The Blessings of Yaʻakov

Toldot Drash By Alexander Fellman

There’s a story I like. A Jew was found on a deserted island. He’d made quite a time of his prison there, building himself a house, a street, and two synagogues. “I go to that shul every day to pray,” he said, pointing at one. “When do you use the other?” His rescuers asked. “That one? I wouldn’t be caught dead in that shul!”

We are a people who love to argue. And most of the time, who we love to argue with is each other. But at the end of the day, we are all part of one big messed up family. A Jew is a Jew.

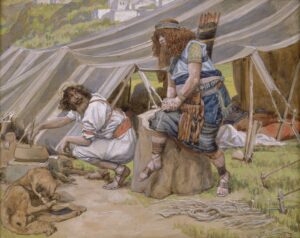

x1952-110, The Mess of Pottage, Artist: Tissot, Photographer: John Parnell, Photo © The Jewish Museum, New York

And Esau, for all his faults, is a Jew. Now, hold on. What do I mean by calling him, of all people, a Jew? Just that. He was born the legitimate son of Yitzhak Avinu and Rivka Imeinu, and unlike Yitzhak’s brothers there was never a question of his place in our company until centuries after his death. A good Jew? Nu, but still a Jew. The sages say that he sits in Gan Eden with his brother, father and grandfather, even if there’s some dispute on what becomes of him later. Ishmael, and Keturah’s sons, have never been so counted.

Two weeks ago, in Parsha Toldot, we watched our ancestor Yakov steal his brother’s blessings, having already stolen his birthright. He was, we are told, unworthy of them. And so he was. He is the prototype for many Jews in our history given the opportunity for greatness who have it stripped from them for their sins. That we don’t know the details of Esau’s sins does not mean that they were not the equal in depravity of Saul Hamelech or the kings in the north. But we don’t deny their Judaism, as much as we’d like to. So, Jew he is, and sinner he was, and cast out he was, and remained, and when it was all over and done with Yitzhak Avinu didn’t seem too heartbroken, did he? He blesses Yakov with all that is good, and tells Esau that at some point he will be freed from his second place. But not to take back his birthright, simply to stand besides his brother. And so it will be, and so it was.

In this week’s Parsha, we see that Yakov takes possession of his father’s property as the heir, with Esau taking only what he had earned of his own. Yakov then takes ownership of the land of their fathers, while Esau goes across the river to the lands that would be home to his descendants, the land of Edom. At the end, the list of Esau’s descendants are given, and the sages often draw attention to the presence in their midst of Amalek. Amalek is singled out because, unlike most of the rest of our kin, his descendants attack our people on their way to the land of Canaan out of sheer spite. And for this they were cursed. But they began cursed, too. They are excluded, at the end of this parsha, from the tribes of Edom, the legitimate descendants of Esau.

What our sages don’t often do is talk about what happened to the rest of the Edomites. There’s a very interesting answer to that, and it isn’t what the sages say. Esau was no more the ancestor of the Romans, save in the most metaphorical of ways, than he was the ancestor of the Chinese. We know who the Edomites were then, and we know who they are now. Look around you. To the left, to the right; We are the Edomites, as we are Israelites. Indeed, the last Kings of Judea were descended as much from Esau as from Yakov. How is this?

The lands across the river from Israel, or in the south, the modern Negev, have never been pleasant or comfortable. It’s a hard living there, and the Edomites found it growing more and more intolerable as time went on and the climate grew worse. Their cousins, our cousins, the Ishmaelites, were more hardened to the desert and gradually began to move up, and the Edomites began to return to their ancestral home. There was space for them; As the kings of Judah fought war after war with Assyria and Babylon and Egypt, the lands in the south around Beersheva grew depopulated. Nature, and people, abhor a vacuum. The people of Judah moved out, willingly or not, and the Edomites moved in, willingly or not.

When the Prophet and our people returned from the Babylonian captivity, they reestablished themselves around Jerusalem. Our cousins were left to their own places in the south and their own business, while we concentrated on rebuilding the temple. There was peace in the land. Except for all the times there wasn’t, and they largely kept themselves out of that, despite our prophets occasionally slandering them with the crimes of others. They even tried their best to keep out of our struggles with the Greeks. We all know how that ended for us, eventually. If you don’t, the coming holiday is a good time for you to learn. We never talk about how it ended for them.

It isn’t what I, or our sages, call our finest hour. As I say, we don’t talk about it. But it took longer to drive the Greeks out than we tend to talk about, and they weren’t so much driven out as they decided to cut their losses, and one of the consequences of them doing so was that suddenly for the first time in centuries Jews ruled much of Judea. Including the part where the Edomites were busy keeping to themselves and worshiping their, or our, God in their own way.

For the first, and so far as I know only, time in our history a leader of the Jews decided that this would not do. Yohannan the High Priest, known to history as John Hyrcanus, marched south and gave the Edomites, or the Idumeans as the Romans and Greeks called them, an option. They could convert, or they could leave, or they could die. They chose to convert. And as converts, a Jew is a Jew. With the exception of the children of Amalek, who had always been marked out as apart even from their kin, the descendants of Esau returned to the faith of their fathers. Don’t ask me what happened to the Amalekites; we lost track. But the rest of them joined Israel. Or, rather, rejoined.

Fittingly for the season, Herod the Great, Herod the Idumean, was one of their descendants. Whatever our sages thought of him at the time and since, he always considered himself both a Jewish King and King of the Jews. And we’re happy enough with him when it suits us. Indeed, all the surviving remnants of the Second Temple, including the Kotel, the western wall, were built by his men under the direction of his priests. That’s the mark of a Jewish leader, by my reckoning. That we, his co-religionists, can curse his name and bless it at the same time.

And it was his line, mingled with the Hasmoneans, that contained the last Jews to rule over the land of Israel until 1949. And when we went on our last exile, they came with us; and when we returned, so did they. Brothers by brothers. And as no one knows the tribes beyond Levi, none know a convert as anything besides a Jew.

Yitzhak’s blessings, then, were fulfilled. And may it be Hashem’s will that as our people lived to see the blessings of Yitzhak come true, that we live to see the blessings of Yakov Avinu come true and the exiles be gathered, and those of Avraham Avinu, and there be peace between us and all our kin, and we be numbered as the stars in the sky, and of the prophet: That nation shall not lift up sword against nation, and neither shall they learn war anymore.

Good Shabbos.