Moses and Monotheism

Moses Was Not a Monotheist

by Robert J Littman, M.Litt., Ph.D.

Sigmund Freud wrote a work Moses and Monotheism in which he posited that Judaism got its monotheism from Moses, who was an Egyptian, a priest of Akhenaten, who fled Egypt after the death of the pharaoh. He saw Moses as the founder of monotheistic Judaism. Freud was wrong on almost all counts. Archaeology and increased understanding of Egypt and Near Eastern cultures in the almost 100 years since Freud’s book, show how wrong he was. Since the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948, there have been over 250 archaeological excavations and over 4000 salvage excavations. This has transformed our knowledge of the origins of ancient Israel. We now know that the Israelites did not coalesce as a distinct ethnic group until the middle of the 13th century BCE, 100 years after Akhenaten lived. Akhenaten was the first true monotheist. He rejected the worship of the Egyptian pantheon and elevated the sun god Aten to the position of the sole god of the universe. After his death, the priests of Amun reestablished the polytheistic religion of Egypt with Amun-Ra at its head. The name of Akhenaten, his images and his existence were stamped out. He, and his successor Tutankhamun, do not even appear in the official lists of pharaohs, kept by the ancient Egyptians. While Akhenaten was a true monotheist, Moses and early Judaism were not monotheistic. Rather early Judaism from the time of Moses In the 13th century BCE to the end of the first Temple in the late 7th century was henotheistic, that is the worship of one god without denying the existence of other gods. This early Judaism was aniconic-it forbade any images of God. The Ten Commandments, given to Moses by God on Mount Sinai are clearly henotheistic. The commandment says, “You shall have no other gods “before my face” which means “in preference to me.” It is not like the watch cry of Islam, “There is no God but Allah”

لَا إِلَٰهَ إِلَّا ٱللَّٰهُ |

When Moses crosses the Sea of Reeds and sings the Song at the Sea, in praise of YHVH, he sings, “who is like you among the gods”, which clearly indicates that there were other gods, none as great as YHVH. When we turn to the prophets, during the Kingdom of Israel, we find polytheism abounds. Saul’s son who ruled for two years after the death of his father, bears the name of Ishbaal, or “man of Baal,” which suggests the worship of Baal alongside that of YHVH. The prophets name bad kings and good kings. The bad kings had temple prostitution, worship of Asherah, idols in the temple, compared with the good kings. After the split into the Northern Kingdom of Israel and Kingdom of Judea, all the rulers of the Northern Kingdom are called “bad kings.” Very few made the grade as “good kings,” which include Hezekiah and Josiah. At least two thirds of the First Temple period had “bad kings.”

The Shma has become the credo for Jews and has been interpreted as the watch cry of monotheism. This prayer appears only in Deuteronomy. This last book of the Pentateuch is a revision of the account of Moses, and is most likely the “the book of the Law” discovered in the Temple of Jerusalem about 622 BCE (2 Kings 22:8; 2 Chronicles 34:15). Hezekiah rid the Temple of idols and reinstituted the sole worship of YHVH, only to have his reforms reversed by his son Manassah (687-643 BCE), who restored polytheistic worship of Baal and Asherah (2 Kings 21) in the Temple. Josiah (640–609 BCE) took after his grandfather Hezekaiah, and removed the worship of other gods. He validated his reforms through the book of Deuteronomy. The central [something missing] to Deuteronomy is the shma.

שְׁמַע יִשְׂרָאֵל יְהוָה אֱלֹהֵינוּ יְהוָה אֶחָד׃.

In subsequent centuries the Shma has been translated in a way to reflect monotheism. But if we look at its historical context the translation becomes clearer. The key to understanding is the word אֶחָד. Given the motive of eliminating idols and polytheism, the translation should be “Hear (and obey), Israel, YHVH is our God, YHVH alone.”

It was not until the 5th century BCE that Judaism becomes truly monotheistic. A main influence of this monotheistic trend may have been Zoroastrianism, which, though not monotheistic, has monotheistic tendencies. We find in the writing of Deutero-Isaiah the first clear statement of YHVH as the only god who exists:

ישעיה מד:ו כֹּה אָמַר יְ־הוָה מֶלֶךְ יִשְׂרָאֵל וְגֹאֲלוֹ יְ־הוָה צְבָאוֹת אֲנִי רִאשׁוֹן וַאֲנִי אַחֲרוֹן וּמִבַּלְעָדַי אֵין אֱלֹהִים.

Isa 44:6 Thus said YHWH, the King of Israel, their Redeemer, YHWH of Hosts: I am the first and I am the last, and there is no god but Me.

ישעיה מה:ה אֲנִי יְ־הוָה וְאֵין עוֹד זוּלָתִי אֵין אֱלֹהִים…

Isa 45:5 I am YHWH and there is none else; beside Me, there is no god…

As Judaism became monotheistic, אֶחָד came to be translated “one” to reflect the development of monotheism. Moses was not a monotheist, but he was the inventor of Judaism. When Judaism became monotheistic, Moses received the title of the inventor of monotheism.

Some Other Thoughts on Moses

- The Name of Moses

Moses may not have been a priest of the pharaoh Akhenaten, but he was a Jewish Egyptian and brought Egyptian religion and culture with him to found the Jewish nation. Today, an American Jew will have his Judaism, but often bear an American name, dress like an American, think like an American and talk like an American. The same could be said for the French Jew, the British Jew, the Italian Jew. Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan argued that all Jews living outside of Israel lived in two civilization, a Jewish one and the civilization where they were born. American Jews bear American names, Italian Jews Italian names. So Moses had an Egyptian name. Exodus (2:10) relates that Moses was named by Pharaoh’s daughter after a Hebrew verb that means “draw out” since she drew him from the Nile. Even the medieval Jewish commentators, such as Ibn Ezra and Hezekiah ben Manoah were puzzled how an Egyptian princess could know Hebrew. Hezekiah ben Manoa suggested that the princess either converted to Judaism or had the name suggested by Moses’ mother Jochebed. The attempt to identify Moses’ name is a folk etymology, based on similarity of sounds rather than reality. In fact, Moses is a typical Egyptian name, often of Pharaohs or royalty. It means “is born,” from the Egyptian word ‘mese’, and was a very common theophoric element in pharaonic names. For example, Rameses (Ra is born), or Thothmose (Thoth is born). Ramses in one inscription is called simply “Mose”.

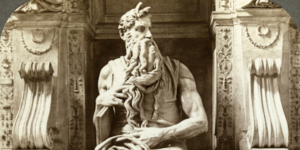

- Moses has horns?

Many of us have seen the famous statue of Moses in the Basilica of San Pietro in Vincoli in Rome, by Michelangelo. Moses is depicted with horns. When Moses comes down from Mount Sinai in Exodus, he is described as “qaran” which can mean “rays of light” or horns. Most translations have interpreted “qaran” as rays of light. However, the Latin translation in St. Jerome, is cornu, which can mean either rays of light or horns. Starting in the 11th century CE Moses is depicted with horns, and that continues until the early 16th century, when “cornu” started to be translated as “rays of light.” But did the original Hebrew text preserve the picture of Moses with horns? At the time of Moses, Israel and the Levant had been under Egyptian influence for hundreds of years. For much of the second millennium the Levant had been Egyptian territory or an Egyptian vassal state. Egyptian border fortresses, dozens of Egyptian scarabs and material remains have been found in archaeological excavations in Israel. The events at Mount Sinai are full of Egyptian material. If we examine the 10 Commandments, 6 are present in the Confession of Righteousness of the Egyptian Book of the Dead. The Golden calf is probably the Apis bull of Egypt. So who has horns in Egypt? The god Amun Ra. When Alexander the Great conquered Egypt in the 4th century BCE, he was depicted with the horns of Amun Ra. So perhaps Michelangelo was right-Moses was wearing horns when he descended from Mount Sinai.