr. Seuss wrote this book as a criticism of the US government’s treatment of the Japanese and Japanese Americans during and after World War II. He was raised to hate Japanese people, and had learned that he was wrong. The nationwide criticism of Dr. Seuss for being racist and antisemitic in 2021 largely ignored his ability to change his worldview and help others do the same, even in his old age. In the darkness of a new moon, we cannot see the way ahead. In the uncertainty of a new beginning, there is infinite possibility. This month of Av, I pray HaShem opens our ears, that we listen with compassion, and we are no longer deaf to the things we ourselves need to hear. We grow together, on this little speck of dust. We are here! We are here! We are here! Let us not become accustomed to the doldrums of despair. Chodesh tov, kākou, and Shabbat shalom.

Reʻeh Drash

October 2024

by Fran Margulies

Seeing is believing! SEE!, not the usual

Shmah, “Listen! Hear! ”“Shmah Yisrael!” is our

more familiar imperative because God in our

tradition is often described as only a voice,

heard, FELT, but never seen.

Moses too wanted to see. He needed it!

Remember when a younger Moses begged

God show himself? And God accommodated by

whirling past in while Moses hunkered down

behind a rock? Moses then could indeed hear

the words, but he SAW only God’s back,

Now Moses is old; his work and his journey are

almost complete. They have all arrived on the

Eastern shore of the Jordan River. He -and

they – look across to the Promised Land, and

there they see two mountains, Gerazim and

Ebal: Gerazim, a short green mountain,

covered with ripe trees, full of fruit, watered by

the moisture from the western Mediterranean

side. Near it, across a valley, a mile away, is

Ebal, a taller but barren, very dry mountain that

is blocked by the terrain from receiving rain.

AHA!, Moses must have thought, “a visible,

teaching moment!” He COULD use the sight of

these mountains in a communal ceremony

showing God’s Blessings and Curses. And,

indeed, the spectacle might have been a

familiar custom of the time and place. I have

read that visible foundation ceremonies were

indeed used in the middle east.

And,,by the way, these ARE REAL mountains!

You too can still see them.

In out parsha today we are not shown the

dramatic ceremony at Mts Gerazim and Ebal

but later, in Ki Tavo (27:11), also in the prophet

Joshua (8:30-35,) and even more in Talmud

(Sotah 37)we get MORE details. so let’s take a

look:

(Online from R. Dovid Rosenthal) The

Levites stood between the two mountains,

carrying the ARk of the Covenant, Six tribes

stood on the lower slopes of Ebal while six

tribes stood across on Gerazim. On Ebal were

Reuben, Gad, Asher, Zebulon, Dan and

Naphtali. On Gerazim were Simeon, Levi,

Judah, Issachar, Joseph, and Benjamin.

The Levites spoke (declaimed? shouted?, and

for each CURSE, they would first turn their gaze

to the six so- called “good” tribes standing on

Gerazim and utter a negative blessing. “Blessed

is he who does NOT move back the border of

his neighbor!” They would then turn to face Mt

Ebal and repeat, shout, the same statement as

a curse. Then they would repeat both acts with

a blessing.

After each blessing and curse, both set of

tribes would say “Amen!”

The visible drama AND the participation

of the whole community -perhaps this truly

happened? – surely reinforced the reality of the

curses and blessings and strengthened their

joint sense of One People under God.

Now, as we live through our own days, it

might be fun to consider how we too might

have benefited from the dramatic clarity that our

ancestors saw and felt between God’s

blessings and curses.

Shabbat Shalom!

Debbie Friedman & Abraham

December 2024

Lech Lecha Drash by Mat Sgan

Go Forth! Genesis 12:1-17:27 Debbie Friedman

Lech L’cha (LL) to a land that I will show you

LL to a place you do not know-

LL On your journey I will bless you and you shall

be a blessing LL

LL and I shall make your name great

LL and I shall praise your name

LL to a place that I will show you

God said to Abram, Go forth from your land, from your birthplace, from your father’s house. Genesis 1 & 2 featured Adam and Noah. God must have felt great disappointment about the high points of his morality plans for humanity- He had differentiated humankind from his other creatures and creations and provided them with free will and reason. He had provided a Garden of Eden for the first man and woman. That hadn’t worked. And providing the seven Noahide laws- mostly DO Nots-had not worked either.

God regretted the humanity he had created in His image and established a different plan- He would start a subgroup within humanity with principal agents. God settled on a man and a woman, Abram & Sarai from the Ur of Chaldeans, to carry his message forward, UR of Chaldeans was well chosen in its time -it was a flourishing city; its pagan religion was thriving -idol sales were up! Huge Temples called Ziggurats about which it is said “its towers reached toward the Heavens and its foundations create aura” had been built . It was the site of pagan worship of a moon god, who was the supreme god among a pantheon of gods. They controlled the heavens & the earth as well as the fertility of crops, herbs, and families. Ur was moreover a seat of sophisticated Sumerian astronomy with star charts and all. The gods seemed to be looking in favor on UR.

As physicist-Rabbi Jeremy England writes-God’s action initiated a unique form of religious particularism. As we recite in our Alenu Congregational prayer- God made our lot unlike other people and assigned to us a unique destiny. Our task, however, was and is not particular-it was and is universal- to bring moral guidance to all humanity. Abram was chosen to initiate a movement that would struggle to introduce and perpetuate Ethical Monotheism in human affairs.

Biblical writing & mishnaic mythology indicate that Abram had doubts about the moon god & the pantheon of gods. In a midrash-Genesis Rabbah chapter 38- Abram is said to have smashed their idols. When challenged by his father Terah, an idol maker, Abram proclaims that the idols attacked each other. Terah responds that that explanation is ridiculous since idols have neither soul nor spirit. Abram makes his point by asking -why do we worship idols who can’t do anything?

We do not need to accept this mythology as proof of anything to appreciate its wisdom in illustrating how change occurs in human affairs and describing it as based on the most compelling evidence and inspirational sources of the times with the highest possible motive. It asserted the idea that life has meaning and that humanity was created and Judaism was chosen to understand and further the best aspects of it for all for eternity. Consider the role of the Jewish people historically and culturally since then.

Just as Noah was a good man “in his time.” Abram was a good man in his time and setting. Abram sought to find a good life through reason, experience, spiritual pursuit, and understanding. Abram realized that there is one God. It is not the supposed moon God. Rather it is one who demands righteous behavior, unconventional thinking, and human kindness, God decided that Abram of UR had the attitude and background to be capable of knowing and loving Hashem and leading a nation on God’s behalf.

God proposed a covenant with Abram. The covenant contained obligations & responsibilities; expectations & rewards- both ways. Holy Land, numerous heirs and adherents, behavioral guidelines, and eternal recognition would be God’s gifts to Abram. Loyalty, devoted generations, male circumcision, an eagerness to learn and be creative, & a willingness to help keep the world in good repair would be Abram’s gifts to God.

God said to Abram , in so many words, up-grade and complete your way of life by being my agent. Sarai and you will have name changes to highlight your change of status. Henceforth you will be called Abraham and Sarah.

It is said that Abraham faced ten tests after his selection and agreement. Most of the tests are found in this sedrah. They range from going forth from his country, his kindred, and his father’s house to later on being told to sacrifice his beloved son Isaac. Abraham met his tests with guile, deception, force, loyalty, and determination. Now Jews are tested yet again by an implacable enemy that wants to destroy them. Who will be our Abrahams and Sarahs?